The River Waters Issue (SYL): A Chronicle of Continuous Injustices against Punjab

Punjab's Painful Odyssey: From Partition to River Rights

The story of Punjab, the land of five rivers, is deeply etched with the twin narratives of bounty and betrayal. Its rich tapestry, woven over millennia, has experienced significant ruptures in the not-so-distant past. The cataclysmic event of the Partition in 1947 dealt a crippling blow to the state, wrenching it apart, leading to unprecedented bloodshed and displacing millions. Families torn asunder, ancient communities uprooted, and a heritage fragmented – this was a trauma unparalleled in modern history. Deepening this painful episode, some of Punjab's prime lands, especially the recently established canal colonies, cultivated with generations of passion and effort, got left behind in what is today's West Punjab in Pakistan.

Yet, as the wounds of Partition were still raw and healing, Punjab faced another series of betrayals, this time over its lifeline - river waters. The state, which had already paid a disproportionately high price in lives, honour, and property, found itself grappling with another complex challenge. While the SYL canal has been in the spotlight recently, it is but one episode in a series of historical injustices that began soon after the dust of Partition settled.

The Indus Waters Treaty: A Momentary Victory

After the 1947 Partition, the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, brokered with World Bank mediation, shone as a ray of hope for East Punjab and PEPSU. Granting India unfettered access to the Ravi waters, this international pact with Pakistan had the potential to usher in an era of agricultural and economic affluence for Punjab. With its agricultural prowess, the state stood on the brink of harnessing this windfall to cement its stature as India's breadbasket. Alas, the expected turn of events remained elusive.

The 1955 Agreement: A Betrayal of Punjab's Interests

Even as negotiations for the Indus Waters Treaty promised a brighter horizon for Punjab, the 1955 inter-State agreement cast an unexpected and ominous shadow. This accord, to the dismay of many, ceded a massive 8 MAF of the life-sustaining Ravi-Beas waters to the non-riparian state of Rajasthan. At the heart of this perplexing decision stood Bhim Sen Sachar, a leader for Punjab often lauded for his forward-thinking vision. This very move, however, would be remembered as a glaring oversight or perhaps a profound misjudgement on his part. The question that lingers is: how could one sanction an agreement that generously parts with such precious resources without securing proportionate benefits for Punjab? This decision not only side-stepped the collective interests of Punjab but also that of PEPSU. In one fell swoop, the destiny of Punjab's waters took a turn, casting shadows that linger and challenges the state faces to this day. While some contend that this accord was pivotal for India to assert full rights over the Ravi waters, Punjab's dire need for irrigation makes such an argument appear tenuous at best.

Punjab Reorganisation Act, 1966: A Bone of Contention

The process of state reorganisation in India based on linguistic lines in 1956 was seen as a watershed moment. However, Punjab's journey to achieve its status as a Punjabi-speaking state was neither smooth nor straightforward. It required the vigorous ‘Punjabi Suba’ agitation to secure a separate state for Punjabi speakers. But the recognition came at a cost. Chandigarh, an integral part of Punjab, was declared a Union Territory, a status it uncomfortably retains even today. Moreover, significant Punjabi-speaking areas were either left out or, perplexingly, handed over to Haryana. To further add to Punjab's woes, its prized assets, crucial for its agrarian economy, were placed under the oversight of a central agency, the BBMB (Bhakra Beas Management Board). Yet, the most contentious part of the Punjab Reorganisation Act was the introduction of Section 78. This seemingly innocuous provision vested the Central Government with nearly unchecked authority to determine the allocation of river waters among the states.

The 1976 Notification: The Indira Gandhi Award and Its Consequences

Amid the tumult of the internal emergency, a pivotal notification was issued on 24th March 1976 under the aegis of Prime Minister Mrs. Indira Gandhi. This directive, stemming from Section 78 of the Punjab Reorganisation Act, exacerbated the water-sharing disputes, yielding an allocation that many saw as skewed against Punjab: Haryana, a non-riparian state, was granted 3.5 MAF out of undivided Punjab’s 7.2 MAF.

