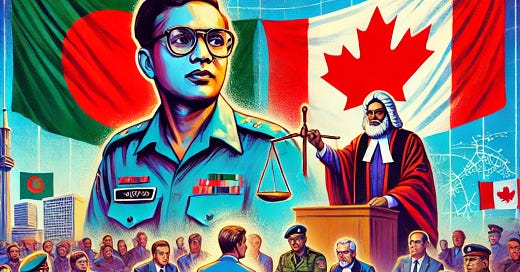

Why Canada Refuses to Extradite Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's Convicted Killer Despite Repeated Requests from Bangladesh

A Case Study of Bangladesh to Understand India's 26 Pending Extradition Requests to Canada: Navigating Legal Complexities.

India's Extradition Requests to Canada: A Complex Legal Landscape

India has raised alarm over 26 long-pending extradition requests with Canada, some languishing for over a decade without resolution. At the centre of this diplomatic friction are high-profile cases involving notorious criminals like members of the Lawrence Bishnoi gang, wanted for terror-related activities. On Thursday, Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal revealed that despite providing Canada with extensive security-related information and multiple requests for arrests, little action has been taken by Canadian authorities. The situation has intensified tensions between the two nations, with India pointing out that some of these very individuals are now implicated in crimes on Canadian soil.

Convicted Assassin of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is in Canada

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Bangladesh's founding father, was assassinated in a military coup on August 15, 1975, barely three years after the liberation of the nascent country. Among the key perpetrators was Noor Chowdhury, a former Bangladesh Army major, who directly participated in the killing of Sheikh Mujib and his family. After being convicted in absentia and sentenced to death by a Dhaka court in 1998, Chowdhury fled to Canada in 1996, where he has lived ever since. Despite the Bangladesh government’s repeated requests for his extradition, Canada has refused, citing its legal prohibition against extraditing individuals to countries where they face the death penalty.

Canada's Legal Stand: A Barrier to Extradition

Canada’s refusal to extradite Noor Chowdhury, grounded in its abolition of the death penalty and commitment to human rights, offers a case study that parallels India’s frustrations over its 26 pending extradition requests. While the crimes of figures like members of the Lawrence Bishnoi gang may differ in nature, the legal principles blocking extradition are consistent. Canada's unwavering stance on non-refoulement and the death penalty has become a major obstacle, not just for Bangladesh, but also for India, underscoring the broader legal complexities involved in extradition between the two nations.

Canada’s Stringent Extradition Laws

While India's frustration with the stalled extraditions is understandable, it is crucial to acknowledge that Canada's extradition process is tightly bound by its Constitution and a firm commitment to human rights. Extradition requests are subject to meticulous legal scrutiny, ensuring that all actions align with both domestic legal frameworks and international obligations. These stringent safeguards mean that Canada's approach to such matters is less about diplomatic relations and more about adhering to fundamental legal principles.

The Death Penalty Factor

One of the most significant hurdles in securing extradition from Canada is the issue of capital punishment. Canada abolished the death penalty in 1998 and has since maintained a strict policy of not extraditing individuals to countries where they might face execution. Bangladesh’s ongoing struggle to extradite Noor Chowdhury serves as a clear example. Despite being convicted of a heinous crime—the assassination of a national leader—Chowdhury has remained in Canada, protected by the Canadian legal system’s refusal to allow his return to face potential execution. This same policy applies to India and poses a considerable challenge to its pending requests.

Principle of Non-Refoulement

Another legal principle playing a key role in Canada’s approach is non-refoulement. This international human rights doctrine prohibits the extradition of individuals to countries where they may face torture, inhumane treatment, or punishment that is deemed cruel or degrading. In cases like Noor Chowdhury's, Canada has invoked this principle to justify its refusal to extradite, highlighting its prioritisation of human rights even in the face of serious criminal charges. This doctrine applies equally to India’s extradition requests, particularly where there may be concerns about the treatment of the individuals upon their return.

