Punjab Gets New Chief Secretary: A Reflection on Seniority and the Selection Process

Punjab's new Chief Secretary KAP Sinha takes charge. Given that the post of Chief Secretary is at least as important as that of the DGP, there is a strong case for codifying similar transparent norms.

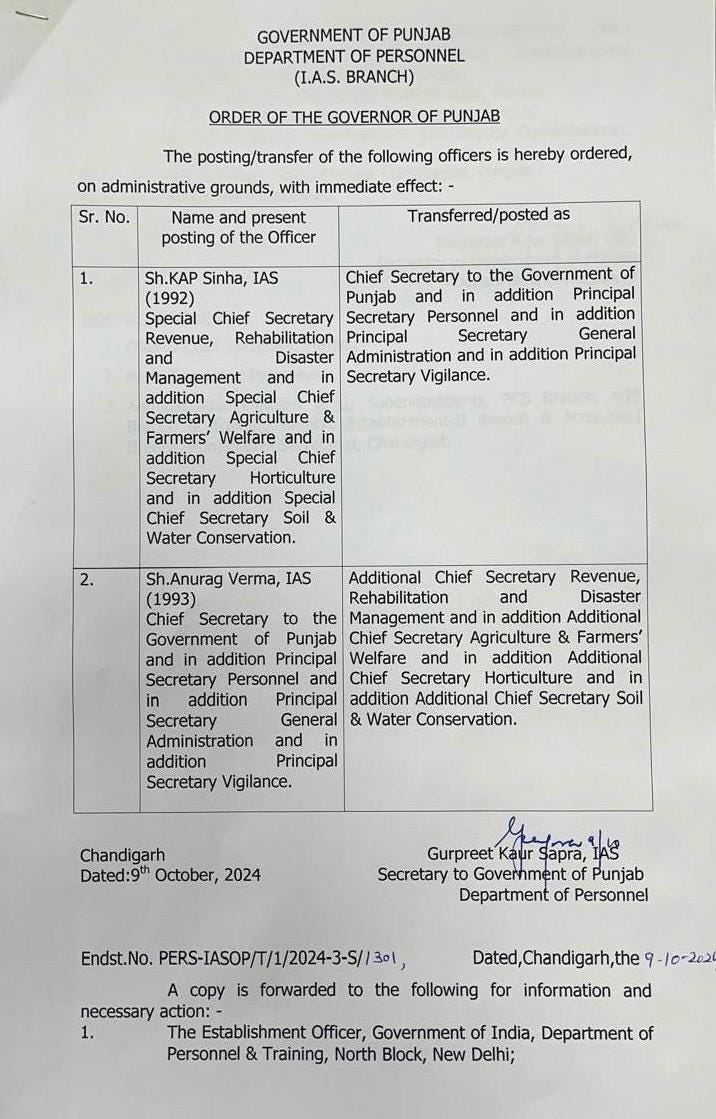

KAP Sinha Appointed as Chief Secretary of Punjab

Punjab today witnessed a significant shift in its administrative leadership with the appointment of KAP Sinha as the new Chief Secretary. Sinha, who has been serving as the Financial Commissioner Revenue-cum-Financial Commissioner Development, with designation of Special Chief Secretary, is a 1992 batch Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer. He replaces Anurag Verma from the 1993 batch. Both officers boast exemplary careers, but this time, Sinha's merit combined with his seniority has led to his selection for this prestigious role. Notably, Sinha had been overlooked when Verma was appointed in July last year, making this appointment a long-awaited recognition of his standing as well as performance within the cadre.

The Dynamics of Seniority in the Punjab IAS Cadre

It is worth noting that the seniority dynamics within the Punjab cadre of the IAS often play a pivotal role in appointments to key positions such as the Chief Secretary. KAP Sinha, being from the 1992 batch, is senior to Anurag Verma. Interestingly, several senior officers in the Punjab cadre, including Anirudh Tewari (1990 batch), the former Chief Secretary and now Director General of the Mahatma Gandhi State Institute of Public Administration, hold seniority over both Sinha and Verma. These officers, though overlooked for the Chief Secretary post, will now be designated as Special Chief Secretaries.

A Wider Pool for Selection: A Blessing or a Cause for Heartburn?