While Punjab, with its agrarian core, naturally sought a more equitable share to sustain its farmers, the division appeared disproportionately tilted in favour of other states. This imbalance not only stirred discontent within Punjab but also laid the foundation for ensuing conflicts. Punjab found itself in the irony of being India's food bowl, nourishing the nation, yet contending for its legitimate water share. The notification under Mrs. Gandhi's tenure was perceived by many in Punjab as another instance of central overreach, challenging the ethos of cooperative federalism. Far from resolving tensions, it intensified Punjab's tussles with its neighbours and the Centre, perpetuating the water disputes that still resonate today.

Mrs. Gandhi, Darbara Singh, and the Tripartite Agreement of 1981

The 1980s ushered in a seismic political shift in India. With Mrs. Indira Gandhi back in power by 1980, she centralised her reign, ousting multiple non-Congress state governments, including Punjab's. Amid this upheaval, the 31st December 1981 tripartite agreement between Punjab, Haryana, and the Centre was forged. This pact, recalibrating available Beas and Ravi supplies to 17.17 MAF, adjusted allocations: Punjab got 4.22 MAF, Haryana 3.50 MAF, Rajasthan 8.60 MAF, Delhi 0.20 MAF, and J&K 0.65 MAF. Notably, Delhi and Jammu & Kashmir emerged as new beneficiaries in this water-sharing narrative.

Punjab's Chief Minister, Darbara Singh's endorsement of this deal drew sharp criticism from many in Punjab, who perceived it as a betrayal and a compromise of the state's interests. This sentiment deepened as law and order plummeted, paving the way for militancy. Ironically, by October 1983, Darbara Singh's government was dismissed by the very central regime he had sought to placate. The events around this agreement not only strained Punjab's relationship with its waters but also diminished its voice in India's broader political discourse.

The Mirage of the Rajiv-Longowal Accord: Hope Dissolves into Disillusionment

The darkest chapter in the history of post-Independence Punjab unfurled in June 1984 with the tragic events surrounding Operation Blue Star, followed by Mrs. Indira Gandhi's assassination and the harrowing anti-Sikh pogrom in Delhi. These events cast a long shadow over the state's socio-political landscape, creating scars that are yet to fully heal.

The 1985 Rajiv-Longowal accord, in the aftermath of these tragic events, emerged as a glimmer of hope, a promise to end the turbulence that plagued Punjab. It was perceived as a bridge towards peace, re-establishment of democratic governance, and an avenue for reconciling outstanding differences. However, beneath its peaceful facade lurked decisions that would dent Punjab's interests further. The accord brought with it the controversial SYL Canal and the Eradi Tribunal, both of which had long-term implications on Punjab's right to its waters.

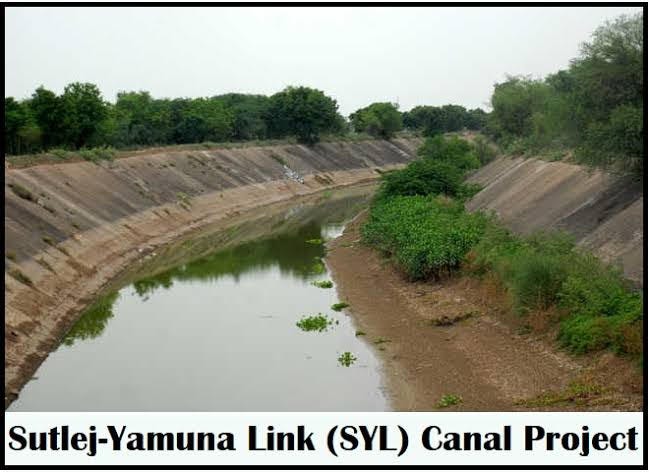

By January 1986, when Chandigarh's transfer to Punjab remained unexecuted, Chief Minister Surjit Singh Barnala should have paused the SYL operations in protest. Instead, his complacency allowed for the continued planning and eventual acceleration of SYL's land acquisition, particularly under President's rule after 1987. The canal, which is more than 90% complete in Punjab today, stands as a glaring testament to Punjab's eroding rights, while Chandigarh remained a Union Territory and Punjabi-speaking regions stayed detached from Punjab.