Applying the Law Equally

Canada’s refusal to extradite is not targeted specifically at India. Rather, its legal standards apply equally to all nations, regardless of the severity of the crimes or the requesting country's diplomatic status. Whether the case involves individuals accused of terrorism, as with India’s requests concerning the Lawrence Bishnoi gang, or a high-profile political assassination, such as Chowdhury’s, Canada’s legal system applies the same principles across the board. This uniform approach underscores the independence of Canada’s judiciary and its adherence to constitutional obligations.

Comparative Severity of Crimes

Although the alleged crimes committed by members of the Lawrence Bishnoi gang, including terrorism and organised crime, are serious, they do not necessarily surpass the gravity of crimes like the assassination of a national leader. Yet, both types of cases are treated with the same level of legal scrutiny in Canada, reflecting the country’s commitment to equality before the law. For India, this means that providing sufficient evidence and meeting Canada's stringent legal standards will be critical in moving forward with its extradition requests.

The Path Forward

For India to make progress on its 26 pending extradition requests, several key steps must be considered:

Providing Robust Evidence: India must ensure that the evidence submitted meets Canadian legal standards, particularly in cases involving high-profile criminals like the Lawrence Bishnoi gang.

Adherence to Dual Criminality: Extradition in Canada is only granted if the crime in question is considered an offence under both Indian and Canadian law. This dual criminality requirement means that the charges must align with Canadian legal definitions.

Guarantees Against Capital Punishment: One of the most significant challenges is addressing Canada’s prohibition on the death penalty. India may need to offer guarantees that the individuals in question will not face execution or other punishments that violate Canada’s legal and human rights principles.

The Diplomatic Fallout and India’s Domestic Response

India’s recent reaction to the pending extradition requests comes amidst rapidly deteriorating diplomatic relations between Canada and India. These tensions have been further strained by Canada’s allegations that Indian intelligence was involved in the assassination of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Canadian citizen and Khalistan ideologue, in Vancouver last June. Nijjar, a designated terrorist under Indian law, was at the centre of tensions, and the diplomatic row that eventually led to the expulsion or withdrawal of the High Commissioners from both countries1. India’s call for action on these pending extraditions could be seen by some as addressing domestic audiences, aiming to highlight perceived double standards in Canada’s approach to terrorism and extradition.

Navigating Legal Complexities in a Strained Diplomatic Environment

While India’s frustration is understandable, especially in the context of the current diplomatic fallout, it is essential to view these extradition challenges through the lens of Canada’s legal obligations. Bangladesh's unsuccessful attempts to extradite ex-Major Noor Chowdhury illustrate that Canada’s stance is consistently rooted in its commitment to human rights, particularly its opposition to the death penalty. For India to make meaningful progress, it must align its diplomatic strategy with these legal realities, adapting its approach to address the complexities of Canada’s legal framework. Rather than viewing the delays as deliberate non-cooperation, a more nuanced understanding of the legal barriers could foster more productive engagement. Even as we stand firmly with the Modi Government's diplomatic manoeuvres, whether in relation to Canada or analogous issues with the United States, it is vital to navigate these challenges with a balanced strategy that respects the legal frameworks of all parties involved2.

Updated Endnote

India’s stance on extradition requests from Canada and the USA reflects a nuanced approach that appears to prioritise specific diplomatic relationships over a consistent principle-based policy. According to official statements, 27 extradition requests have been made to Canada, with 26 of these returned to India for further evidence, and only one case currently under consideration. Although Indian media frequently portrays all 27 cases as linked to pro-Khalistan elements, only five of them are reportedly connected to such individuals.

In contrast, India has made 60 extradition requests to the USA, none of which are currently under consideration. Despite the similar positions taken by both Canada and the USA regarding extradition, public and official discourse tends to focus more on Canada, suggesting that India’s responses are influenced more by diplomatic priorities than by a uniform application of principles.

Breaking News: Canada Officially Labels Indian High Commissioner 'Person of Interest' in Hardeep Nijjar Killing

Canada Officially Describes Indian High Commissioner 'Person of Interest' in Hardeep Nijjar Killing

Unexpected Legal Setback Amid India-US Diplomatic Efforts

US Justice Department Announces Charges Against Former RAW Agent