The Sikh Sacrifice in the Valley of Terror: From the Chhattisinghpura Massacre to Pahalgam— the Unbroken Spirit

As we mourn the victims of Pahalgam, let us remember that the Sikhs of J&K are not just a community, but a living legacy—etched in blood at Chhattisinghpura, and echoed in the Gurbani of its Gurdwaras

Part A

The Massacre, Its Aftermath, and the Nation’s Moral Reckoning

The Pahalgam massacre of 22 April 2025, in which 28 unarmed tourists were savagely gunned down by Pakistan-backed terrorists, has not only shaken the nation’s conscience—it has also reopened an old, still-bleeding wound: the Chhattisinghpura massacre of 20 March 2000.

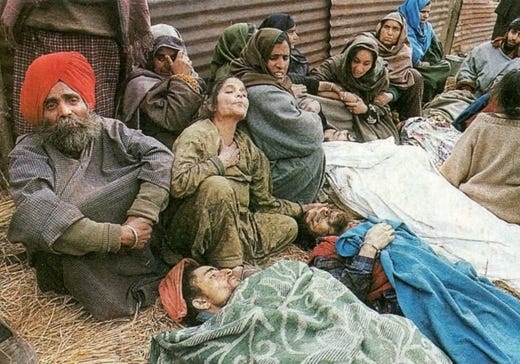

That evening, in the quiet Sikh village near Anantnag, 35 Sikh men and boys were executed at point-blank range by assailants dressed in Indian Army uniforms. It was the first large-scale targeted killing of Sikhs in the Kashmir Valley—an event etched in blood and memory.

Anatomy of the Massacre

The attackers—15 to 20 men clad in Indian Army fatigues—entered Chhattisinghpura under the pretext of a routine security operation. With cold precision, they ordered the Sikh men and boys to assemble near the village gurdwaras. Then, without a word of warning, they opened fire at point-blank range—a clinical, heartless execution. Teenagers and elders collapsed where they stood, their lives snuffed out in moments. Women and children were deliberately spared, but left paralysed by the horror unfolding before their eyes. Eyewitnesses recall that the gunmen spoke in Urdu and Kashmiri, laughed amidst the bloodshed, and coolly radioed a final message: “Mission accomplished.”

The massacre occurred just hours before U.S. President Bill Clinton landed in India—an unmistakable signal of sabotage designed to draw global attention, foment communal distrust, and derail India’s diplomatic momentum.

Truth Deferred: Investigations, Acquittals, and Allegations

In the aftermath of the massacre, the Indian government claimed that Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) militants were responsible, based on intelligence leads and confessions. Among those arrested was Mohammad Suhail Malik, a relative of LeT founder Hafiz Saeed. However, Malik was acquitted in 2011 for lack of admissible evidence. The case, far from offering closure, descended into a fog of contradictions.

Further anguish followed when allegations emerged that Indian Army personnel may have staged the massacre to implicate Pakistan. This theory, though never conclusively proven, was supported by retired Lt. Gen. K.S. Gill and others, and echoed across the Valley.

The suspicion deepened with the Pathribal encounter just five days later, on 25 March 2000. The Army announced it had killed five “foreign militants” responsible for the massacre. But residents insisted the dead were innocent civilians abducted and killed in a staged operation. DNA tests supported the villagers’ claims, but no one was punished.

Tensions exploded in Barakpora on 3 April 2000, when security forces opened fire on demonstrators demanding justice. Seven civilians, mostly teenagers, were killed in the crackdown.

Despite multiple investigations, inquiries, and public outrage, not a single person has ever been convicted. No commission report has been made public. For the Sikh community that cremated its martyrs with tears and turbans, the absence of justice remains an open wound—unforgotten, and unforgivable.

Resilience, Not Retreat

What followed was not an exodus, but an act of defiance rooted in faith. Unlike the forced migration of Kashmiri Pandits, the Sikhs of Chhattisinghpura chose to stay. They cremated their dead, rebuilt their homes, and refused to surrender to fear. Their strength was quiet but indomitable.

It was not born of vengeance—but of dignity. They believed in India, in justice, and in the sanctity of their soil. They still do.

