The 2007 Moga Sex Scandal: Sleaze, Systemic Collusion, and Convictions That Expose Institutional Decay

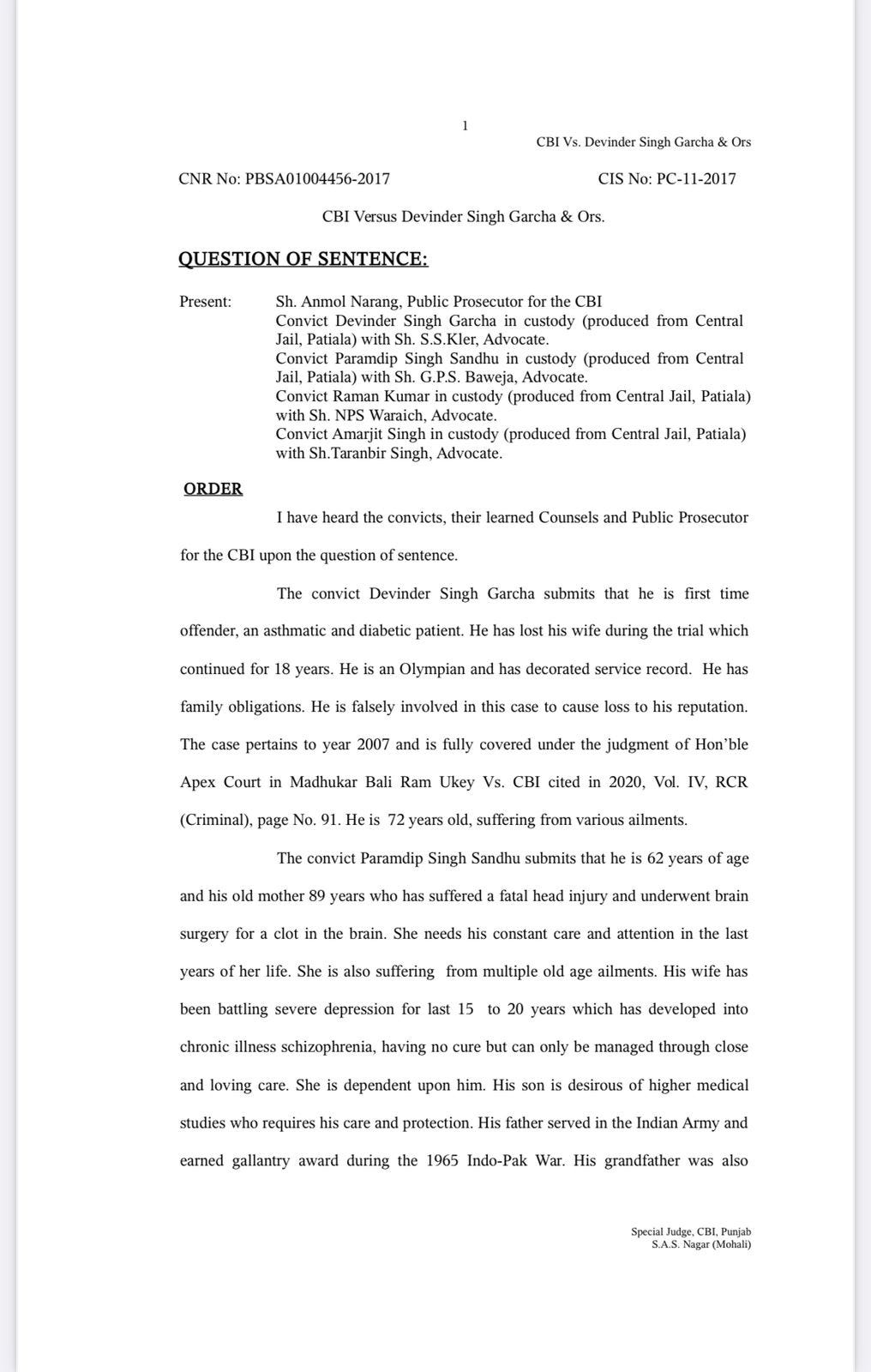

On June 6, 2018, while the trial in CBI court was still underway, Manjit Kaur, an accused, and her husband Rajpreet Singh were murdered in cold blood at their home in Pandori Khatriyan village, Zira.

