Of Gifts, ‘Nazranas’ and Favours: Different Hues of Political Donations

In world's largest democracy, donations made directly to individual political personalities, as opposed to registered political parties, reside in a gray area, both in terms of legality and ethicality

Introduction to Political Donations and Global Context

Three distinct, but unrelated, developments have recently highlighted the issue of gifts, ‘nazranas’, and favours of substantial pecuniary value received by political figures and public servants, including MPs and MLAs. This is not a phenomenon unique to India; it's as old as politics itself. For example, the Supreme Court of the United States only recently implemented a code of conduct for its lifetime-appointed judges after revelations that some had accepted and failed to disclose luxury vacations funded by US billionaires, and travel to an Alaskan fishing lodge on a private jet owned by a hedge fund tycoon with cases before the Court. Similarly, although Pakistan may not be the ideal exemplar of legal adherence, it has seen its former Prime Minister Imran Khan face legal action, including imprisonment, for misusing official gifts, from foreign dignitaries, intended for the state 'toshakhana' for personal benefit.

Case Study: TMC Lok Sabha MP Ms Mahua Moitra

As the proceedings of the TMC Lok Sabha, MP Mahua Moitra to unfolded before the Lok Sabha Ethics Committee, and her openly admitting acceptance of costly gifts, including Louis Vuitton bags, travel and hospitality from a business tycoon and friend became a part of public knowledge. Thereafter, questions have been raised as to what are the norms or guidelines for acceptance of such gifts, favours and ‘nazranas’, especially when like an MP or MLA, the person concerned does not take formal decisions like a Minister at Centre or in States, that could easily be construed as extending favours to the donees, as a quid pro quo for favours received or the future ones.

Regulatory Ambiguity in Political Donations

The question of donation through electoral bonds, though connected is entirely a different matter, and we have dealt in a recent article1 but acceptance of cash and other favours, including sponsoring of expenditure by politicians, whether sitting MLAs or MPs, or otherwise, during the election campaign, or in the normal period, is something which is widely existing in the country, but has never been put it into a formal overarching regulatory framework.

Contrast with Government Officers' Regulations

Unlike the political personalities, officers of the Government, including officers of All-India Services and Central Services have strict statutory rules regarding acceptance of gifts and intimation thereof. Not only this, acquisition as well as disposal of movable and immovable property by these public servants/officers, or their family members, is also strictly regulated by way of prior intimation and sanction from the competent cadre-controlling authority. Any breach of the same can invite disciplinary action under the relevant Conduct Rules, and in the ultimate cases, also lead to removal or dismissal from service, after due inquiry. It can also lead to criminal cases under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, especially if the public servant is found to be in possession of assets disproportionate to his known sources of income, at any time.

Income Tax Implications for Gifts and Donations

It may also be worthwhile to underscore that, under the general of the land, under the Income Tax Act, 1961 a gift received by a person, called the donee, is added to his income, except if it is from a very narrow set of close relatives, clearly defined in the law. In any case, cash payments of any form over Rs. 50,000 are generally not permitted. It may be noted that gifts include not only cash and cash equivalent, but also valuable assets like gold coins, costly cars, luxury travel and accommodation, and not to miss Louis Vuitton bags and celebrity-endorsed Prada spectacles.

Political Donations vs. Personal Gifts: Legal Distinctions

Many politicians, including ministers, MPs and MLAs routinely accept political donations in cash, which is supposed to be meant for funding their election campaigns, whether during the active period or otherwise. Their supporters or sponsors can also directly pay for huge public functions that might be organised for on behalf of these political personalities. All of these amount to gifts within the framework of the Income Tax Act, 1961 and, in theory, must be added to the assessable income of the person receiving them. It may also be underscored that the concept of political donations applies only when these are made to a political party that stands duly registered with the Election Commission of India. The donations which go into the personal accounts of individuals, irrespective of whether they are the office-bearers of such registered political parties, cannot be construed as political donations. These amount either to gift or, depending on the circumstances of the case, can also be construed as illegal gratification within the meaning of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988.

Election Campaign Expenditure and Legal Boundaries

During the campaign period, the expenditure made by candidate from the moment he is nominated, is added to the permissible expenditure allowed under the law, for the Lok Sabha or Vidhan Sabha elections. These limits now stand enhanced to rupees 75 lakh to 90 lakh and rupees 28 lakh to 40 lakhs respectively, depending on the size of the states involved. There is, however, no upper limit on what the political parties can spend on election campaigning out of their declared funds, including for the travel and campaigns of their so called “star campaigners”.

The Grey Area of Unofficial Campaign Expenditures

Under these circumstances, where any person, with the consent of the candidate, either makes any expenditure for on behalf of the contesting candidate, the same is added to the overall expenditure allowed, as per the extant legal provisions. Exceeding this threshold limit can lead not only to disqualification in future but also a substantial ground for setting aside of the election, in case the said candidate is declared to be the winning one. An argument which is open in advanced by the various contesting candidates is that the enthusiasm among the supporters is such that they go about spending huge amounts of money on their campaign, vehicles for canvassing, campaign public functions, as well as ‘langars’, voluntarily organised, that they have no control over them and not do they have any idea of the amount spent. Although, strictly speaking, the contesting candidate, may get away with this argument in so far as the election expenditure is concerned, the person making such expenditure without the written consent of the contesting candidate, actually commits an IPC offence under section 171H of the Indian Penal Code. However, it must be conceded that the punishment prescribed in such cases is really nominal and we have no data whether anyone has ever been convicted by a judicial court under this section.

