The Stark Divide: Corporate Debt vs. Farmer Loans in India

Farmers' Loans Recovered as Arrears of Land Revenue; Corporate Debt Written Off Under the Guise of 'Debt Resolution'.

Corporate Debt vs. Farmer Loans in India

India’s financial system reveals a profound and troubling divide when it comes to handling debt. Small farmers, already grappling with challenging conditions, face brutal debt recovery mechanisms, while large corporations and their promoters enjoy leniency and evasion of personal accountability, much less culpability. This disparity not only worsens inequality but reflects a broader, systemic flaw: a structure that privatises profits for the wealthy and socialises their losses onto the state and the taxpayer. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), which was designed to streamline corporate debt resolution, has instead become a vehicle for large corporations to shed debt while leaving public institutions to bear the brunt of the financial damage. This is not just a policy failure; it is a gross injustice that protects the rich and powerful while crushing the most vulnerable, at the bottom of the massive socio-economic pyramid.

The Plight of Small Farmers: Trapped in a Rigged System

Small farmers in India are consistently weighed down by crushing debt with little recourse. While corporate defaulters are allowed to renegotiate massive loans and walk away from defaults with minimal personal consequences, small farmers are offered no such luxuries. Instead, the state's recovery mechanisms are ruthless and unforgiving.

a.) Recovery as Arrears of Land Revenue

For farmers, a loan default is treated on par with failure to pay land revenue. Government agencies step in with the full weight of the law, seizing whatever assets they can, regardless of the devastating consequences on the farmer’s family and community.

b.) Imprisonment for Up to 40 Days

An archaic law allows for the imprisonment of farmers for up to 40 days for defaulting on agricultural loans. This brutal punishment, which serves no purpose other than furthering their misery, exemplifies a justice system that punishes the poorest and the weakest for economic hardships.

c.) Attachment and Sale of Movable Property

Farmers stand to lose crucial assets such as crops—both harvested and standing—farming equipment, and livestock, all of which are vital for their survival. These forced seizures not only strip them of their livelihood but also make it nearly impossible to escape the relentless grip of compounding interest rates, plunging them deeper into an unending cycle of debt and poverty.

d.) Forced Sale of Immovable Property

The ultimate tragedy for a farmer is the forced auctioning of their land. Land, often their only source of income and pride, is stripped away, leaving families destitute and without a future.

Debt-Relief to Farmers: Smaller than Projected; Impact Limited

While the government has introduced multiple farm loan waivers over the past decade, these measures, modest in relation to the size of the agricultural economy, have proven to be mere temporary fixes. Between 2017 and 2022, several state governments, including Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Punjab, rolled out relatively “large-scale” loan waiver schemes amounting to tens of thousands of crores. For instance, Uttar Pradesh launched a Rs 36,359 crore loan waiver in 2017, while Punjab implemented a scheme offering up to Rs 2 lakh in relief for small and marginal farmers. However, many farmers, despite being eligible, have voiced their frustration over not receiving the promised debt relief, particularly in cases involving loans from cooperative societies, where governance mechanisms are notoriously weak.

Furthermore, none of these state government schemes have addressed the exploitative loans advanced by moneylenders, often disguised as friendly commission agents (known as artiyas) in the mandis. These informal loans, frequently given at usurious rates, continue to weigh heavily on farmers. Despite the waivers, the core issues driving agrarian distress—such as low crop prices, market volatility, and rising input costs—remain unaddressed. As a result, loan waivers provide only fleeting relief, with both the financial and psychological benefits being limited.

Adding to this, the media narrative has consistently portrayed farmers, particularly those agitating for remunerative Minimum Support Prices (MSP), as if they are attempting to extort scarce government resources. This distorted portrayal diverts attention from the real structural problems, while casting farmers' legitimate demands in an unfair light.

The Real Problem: Structural Issues in Indian Agriculture

a.) Statutory MSP: A Vital Lifeline for Farmers

The agricultural debt crisis in India stems not only from the loans themselves but from the structural challenges that farmers face. Unpredictable weather patterns, poor market access, volatile crop prices, and limited access to modern farming techniques have trapped farmers in a cycle of perpetual debt. While state governments frequently resort to loan waivers as a politically expedient measure, these initiatives fail to address the root causes of agrarian distress. What is truly needed is comprehensive agricultural reform focused on sustainable farming practices, improved market infrastructure, and better access to finance, including statutory Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for all major crops across the country.

b.) Procurement Budget: Essential for National Food Security, Not a Burden

It is crucial to recognise that the procurement budget, often reflected as an expense, plays a vital role in the nation’s statutory food security programme. The Food Corporation of India (FCI) procures produce at a reasonable price to sustain this backbone, which, as the Prime Minister rightly boasts, provides free rations to nearly 80 crore Indian citizens. The costs related to procurement, including operational expenses, pilferage, interest costs, transportation, and storage, along with administrative expenses incurred by central and state agencies, should not be seen as a "dole" or "favour" to farmers, as often projected when figures on "food" and "fertiliser" subsidies are made public.

c.) Fertiliser Subsidies; Export Restrictions: Misconceptions and Real Beneficiaries

Similarly, the fertiliser subsidy, although portrayed as benefiting farmers, primarily goes to manufacturers, including government-controlled entities like NFL and IFFCO. In fact, the government could easily import fertilisers at cheaper rates from international markets. Additionally, sudden and unilateral controls on commodity exports directly harm farmers by passing on real—not just notional—losses to them. Recent examples include export restrictions on rice and the imposition of Minimum Export Prices (MEP) on basmati, both of which have inflicted significant financial damage on farmers.