Unearthing a Web of Institutionalized Extortion

The 2007 Moga sex scandal, which returned to public attention with the March 2025 convictions of four senior Punjab Police officers, is not merely a story of personal misconduct. It reflects a deeper institutional decay—of police complicity, political miscalculations, and a justice system burdened by delay.

Eighteen years after the scandal first broke, the Mohali-based Special CBI Court’s judgment against then-SSP Devinder Singh Garcha, SP Paramdip Singh Sandhu, SHO Raman Kumar, and Inspector Amarjit Singh has laid bare how the then sections of Punjab’s Moga district police hierarchy weaponized the law to run an extortion racket under the garb of protecting morality.

The convicted officers were handed reasonably stiff prison terms—ranging from five to eight years—and being over three years, these sentences will not normally entitle them to bail pending appeals, if any, that they may file in the High Court. These convictions, though delayed, bring to light a disquieting truth: when the guardians of law act as predators, justice becomes a long and painful journey.

Origins: From a Complaint to a Criminal Enterprise

The saga began in July 2007 when Manpreet Kaur of Jagraon, then a minor, alleged gangrape by four individuals at the Moga City Police Station. What initially presented itself as a conventional case of sexual violence soon snowballed into a larger conspiracy—an extortion and blackmail syndicate run with clinical precision and backed by police authority. The investigations revealed an unsettling pattern:

Luring and Entrapment: Women, including a minor, were used to trap men—many of them affluent or influential—into compromised situations.

Legal Threats for Extortion: Threats of false FIRs invoking charges under Sections 376 and 120-B IPC were used as a tool of blackmail, with amounts ranging from ₹50,000 to ₹1 lakh— reasonably hefty sums at that time— demanded for name deletion.

Coordinated Conspiracy: These police officers collaborated to fabricate affidavits, manipulate testimonies, and erase incriminating trails, thereby institutionalizing criminal behavior.

The Punjab and Haryana High Court’s intervention in December 2007, ordering the case’s transfer to the CBI, was a tacit admission that local law enforcement could no longer be trusted. A leaked audio clip of officers negotiating bribes gave the public its first real glimpse into the scale of the racket, leading to widespread outrage, leading to the transfer of the case to the country’s premier investigation agency.

Anatomy of a Cover-Up: Threats, Double Murders, and Judicial Delays

Elimination of the Prime Accused and the Long Arm of Fear

The CBI’s 2009 chargesheet named nine accused, including four police officers and two advocates and one Manjit Kaur who was not only running the racket but also allegedly coercing a minor girl into supporting false claims of rape and sexual abuse. The climate of fear and coercion was palpable.

Manjit Kaur, the prime accused who was allegedly at the helm of this sleazy sex-cum-extortion racket—often employing minor girls—was brutally murdered along with her husband in Zira in 20181. Their execution-style killing remains a chilling reminder of how far the racket’s reach extended, even years after the case had been transferred to the CBI.

Then a 17-year old minor girl, referred to as Manpreet Kaur in some media outlets, was once a star prosecution witness and CBI approver. However, she resiled from her testimony in 2010, turning hostile and citing immense police pressure at the time of her earlier sworn statement on oath before the Judicial Magistrate. As a result, the pardon granted to her was withdrawn by the Judicial Court, and her case was transferred to the juvenile court, where the trial against her is now stated to be at an advanced stage.

Many businessmen who were victims of the extortion ring refused to testify, paralyzed by fear of retaliation. Nevertheless, the testimony of a few has been relied upon by the trial court in securing convictions, underscoring both the atmosphere of intimidation and the resilience of those who chose to speak.