The practice of appointing Chief Secretaries in Indian states often involves choosing from a wide pool of officers. Generally, after completing 30 years of service, IAS officers across India are granted the apex scale, thus making them eligible for top positions such as the Chief Secretary. This creates a situation where Chief Ministers have a range of 6 to 7 batches of officers to choose from. While this wider selection allows the political executive more flexibility in making crucial appointments, it can also lead to dissatisfaction among senior officers who might feel overlooked despite an impeccable track record.

Reflections on Seniority and Overlooked Officers

The current system, prevalent across India, often leads to unnecessary frustration among senior IAS officers who, despite having impeccable service records and no adverse remarks, find themselves passed over in favour of their juniors. Neither the Government of India nor the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) is involved at any stage of the selection process, and there is typically no state-level screening committee to formally advise the Chief Minister on this crucial appointment. This lack of oversight can add to the perception of arbitrariness in these decisions.

While these overlooked officers may continue to draw the same salary, the reality is that they end up reporting to a Chief Secretary who is junior to them in in the gradation list. This creates a subtle but significant morale issue within the cadre, as senior officers may feel diminished, if not belittled, by having to take orders from someone they have outrank in terms of seniority. The situation becomes even more complex when these seniors are required to report to a junior officer who also writes their Performance Appraisal Report (PAR) or Annual Confidential Reports (ACRs), further exacerbating the feeling of professional discontent.

The Challenges of Central Deputation for Overlooked Officers

In many cases, officers who are overlooked for the post of Chief Secretary, or those who have been transferred or removed from the said apex position, often seek central deputation with the Government of India. Typically, these officers may move to New Delhi to serve as full-fledged Secretaries of a Ministry or Department. However, the process of empanelment as Secretary to the Government of India has become increasingly selective. There are numerous instances where even duly empanelled officers, who have expressed their preference for central deputation, are not chosen for these roles. This situation leaves them with limited options, forcing them to remain in the state capital and endure the professional disappointment and heartburn that accompanies being overlooked for the pivotal roles despite their eligibility.

It is important to clarify that I do not subscribe to the view that the Chief Secretary is merely "first among equals." The Chief Secretary is, without question, the undisputed head of the state’s civil administration, vested with the authority to provide overall direction and control. Irrespective of seniority, all officers within the state bureaucracy are expected to report to and function under the leadership of the Chief Secretary. This role is not a symbolic or ceremonial one; it carries real administrative weight, and the chain of command must be respected for effective governance. However, the emotional and professional toll of reporting to a junior can still linger for those senior officers passed over, even as they continue to fulfil their duties.

In this context, I would like to reproduce, with minimal changes, an article I had written in October 2021, shortly after my superannuation from the Punjab cadre IAS, titled "CMs violate IAS seniority rules too often with pick-and-choose game for Chief Secretaries," which was published in The Print, one of India's leading e-publications. The said piece delved into the intricate balancing act between merit, seniority, and the discretion of political leadership in the appointment of key IAS officers, particularly Chief Secretaries from an all-India perspective.

The Old Article

The Chief Secretary Appointment: Balancing Seniority, Merit, and Political Discretion

The position of the Chief Secretary is arguably the most crucial civil service post in any state. Normally, the senior-most serving Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer in the cadre is expected to be appointed to this role, with those on central deputation being overlooked. Apart from suitability, the only statutory requirement is that the officer should be on the Apex Scale of the IAS, typically granted after 30 years of service. This means that the political executive in the state often has a large pool of officers, spanning seven to eight IAS batches, to choose from.

Until a few years ago, seniority was the norm, unless the officer considered for supersession had only a few months of service left or was clearly unfit for the job due to service record, reputation, or other factors. However, this is now a custom more honoured in breach than in observance.

Outliers to the Seniority Principle

This first notable deviation from the seniority principle occurred in Tamil Nadu when P. Rama Mohana Rao, a 1985 batch IAS officer, was appointed as Chief Secretary in June 2016. Having served as Secretary to then-Chief Minister Jayalalithaa since 2011, Rao was appointed Chief Secretary, superseding 22 IAS officers, up to the 1981 batch, setting a striking but questionable precedent. His tenure, however, was short-lived, as he was removed in December 2016 after his residence was raided by the Income Tax Department—perhaps the only instance of a serving Chief Secretary being raided.

More recently, in June 2021, H.K. Dwivedi, a 1988 batch IAS officer, was appointed Chief Secretary of West Bengal, superseding nine officers from the 1984 batch and upwards. His predecessor, Alapan Bandyopadhyay, was similarly appointed in October 2020 over eight senior officers from the 1983 batch downwards.