Barnala's tenure is a cautionary tale of missed opportunities and a palpable lack of moral fortitude. Despite his subsequent roles as a Union Minister and Governor, his legacy, in the collective memory of Punjab, remains tainted. While Sant Longowal met a tragic end through assassination and Finance Minister Balwant Singh was gunned down, Barnala's political journey continued. But for many, his inability to make the necessary sacrifices at crucial junctures – choices that could have profoundly benefitted Punjab – overshadows his later accomplishments. In Punjab's historical narrative, Barnala is often viewed as a leader who began with promise but whose thirst for power led him to compromise the state's long-term interests.

The Eradi Tribunal: An Albatross Around Punjab's Neck

In the intricate tapestry of Punjab's water disputes, the Eradi Tribunal looms large, not as a solution but as a perpetual reminder of the state's lingering burdens. Established under the Rajiv-Longowal accord, the Tribunal's findings were meant to pave a path to consensus. Instead, they further entangled the situation, seemingly biasing the scales away from Punjab's interests.

While the Tribunal might have reallocated the waters of Ravi and Beas, deeming the completion of the SYL canal imperative for Haryana's agriculture, its award didn't account for Punjab's age-old and deep-rooted connections to these rivers. Haryana's persistence in securing a larger share and Punjab's outright rejection of the Tribunal's findings showcased the intense distrust and dissatisfaction the verdict garnered.

The Tribunal's assertion of Haryana and Rajasthan as Indus Basin States, the validity of prior agreements, and the contention over Punjab's proprietary rights over Ravi-Beas waters added more layers of complexity. Rather than alleviating Punjab's concerns, the Eradi Tribunal became another thorn in its side, a burdensome legacy of the Rajiv-Longowal accord, casting a long shadow over the state's quest for its rightful share of waters.

The SYL Turmoil: A Decade of Unrest and Inaction (1988-2001)

The late '80s and '90s bore witness to the sheer intensity of the SYL dispute, marked by violent disruptions and a clear deadlock. In 1988, a tragic militant attack resulted in the death of 30 labourers at the canal's construction site in Majat, Ropar, further intensifying the fraught atmosphere. The continued unrest saw further casualties: Chief Engineer M.L. Sekhri and his assistant A.S. Aulakh, both working on the SYL canal, became victims of militancy in 1990. This violence coupled with the escalating turmoil forced the Punjab Government to halt the nearly completed construction. Despite Haryana's persistent appeals to various platforms, construction remained stagnant. Eventually, Haryana's plea to the Prime Minister in 1990 saw the Central Government attempting to delegate the task to the Border Roads Organization (BRO) in 1991. However, this move bore no fruit, leaving the canal untouched. Haryana, frustrated and desperate for resolution, approached the Supreme Court in 1995, refiling their suit in 1996. But even the judiciary, for the better part of the decade, did not bring closure to the issue, as the case remained unattended till 2001.

Haryana's Judicial Triumph: The Supreme Court's Rulings (2002-2004)

Between 2002 and 2004, the Supreme Court's verdicts noticeably tilted in favour of Haryana. In 2002, the Court unequivocally instructed the Punjab Government to complete the SYL Canal within a year, with the caveat that failing to do so would prompt Union Government intervention. Punjab's subsequent 2002 review petition faced rejection, and despite these clear directives, the canal construction languished. Seeking some reprieve, Punjab approached the Supreme Court in 2003, aspiring for a waiver from the SYL Canal construction mandate. Yet, the Apex Court's 2004 ruling remained steadfast, urging the Union Government to spearhead the project and demanding Punjab's full cooperation. This series of judgements in favour of Haryana was less a validation of Haryana's claims and more a reflection of the precedents set by Punjab's poor leadership decisions in 1955 and 1981, the contentious provisions of Section 78 and the biased Indira Gandhi Award of 1976, along with the Rajiv-Longowal accord.