The Trial and Delayed Justice

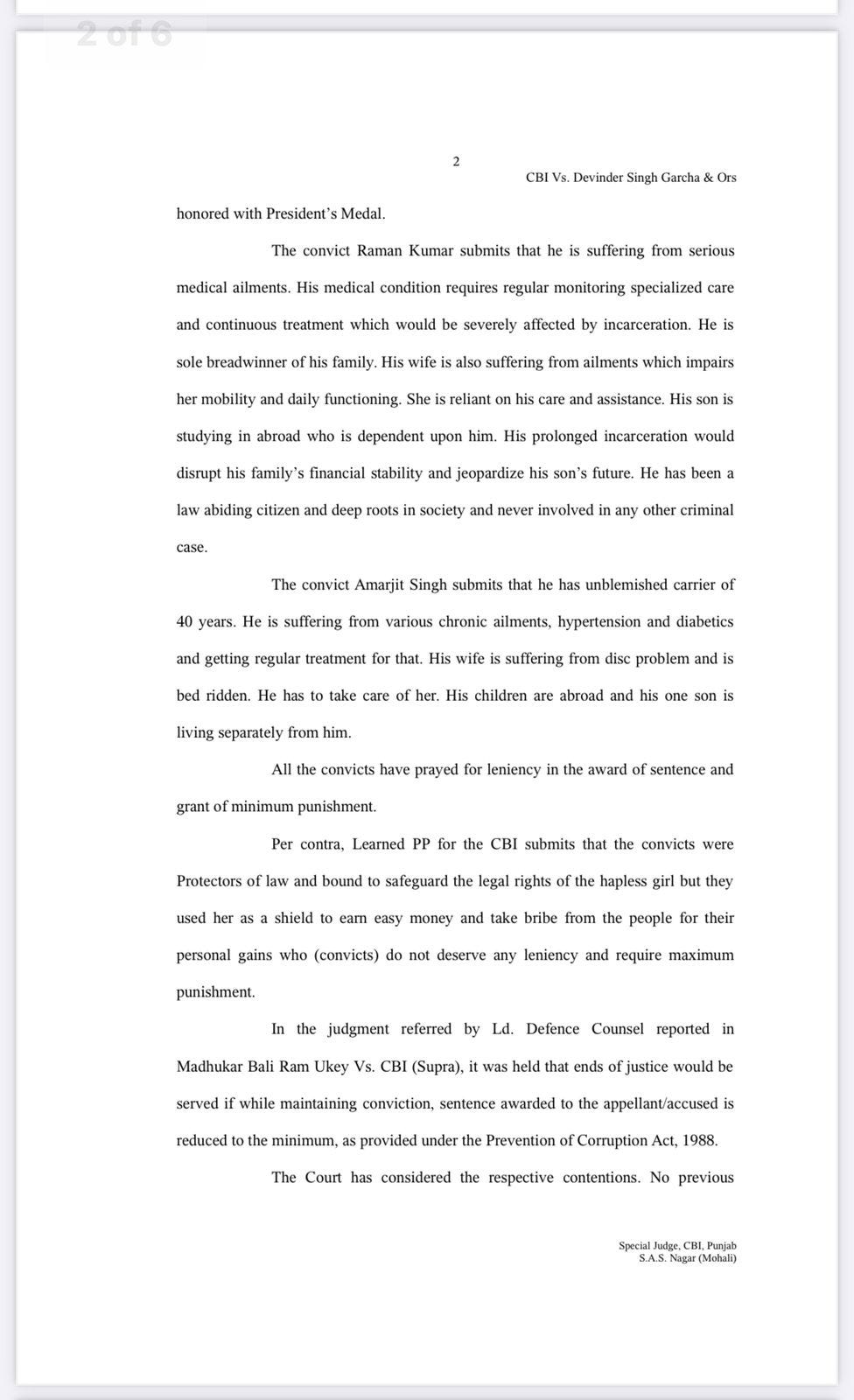

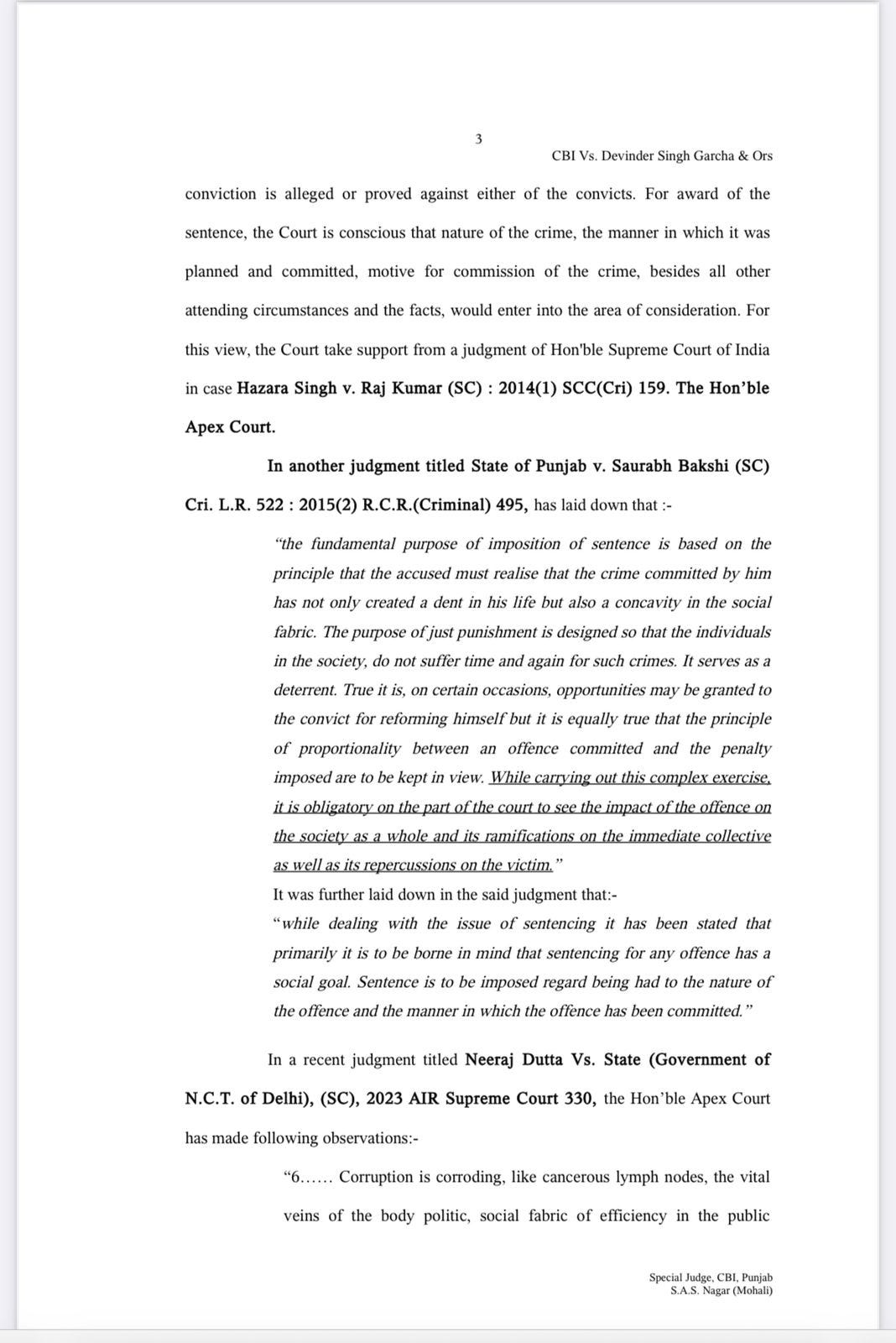

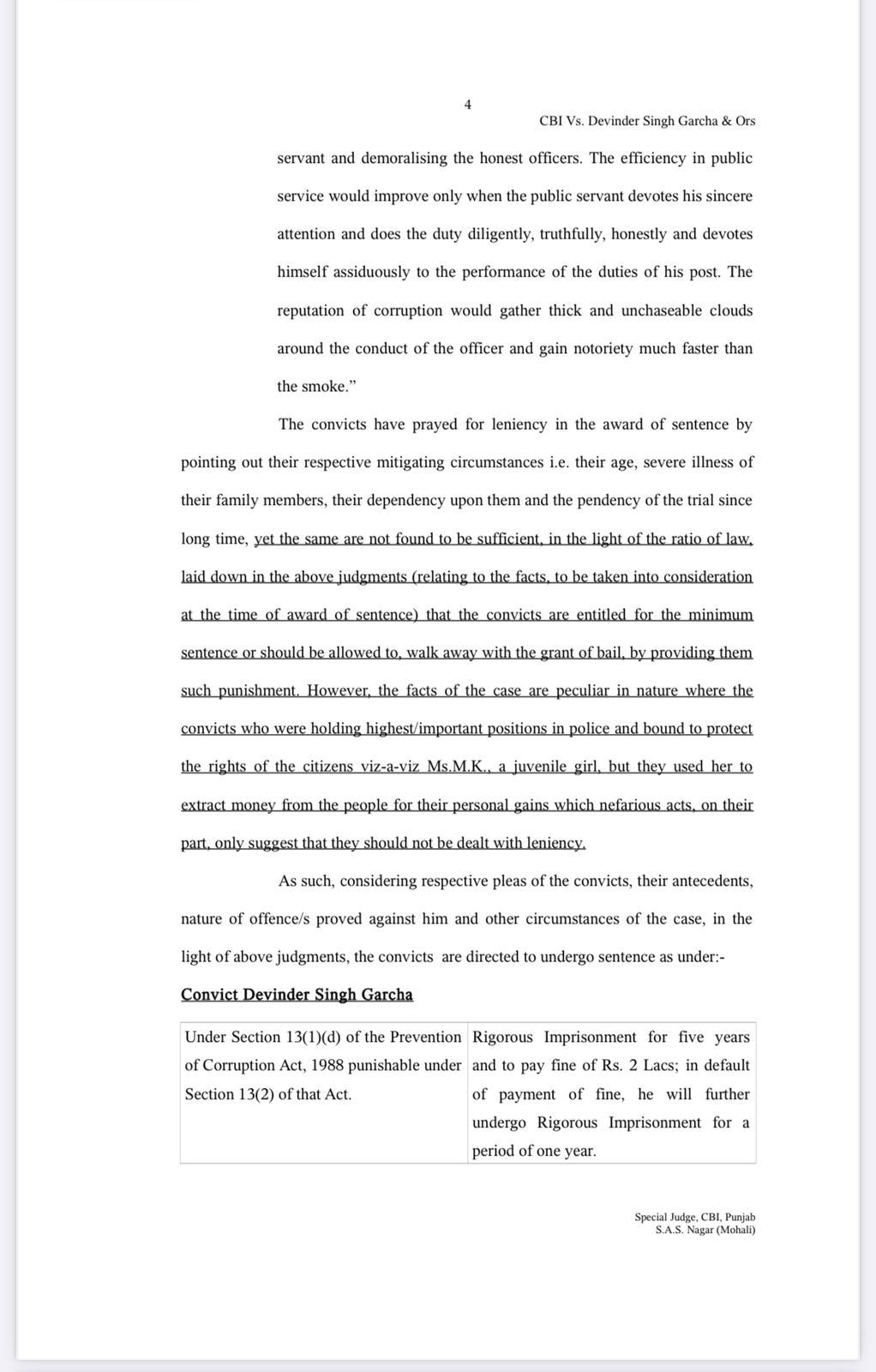

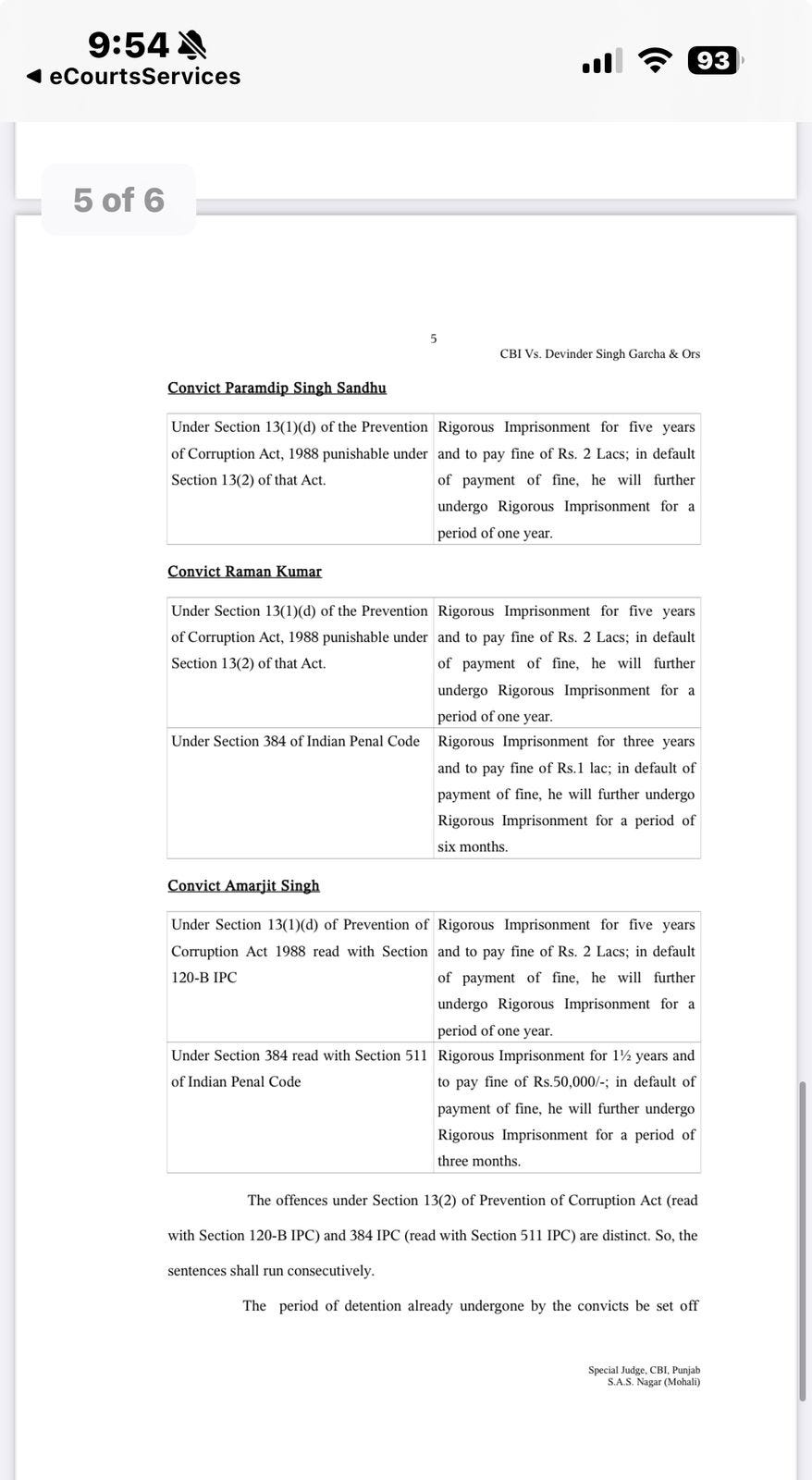

After multiple adjournments, slow-paced evidence collection, and fading memories, justice was finally delivered in March 2025. The Special CBI Court convicted four police officers under various provisions of the Prevention of Corruption Act and IPC:

Devinder Singh Garcha and Paramdip Singh Sandhu received five years’ rigorous imprisonment and fines of ₹2 lakh each.

Raman Kumar was sentenced to eight years, including three for extortion, along with a ₹3 lakh fine.

Amarjit Singh was awarded six and a half years with a ₹2.5 lakh fine.

The Ordeal of Barjinder Singh Brar: A Victim of Political Vendetta

Among those initially arraigned in the case was Barjinder Singh (Makhan) Brar, the son of senior Akali leader and former Education Minister Jathedar Tota Singh. Makhan Brar’s inclusion in the list of accused had less to do with prosecutable evidence and more with political vendetta and calculated mischief. The then-Congress government under Captain Amarinder Singh (2002–2007) had targeted several Akali Dal leaders, and Tota Singh was among those politically hounded during this period.

In 2007, although the Akali government returned to power, Jathedar Tota Singh lost the election from the Moga Vidhan Sabha constituency rather narrowly and was not holding any office of power. Nevertheless, with the impending Municipal Council elections in Moga, his son was somehow entangled in the case—a move that raised suspicions about the timing and intent behind his implication.