Cautious Optimism, Eternal Vigilance

As India reels from Pahalgam and remembers Chhattisinghpura, one truth must be acknowledged: Pakistan remains committed to proxy warfare, exporting jihad under nuclear cover, while continuing to lie to the world.

Yet India must not descend into muscular symbolism or communal targeting. Our resolve must be cold, calculated, and morally clear. Let us honour the Sikh spirit—not just in memory, but in statecraft.

The Sikhs did not flee when bullets rained. They stood their ground. They chaanted and recited the name of Waheguru above cremation pyres lit with the flames of dignity.

May we, as a nation, remain worthy of such citizens. May Chhattisinghpura never happen again.

Part B

The Sikh Legacy in Jammu and Kashmir – A Historical and Cultural Footnote

Historical Sovereignty: From Sikh Empire to Dogra Rule

Before its accession to India, the region of Jammu and Kashmir was not merely a princely state—it had been part of the Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. In the early 19th century, Ranjit Singh’s forces established authority across the western Himalayas, including large parts of present-day Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh, and Gilgit-Baltistan. The Sikh military campaigns stabilised the region and integrated it into a multi-religious empire governed from Lahore.

Following the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–46) and the subsequent Treaty of Lahore, the British East India Company forced the weakened Sikh Empire to cede Kashmir. Under the Treaty of Amritsar (1846), the British sold the entire region of Jammu and Kashmir to Gulab Singh, a Dogra noble, for ₹75 lakh, effectively making him the Maharaja. Thus began the Dogra dynasty, which ruled until the state's accession to India in 1947.

This historical passage—from Sikh sovereignty to Dogra princely rule—helps explain the strong military, spiritual, and cultural ties Sikhs maintained with Kashmir, long before modern political boundaries emerged.

Roots That Run Deep

The Sikh presence in Jammu and Kashmir dates back centuries. Some trace their ancestry to Kashmiri Pandits and Muslim converts, while others settled during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in the early 19th century.

Today, as of 2025, Sikhs constitute 2–3% of the region’s population, concentrated in Anantnag, Srinagar, and parts of Jammu.

Spiritual Legacy: The Gurus and the Gurdwaras

Sikhism in Kashmir is hallowed by the footprints of the Gurus:

Guru Nanak Dev Ji preached in Mattan, Kargil, and Leh, emphasising peace and oneness.