Punjab's Countermove: The Termination of Water Agreements Act, 2004

Under the stewardship of Chief Minister Captain Amarinder Singh, the Punjab Vidhan Sabha made a strategically astute move by enacting the Punjab Termination of Water Agreements Act in 2004. This bold action is frequently lauded as a masterstroke in both political and legal circles. While it was eventually deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in November 2016 following a Presidential reference, it provided Punjab with a reprieve of over twelve years, insulating the state from implementing the prior decree as the issue awaited adjudication by a five-judge constitutional bench of the Supreme Court.

Unintended Consequences of the 2004 Act: Missed Opportunities and Lingering Shadows

For all its strengths, the 2004 Act unwittingly bolstered two major setbacks. Section 5 of the Act, designed to safeguard existing water usage, inadvertently ratified Punjab Vidhan Sabha's approval of the monumental 8 MAF of water allocation to the non-riparian state of Rajasthan under the contentious 1955 agreement. Furthermore, this Act cast an elongated shadow on the 1978 bilateral pact between Punjab and Jammu & Kashmir. The ambiguity surrounding agreement definitions inadvertently obstructed the timely execution of the Shahpur Kandi Dam project, even though the Ranjit Sagar Dam, initially called the Thein Dam, was already operational. While Captain Amarinder Singh's leadership in introducing the Act is commendable, the inadvertent concessions and the complications that arose cannot be brushed aside. Such oversights underscore the recurrent theme of missed opportunities in Punjab's water saga.

The 2016 Standoff: Supreme Court's Interventions and Punjab's Defiance

In early 2016, the SYL canal issue once again rose to prominence. The Supreme Court, responding to the plea of Haryana's newly-elected government, constituted a 5-Judge bench in February to deliberate on the Presidential Reference pertaining to the Punjab Termination of Agreements Act, 2004. This assessment, inter alia, sought to determine the Act's compliance with Section 78 of the Punjab Re-organisation Act 1966, which addressed the rights and liabilities of several states, including Punjab and Haryana. As proceedings got underway, the Solicitor General, representing the Centre, exhibited a noticeable tilt towards Haryana, upholding the Supreme Court's prior directives instructing Punjab to finalize the SYL canal's construction within its jurisdiction.

By March 2016, in a deft move showcasing its defiance, the Punjab Assembly greenlit the Punjab Satluj Yamuna Link Canal Land (Transfer of Proprietary Rights) Bill. Aimed at restoring the land rights back to the original farmers from whom the SYL canal land had been acquired, this act attempted to undo the Supreme Court's judgments from 2002 and 2004. In a symbolic gesture, Punjab's Chief Minister, Sh. Parkash Singh Badal, also sent a cheque to his Haryana counterpart, Sh. Manohar Lal Khattar, covering the canal's construction costs. This gesture, however, was swiftly rebuffed with the cheque's return. Haryana's swift countermove to the Supreme Court against Punjab's legislation intensified the tussle. Matters further escalated when Haryana threatened to disrupt water supply to Delhi, in response to the Delhi CM's position on SYL. By 17th March, the Apex Court, in an interim order, demanded a status quo on all SYL-related assets within Punjab and appointed key officials as 'joint receivers' of the SYL canal, while reserving its judgement on 12 May, 2016. Under these circumstances, the aforesaid Bill did not receive the assent of the Governor of Punjab.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Punjab's Legislative Challenge

On November 10, 2016, the Supreme Court of India delivered a unanimous (5-0) decisive judgment on the enduring SYL canal saga. "Punjab exceeded its legislative power in proceeding to nullify the decree of this court; thus, the Punjab Act cannot be considered a validly enacted legislation," ruled the bench, headed by Justice Anil R Dave. In a reference to its 2006 Mullaperiyar Dam judgment, the Court underscored the principle that a State Legislative Assembly cannot legislate in conflict with a judgment of the apex court, especially one that has achieved finality.