As the Badal-led Akali-BJP coalition assumed office in February 2007, the accused police officials, sensing a shift in political winds, may have opportunistically included Makhan Brar, perhaps in the hope that their proximity to the new ruling elite would lead to a quiet burial of the case, which was not to be since the case stood transferred to the CBI.

But far from being shielded, Barjinder Singh (Makhan) Brar endured a trial that stretched over more than a decade and a half. Despite his prominent lineage, he bore the full weight of an extended judicial ordeal. Ultimately, Brar was honourably acquitted and fully exonerated, with the court finding no credible evidence against him. His acquittal was not merely a personal vindication—it served as a powerful reminder that justice, though delayed, can still triumph, even for those ensnared in a web of political intrigue and institutional hostility.

Politically, the verdict comes as a shot in the arm for Makhan Brar as he now actively spearheads the new membership campaign for the Shiromani Akali Dal, under the banner of the 5-Member Committee constituted by Sri Akal Takht Sahib. Reports suggest he is receiving a rousing response, particularly from the rural heartland, where his outreach has struck a chord. Meanwhile, Sukhbir Badal has reportedly attempted to poach some of Brar’s key supporters, signaling a subtle yet unmistakable tussle for influence within the broader Panthic political landscape.

Leadership Failure and the Myth of Demoralization

Bureaucratic Inertia and Political Apathy

The then Akali-BJP government’s hesitant response and the earlier Congress regime’s strategic targeting created a climate in which justice was subverted by institutional cowardice. The police hierarchy, including then-DGP NPS Aulakh, downplayed the case, resisting CBI involvement and delaying action against senior officers.

Officers like Garcha and Sandhu were not suspended immediately and retained influence until formal charges were framed in 2012.

Political protection remained a recurring theme, but not for those like Brar, who instead became scapegoats in a wider power struggle.

The Demoralization Argument: A Convenient Excuse

The oft-repeated claim that holding officers accountable "demoralizes the force" was used yet again to stall reforms. This argument re-emerged during the 2025 Patiala incident, in which 12 policemen brutally assaulted Colonel Pushpinder Singh Bath and his son. Despite video and medical reports disproving the "intoxication" narrative floated by police, FIRs were delayed and excuses mounted. The district Chief’s tepid response mirrored the institutional apathy that prolonged the Moga scandal.

Lessons for Governance: Reforming the System, Restoring Trust

Ending the Culture of Impunity

The Moga scandal reaffirms the urgent need to enforce the Prakash Singh Police Reforms:

Fixed Tenures to curb political interference.

Independent Police Complaints Authorities to address grievances.

Witness Protection Schemes to encourage testimony without fear.

Making External Investigations the Norm

The CBI's role was pivotal in achieving convictions. Making external investigation agencies mandatory in cases involving senior law enforcement officers could ensure fairness, especially in politically sensitive matters.

Beyond “Bad Apples”

The Moga and Patiala incidents expose structural flaws rather than isolated cases. Shielding officers under the guise of morale protection only deepens public distrust. Real morale stems from accountability, not immunity.

Training in Ethics and Civil Accountability

Sustainable reform must include:

Ethics modules in police training.

Community policing models where citizens have a say in law enforcement.

Conclusion: Courage, Compromise but no Closure

The Moga scandal, with its deeply unsettling revelations and long-delayed verdicts, remains a tragic chapter in Punjab’s governance history. Yet within this dark tale lies the example of Barjinder Singh (Makhan) Brar, whose eventual acquittal reaffirms that even amid manufactured allegations and political vendettas, truth has a way of surfacing and succeeding.

The murders of prime accused like Manjit Kaur, turning hostile of the approver Manpreet Kaur and the 18-year journey of the case underscore the need for institutional courage and better protection programmes both for the accused and the witnesses. Reform cannot be held hostage by false fears of demoralization. It demands strength to discipline the guilty, protect the innocent, and rebuild a system that upholds the rule of law over politics.

Until that transformation is complete, the legacy of Moga will continue to haunt Punjab—not only as a cautionary tale of corruption and extortion but as a symbol of what it takes to stand vindicated when the system turns against you.