In Punjab, the governments of Parkash Singh Badal and Captain Amarinder Singh have largely ignored seniority in selecting the Chief Secretary, with a few exceptions. When Captain Amarinder Singh took office in March 2017, he appointed a 1984 batch officer as Chief Secretary, superseding officers from the 1980, 1981, 1982, and 1983 batches. This trend continued when, in June 2020, a 1987 batch officer was appointed, bypassing three senior officers. Upon Captain Amarinder Singh’s departure, a 1990 batch officer was appointed Chief Secretary in September 2021, superseding officers from the 1987, 1988, and 1989 batches. The superseded officers are typically given the title of “Special Chief Secretary,” but they essentially perform the duties of administrative secretaries and report to their junior as Chief Secretary, who also evaluates their Annual Confidential Reports (ACRs).

In Rajasthan, a similar situation arose in November 2020, when Niranjan Kumar Arya, a 1989 batch IAS officer, was appointed Chief Secretary, superseding as many as 10 senior officers. Even today, nine IAS officers senior to him continue to serve, including one on central deputation.

Chief Minister’s Confidence: A Key Factor

Proponents of allowing the Chief Minister to choose an Apex Scale IAS officer, regardless of seniority, argue that the Chief Secretary must enjoy the complete confidence of the political executive. In a democracy, where the electorate has given the mandate to the Chief Minister to implement their developmental agenda, it is argued that the Chief Minister has every right to choose the most suitable officer from among the eligible candidates. The argument follows that the Chief Minister should not be constrained by the rigidities of seniority.

The Impact of Supersession on Civil Service Morale

However, purists in the civil service argue that superseding senior officers, apart from humiliating those overlooked, also demoralises the service as a whole. The uncertainty over when one might be removed from the position of Chief Secretary to make way for a junior can have a destabilising effect. While it is entirely justifiable to bypass officers with poor service records or questionable integrity, ignoring competent officers without a clear reason undermines the principles of a neutral, merit-based civil service. Unrestrained discretion in the hands of political leaders risks eroding the integrity of the civil administration, potentially leading to the slow disintegration of the steel frame that underpins India's governance.

A Case for Clearer Guidelines like in DGPs

The Supreme Court has already provided clear and mandatory guidelines for appointing Directors General of Police (DGP) to address similar issues of arbitrary selection. The procedure mandates that the state government send a panel of six senior-most IPS officers to the Union Public Service Commission, which, in consultation with the state’s Chief Secretary and serving DGP, returns a shortlist of three. The state government is then free to choose from among these officers. This system is not only fair but has also brought a degree of order to the previously chaotic DGP appointments.

Given that the post of Chief Secretary is at least as important as that of the DGP, there is a strong case for codifying similar transparent norms for the appointment of Chief Secretaries. Since the post of Chief Secretary is a “cadre post” under the statutory regulations framed by the All India Services Act, 1951, it is legally feasible to do so. The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) could take the initiative to establish such a procedure, similar to that for DGPs. Until such a framework is established, or the Supreme Court intervenes, the current practice of arbitrary appointments will persist, with Chief Secretaries sometimes appearing to be selected based on a subjective notion of “fit” rather than objective criteria.

A New Chief Secretary and the Broader Debate on Seniority and Appointments

The appointment of the new Chief Secretary has reignited discussions about the selection process for top administrative roles. While the buzz within the corridors of the Punjab Civil Secretariat at Chandigarh seems to centre on whether the increasingly assertive Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) high command "persuaded" Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann to make this change, the aim of this article is to foster a broader, nationwide dialogue—one that transcends individual personalities and state-specific politics.

That being said, we extend our sincere gratitude to Anurag Verma for his spotless tenure as Chief Secretary and wish him all the best in his new dual responsibilities. At the same time, we warmly congratulate KAP Sinha on his prestigious appointment and offer our best wishes as he takes on this onerous responsibility. This transition highlights not only the importance of who is chosen to lead but also how leadership transitions are managed within the civil service, a matter with significant implications nationwide. In a sensitive border state like Punjab, which faces escalating challenges on both the law and order and fiscal fronts, the leadership at the helm becomes all the more critical to navigating these pressing issues effectively1.

The original article was published on 5th October, 2021.