Punjab’s Executive Notification of November 2016: Reversion of Proprietary Rights

Despite the daunting aftermath of the November 2016 verdict, Punjab, steered by Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal, demonstrated legal acumen by issuing an executive notification to revert the proprietary rights of the SYL land to its original landowners. This strategic gambit, executed amid the spectre of potential contempt from the Supreme Court, resulted in numerous mutations reverting the acquired land to the original title-holders of the SYL canal. By the time the Apex Court could deliberate on Haryana's execution application of its civil suit decree, Punjab's masterstroke had essentially been implemented. During this intricate legal dance, I played a modest yet pivotal role, guiding and influencing certain decisions. For a more comprehensive perspective, I invite readers to my YouTube video, recorded shortly post my retirement from the IAS on 31st July 2021, delving deeper into this matter.

Notably, the said notification has not been invalidated or declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court to date. The issue resurfaced before the Supreme Court in early 2017, but was deferred, with the Attorney General of India suggesting that the Central Government would endeavour to mediate a harmonious resolution amongst the involved parties. The situation remained static until it was revisited in the Court earlier this week, bring the contentious SYL canal back into focus and public discourse.1

The Present Scenario and the Path Ahead

Punjab's successive defeats in various courts, more than being a reflection of its legal stance, underscore the political decisions and compromises made by its leaders over the decades. The 1955 agreement, the 1981 accord, and the 1985 Rajiv-Longowal accord stand out as monumental lapses.

While legal instruments like the 2004 Act and the 2016 executive notification have bought time, the impending hearing in the Supreme Court casts a shadow on Punjab's future. The current juncture demands unity among all pro-Punjab political parties. A collective appeal to the Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, is required, seeking a mutually acceptable resolution, with the non-negotiable clause that not a single drop of water flows to Haryana via the SYL Canal.

The days ahead are crucial. Punjab's history is filled with battles and compromises over its waters. Its future, however, must pivot on vigilance and unwavering commitment to its rights. Any leader or faction perceived as working against Punjab's interests, particularly those of its farmers, risks the unequivocal condemnation of its people. Punjab has already borne too much; it can ill-afford further sacrifices.

Conclusion: A Plea and a Cautionary Note

The river waters issue is not just a matter of legal rights or inter-state politics; it's deeply intertwined with the life, culture, and sustenance of Punjab. For centuries, the state's farmers have toiled on this land, ensuring not just the prosperity of Punjab but also significantly contributing to the food security of the nation. It's imperative that their rights and contributions are acknowledged and safeguarded.

As the matter again takes centre stage, it's a plea to the central leadership and Prime Minister Narendra Modi to intervene judiciously. The spirit of cooperative federalism, which the Indian polity so cherishes, must be brought to the forefront. An amicable solution that respects Punjab's rights and its people's sentiments is the need of the hour.

Simultaneously, it's a cautionary note to Punjab's leaders, past and present. The historical lapses must not be repeated. It's their duty to stand united, rise above party politics, and ensure Punjab's interests are non-negotiably protected. The stakes are high, and the repercussions of any misstep will echo through generations.

Punjab has weathered many storms, and with its indomitable spirit, it will see through this one too. But it's a collective responsibility, of its leaders and its people, to ensure that history, this time, is written in favour of justice, equity, and Punjab's rightful due.

Chronology of events.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1V8KiBf1uWZL_kYamBYlUIXQhr9dMuQq5/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=106723119440784079081&rtpof=true&sd=true