🔥 Blood on the Beas: The Woman Who Knew Too Much

The Accused Who Shook the System

Manjit Kaur was not merely a bystander to the Moga sex scandal—she was a central figure in the extortion racket, one whose network and manipulation were exploited to the hilt by the convicted officers. During the investigation, though she pleaded not guilty, she divulged critical details about how false rape allegations were fabricated, names were inserted into FIRs in exchange for bribes, and ordinary citizens were entrapped through the use of women—including minors—as bait.

Though her brutal death left her full legal reckoning incomplete, her disclosures laid the groundwork for the 2025 convictions of four senior Punjab Police officers. In a case where many were silenced by fear or coerced into submission, it was Manjit Kaur who paid the ultimate price—with her life.

Twin Murders Most Foul

On June 6, 2018, while the trial in the CBI court was still underway, Manjit Kaur and her husband Rajpreet Singh were murdered in cold blood at their home in Pandori Khatriyan village, Zira. The killers, masked and methodical, arrived with deadly intent. Armed with a .38-bore firearm, they shot both victims in the head at close range—an execution-style killing that left no chance of survival. They stole the CCTV hard drive to erase evidence, but nearby surveillance captured them fleeing on a motorcycle.

Manjit Kaur, who had changed her name to Prabhdeep Kaur for security reasons, was eight months pregnant at the time of her murder. The killings sent shockwaves through the local community—and sent a grim message to investigators: no one is beyond the reach of the forces she had once exposed.

Love, Betrayal, and a Staged Killing

The Punjab Police Special Investigation Team later claimed the murders stemmed from an illicit affair between Manjit (alias Sukhdip Kaur) and a man named Harjinder Singh. According to the SIT, Harjinder and his accomplices eliminated Rajpreet Singh because he opposed their relationship. Harjinder allegedly lured Rajpreet out for a walk, where he was abducted, strangled with a scarf, and dumped in the Beas River—his body wrapped in barbed wire and weighted with stones.

Multiple arrests followed. Some accused confessed. Others vanished. Yet, to this day, no one has been convicted for the double murder. The firearm's military-grade specification and the precision of the killing raised questions that remain unanswered. Was this merely a crime of passion? Or was it a targeted assassination—one meant to erase a woman who knew too much?

The Unsaid Testimony That Spoke?

Though she never lived to see the verdict, her leads proved very relevant in to the 2025 convictions of four police officers. In death, her voice continued to haunt the courtroom, lending force to a prosecution riddled with fear, silence, and suppressed truths.

A System That Did Nothing?

Despite being a key accused-turned-witness in a high-profile CBI investigation, Manjit Kaur received no witness protection, no security detail, no institutional safeguards. Her cold-blooded murder laid bare, once again, the gaping void in India’s justice system—where even those aiding prosecution in sensitive cases are left vulnerable to the wrath of entrenched power networks.

The story was no different for Manpreet Kaur, whose request to be turned approver had been accepted and a formal pardon granted—yet she eventually turned hostile, citing overwhelming pressure. Her retraction marked yet another failure of the system to protect those willing to testify.

No protection. No justice. No convictions in the double murder case. Just a silence that grows heavier with each passing year.

A Legacy Etched in Blood

Manjit Kaur’s life and death are a chilling reminder of what it means to speak out in a system designed to suppress truth. Though her death may have indirectly helped bring corrupt officers to justice, her killers still roam free. The double murder remains an open wound on Punjab’s conscience—a grim testament to the price of courage in a fractured and fragile system.

.

Not at all surprising in a country where Criminal justice system is a joke. Police protects police, Judges protect judges, politicians protect politicians. It is so unfortunate that Sr police officers at the rank of SP, SHO etc are so brutal and corrupt. Their formal education and training failed to make them good policemen who could deliver their duties towards people. Sikh values and Gurus' teachings could not make them good people. God only know how such people in police and in judiciary sleep peacefully in the night. The curse of poor who fell in the feet of these powerful catches up. I wish these guys and all others like them rot in jails for rest of their lives.

Not sure when will we see action on corrupt judges, or will we ever see action on corrupt judges. Supreme Court has it seems given all the judges a raksha kavach which will protect them.