These issues highlight the need for a more balanced approach that supports farmers without distorting the narrative surrounding subsidies and procurement1.

Corporate Debt: A Universe of Privilege and Protection

While farmers are subjected to a harsh and unforgiving debt regime, corporate debt defaulters receive alarmingly lenient treatment. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), introduced in 2016 to streamline corporate debt restructuring, has evolved into a tool that allows large corporations to evade responsibility, shifting the massive financial burden onto creditors—predominantly public sector banks. The staggering "haircuts" that banks are forced to accept are legitimised through an ostensibly independent, quasi-judicial process under a central law, which ironically makes banks more comfortable conceding these enormous losses than they were under the earlier RBI-mandated bilateral debt rescheduling mechanisms. This legal veneer provides a semblance of due process, while in reality facilitating disproportionately favourable outcomes for corporate defaulters.

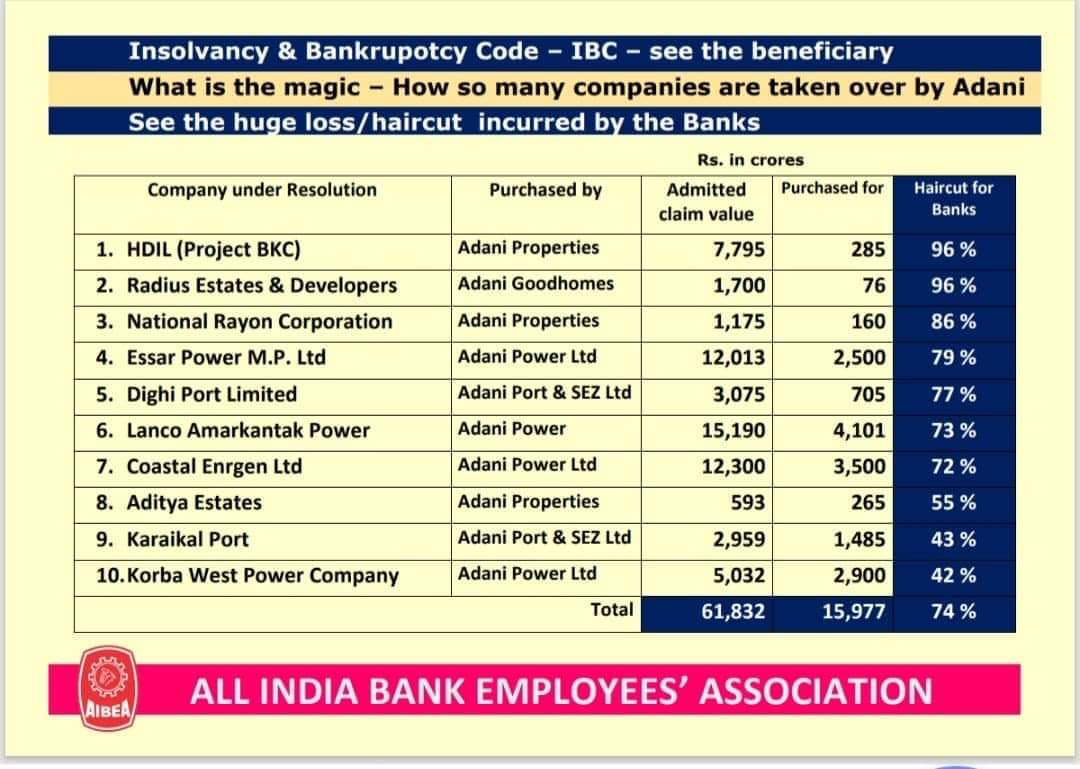

Massive Haircuts for Corporations

The scale of corporate debt write-offs through the IBC is staggering. According to the All India Bank Employees Association, since its inception, the IBC has facilitated the rescue of 517 companies while also enabling the closure of several unviable ones. However, these resolutions have come at a steep cost to creditors, particularly public sector banks. The practice of "haircuts"—where creditors agree to settle for a fraction of the original debt—has become a widespread feature of these corporate deals.

For example:

Adani Group acquired companies worth Rs 15,977 crore, resulting in banks accepting haircuts ranging from 42% to an incredible 96%.

Radius Estates and Developer saw assets worth Rs 1,700 crore sold to Adani Goodhomes for just Rs 76 crore, resulting in a staggering 96% loss for creditors.

Adani Properties purchased HDIL’s Virar project for Rs 285 crore against a claim of Rs 7,795 crore, once again reflecting a 96% haircut for creditors.