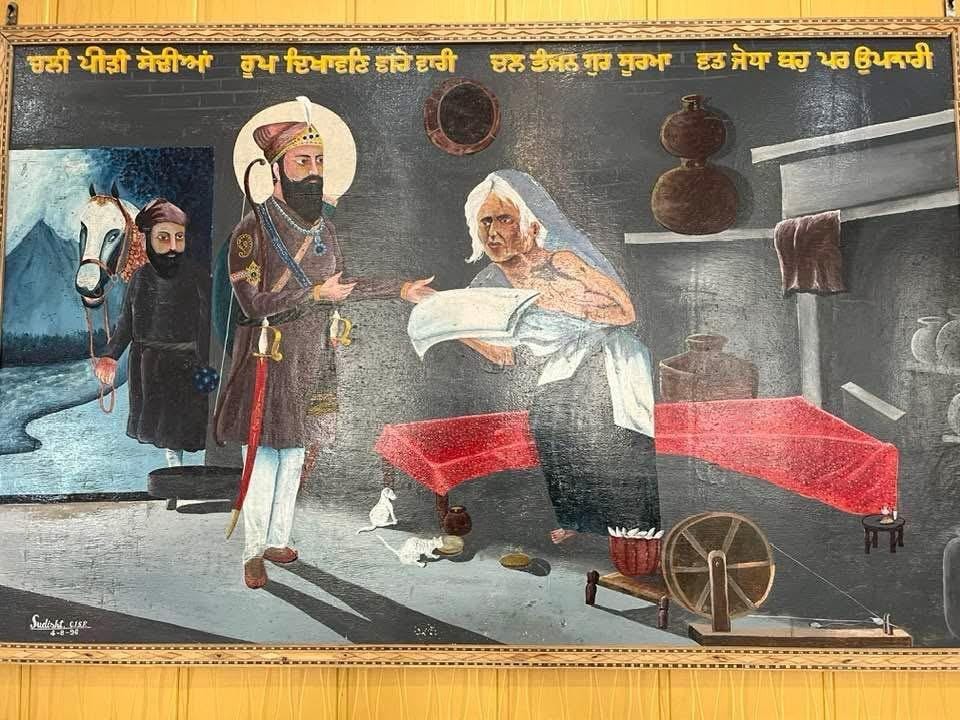

Guru Hargobind Sahib Ji spent three months in Srinagar in 1620. His visit is remembered for restoring the sight of Mai Bhag Bhari, a blind devotee1. Historic gurdwaras like Sri Guru Hargobind Sahib at Kathi Darwaza stand as testimony.

These shrines are managed largely by the Jammu and Kashmir Gurdwara Parbandhak Board, functioning independently from the SGPC but guided by the ‘maryada’ prescribed by it.

Linguistic and Cultural Marginalisation

The community's cultural expression faces official neglect. The Jammu and Kashmir Official Languages Act (2020) excluded Punjabi as an official language, despite its historical relevance and cultural significance to the Sikh population.

This move, seen as an insult, drew widespread protests. For a community already navigating survival, the erasure of language feels like the erasure of identity.

Defenders of the Land

Sikhs have stood as defenders of Kashmir in every war:

1947–48: Sikh regiments secured Srinagar and repelled tribal raiders.

1965 & 1971: Sikh units fought valiantly in the Pir Panjal and Poonch sectors.

1971 War: Flying Officer Nirmal Jit Singh Sekhon, the only Indian Air Force officer to receive the Param Vir Chakra, gave his life in the skies above Srinagar, bravely engaging Pakistani Sabre jets to protect the airbase and the Valley.

1999 Kargil Conflict: Sikh soldiers were among the martyrs, decorated for gallantry.

They have not only lived in Kashmir—they have fought for it, bled for it, and died for it.

Post-Article 370 Concerns

While the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 was meant to unify India, it sparked fears among Sikhs of demographic dilution. With over 83,000 non-locals receiving domicile certificates, worries about marginalisation have intensified.

Despite unwavering loyalty, the Sikh community lacks political representation and remains outside the scope of affirmative safeguards.

Closing Note

As we mourn the dead of the Pahalgam massacre, let us not forget the quiet courage of another tragedy, etched deeper into memory than into stone. The Sikhs of Jammu and Kashmir are not merely a community—they are a living, breathing legacy. Their history in the Valley is not preserved in archives or etched into laws, but woven into the sacred soil—in the blood spilled at Chhattisinghpura, in the footprints across the fields of Anantnag, and in the gentle hymns still sung in the gurdwaras of Mattan.

They are not outsiders. They are not an afterthought. They are a vital, enduring thread in Kashmir’s moral, cultural, and spiritual tapestry.

They do not ask for monuments or medals. They ask for no favours—only remembrance. Only justice. Only the dignity of belonging to the land where they have worshipped, suffered, served, and stood steadfast for generations.

To forget them would be a disservice. To remember them is not only honourable—it is necessary. Their silence has been noble—but let us not mistake it for indifference, nor allow it to become invisibility.

Gurdwara Chhevin Patshahi - Srinagar, is located on the banks of the Jhelum River and Dal Lake.

This site was visited by Guru Nanak Dev and Guru Hargobind the Chhevin Patshahi who visited the house of Mai Bhagbhari, who had long been yearning for a glimpse of the Guru when Guru Hargobind fulfilled her wish by his visit and wearing of her now famous gown or A well nearby marks the spot where the guru drew water to splash on mta bhagbharis eyes so she could have his Darshan.

Langar (Free community kitchen) and accommodation is available here round the clock.

Outside Punjab, J&K is the only state where there is a Gazetted Government holiday on Parkash Utsav of 6th Nanak Guru Hargobind Sahib. (From Poonam Khaira Sidhu Facebook Post of November 24, 2021).

Thanks so much for sharing KBS!