Scale of Corporate Debt Write-offs

Recent reports from bank employee associations reveal that the IBC has resulted in increasingly larger write-offs for corporate debt. In the first quarter of the 2023 fiscal year, banks experienced an average haircut of 68%, highlighting the growing scale of corporate debt waivers. While the IBC has played a role in resolving distressed assets, the enormous concessions granted to large corporations raise serious concerns about fairness and the burden on public financial institutions.

Sovereign Dues and the Erosion of Accountability

One of the most troubling aspects of corporate debt resolution is the way it allows companies to evade their tax obligations. In a landmark ruling, the Supreme Court of India, in the Ghanashyam Mishra & Sons Pvt. Ltd. vs. Edelweiss Asset Reconstruction Company Ltd. case, held that government dues, including statutory taxes, are extinguished if they are not included in the resolution plan approved under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). This ruling effectively creates a legal loophole, allowing corporations to default on taxes owed to the government, further entrenching the privilege enjoyed by corporate defaulters in an already skewed system. Meanwhile, the same government relentlessly pursues small farmers for minor arrears, showcasing the stark double standards in the enforcement of debt obligations.

Employee Dues No Longer Protected 100%

Even employee dues are not fully protected under current laws, leaving workers vulnerable in corporate insolvency proceedings. Many corporations not only fail to deposit their own share of contributions to Provident Fund (CPF) or Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), but also misappropriate the employees' own share, which they deduct from salaries but never deposit. This glaring omission in the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) leaves employees as helpless spectators while the Committee of Creditors (CoC) deliberates. Even when new promoters take over the company, they may promise to settle employee dues, but often pay in instalments, with no guarantee that the full amount will ever be cleared. This perpetuates a cycle where wage and retirement arrears continue to pile up, leaving employees effectively held hostage by the new owners or management, who can continue to default on these obligations without meaningful legal recourse for the workers. In essence, the very people who built the company are left at the mercy of new management, with their financial security hanging in the balance.

Media Silence and Public Perception: Skewing the Narrative

Mainstream media, particularly business news outlets, often downplay or ignore the scale of corporate debt write-offs, while highlighting farm loan waivers as burdensome and irresponsible. This skewed narrative suggests that relief for farmers is a drain on the economy, while corporate debt restructuring is framed as necessary for economic stability. The media's silence on the larger corporate haircuts and debt waivers perpetuates a false narrative that unjustly blames farmers for India’s financial woes while shielding large corporations from even the most cursory scrutiny.

The Way Forward: Reforming India's Debt Resolution Framework

India’s debt resolution framework requires an urgent overhaul to address the glaring inequalities between how corporate and farmer debts are treated. The current system has created a two-tiered system where:

Small farmers face severe consequences, including asset seizures and imprisonment, for relatively minor defaults.

Corporate promoters walk away with valuable assets after shedding massive debt burdens, leaving public financial institutions to absorb the losses.

To rectify this injustice, several key reforms are needed:

Stricter Accountability for Corporate Promoters: Corporate promoters must be held personally accountable for financial mismanagement. Loopholes that allow them to siphon off funds and hide behind the corporate veil must be closed.

Ending the Privatisation of Corporate Profits and Socialisation of Losses: Public institutions should no longer bear the brunt of corporate failures. The practice of allowing corporations to benefit from public funds while offloading losses onto the state must end. Stronger oversight and transparency in corporate debt restructuring processes are essential.

Reform of Media and Public Perception: Academic institutions and independent think tanks must expose the media's double standards, bringing attention to the vast sums written off for large corporations under the IBC, while farmers continue to be vilified for much smaller waivers.

Addressing the structural issues of the farmer markets and statutory MSP.

In Summary

a.) A Skewed Debt Resolution Framework

India’s current debt resolution mechanisms disproportionately favour the wealthy, often at the expense of the public and small farmers. It is time to establish a more equitable system that holds corporate promoters accountable and protects public resources. Addressing these structural imbalances is essential for India to build a fairer financial system, rather than perpetuating the skewed narrative that portrays farmers—who are labelled as a non-income tax-paying community—as holding the government to ransom. In reality, it is not just their own lives and livelihoods at stake, but also the food security of 80 crore fellow Indian citizens.

b.) The Silence of Academic Institutions

The continued silence of academic institutions, both public and private, is deeply troubling. When foreign-funded non-governmental organisations (NGOs) attempt to raise these critical issues, they are often dismissed as "anti-national" and face punitive measures under laws such as the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act (FCRA) and the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA). It is essential that individual analysts and scholars step forward to redirect the debate to where it rightfully belongs. Farmers, who lack both the financial and intellectual resources, cannot independently fund or present the necessary research to highlight their plight.

c.) The Role of Academia and Media Accountability

The responsibility, therefore, lies with the academic and intellectual community to shed light on the truth and ensure that the challenges facing farmers are understood in their full context. Meanwhile, the mainstream media has not only failed the Indian farmer but has actively contributed to constructing an anti-farmer narrative, further marginalising a community already struggling for survival. This concerted effort to silence dissent and misrepresent the realities of India's agricultural crisis must be challenged by independent thought and objective analysis.

Export Bans on India's Agricultural Commodities: Humongous Losses to the Farmers

Main Agricultural Commodities Facing Export Bans