Broader Implications on Democratic Governance

The receipt of gifts, favours, and pecuniary benefits by political personalities, whether serving as ministers, or as MLAs or MPs, or in general, whether during the campaign period or the otherwise, has far-reaching ramifications on the democratic and political governance of the country. It has also direct linkage with the compliance of the Income Tax Act, 1961 as well as the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, not to mention attracting the provisions of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. Unaccounted domestic money, especially from questionable sources, as well as from abroad, not only pollutes the political and democratic electoral process of the country, but also potentially has the capacity to subvert the same so that the collective will of the people does not get reflected in the outcome of the EVMs. Even donations from declared sources, when made to political personalities in their individual capacity, as distinct from donations to the registered political party, must also be set to sedulously scanned. This includes costly gift items, including precious jewellery and ornaments, which the Income Tax Department often described as “gifts without occasion and without relation.”

The Need for Transparency and Accountability

The question here is not whether the receipt of these gifts, favours and ‘nazranas’ will actually sway the act and conduct or the decisions of the recipient public servant or the political personality, but one of openness and transparency. As the proceedings of the Lok Sabha Ethics Committee, in the case of Ms Mahua Moitra revealed, there does not appear to be any formal code of conduct governing such gifts by the Members of Parliament. To the best of our knowledge and belief, the same is the position in the various state legislative assemblies. Nevertheless, exchange of gifts is not only rampant, but widespread all across the country, especially on auspicious occasions like Diwali – these, of course, spike, as soon as the elections are announced. It is no one’s case that the so-called political donations are in nature of extortions and 99% of the cases, the donor is voluntarily making the same. Whether it is an investment, in hope for receiving future favours is an entirely different matter.

Potential Reforms in Political Donation Regulations

The Indian electoral democracy has evolved a long way since the first general elections were held in the year 1952. It must be underscored that due diligence must be exercised not only during the campaign period but also otherwise at all times. What is required at the moment is a central law regulating the receipt of such political donations, gifts, pecuniary favours, and ‘nazranas’ by political personalities, especially MPs and MLAs. Whether any upper limits have to be laid down in terms of receipt from one particular donor is entirely a different matter, but each and every gift so received must be either proactively declared or prior sanction obtained. The threshold as applicable to the Members of the All-India Services would be a good benchmark to adopt.

Such a statutory framework would be toothless unless penalties by way of disqualification and suspension are provided as a part and parcel of the same. The penal proceedings under the new proposed law should be distinct from formal investigation and prosecution under existing laws such as the Income Tax Act, 196, the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, and the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, which take decades to complete before the judicial criminal courts. These should be in the nature of civil or quasi-criminal proceedings, with a summary procedure, where a conviction doesn’t follow but lead to disqualification from being an MP or an MLA, including a bar for a few years in future. It is submitted that it is not the severity of the punishment but the certainty of punishment that is a deterrent.

Concluding Thoughts: A Call for Legal Reform and Civic Responsibility

It is also submitted that the disqualification process must be left not to the in-house committees of the Parliament, but to the independent judiciary – preferably the High Court in case of MLAs, who are already courts of original jurisdiction for hearing election petitions of not only MLAs but also of MPs. It is suggested that in case of the MPs, the matter should go directly to the Supreme Court.

The question of political donations is an important one and needs to be addressed expeditiously. The contentious Mahua Moitra episode has merely highlighted an issue which has always existed but often brushed under the carpet. The new proposed law must be fair, just and reasonable and not one which becomes an instrument of political witchhunt, which, in the long run, turns counter-productive, as the political cycles and the political climate in the country changes. The proposed enactment is something which requires not only consensus amongst the various political parties, but also widespread consultation with all the stakeholders, including civil society, representatives, NGOs, retired judges, and bureaucrats, eminent journalists, as a matter of fact from general public.

We all owe it as the country for this law to be in place. If and when it shall come is something we need to closely watch. As an active citizen, it is your duty to push for the same within your social circle, either personally or through digital means.

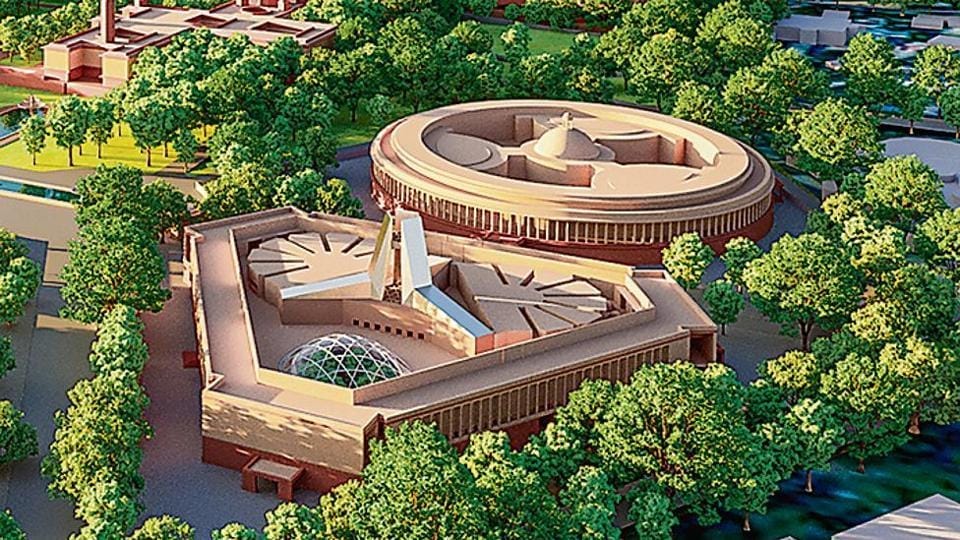

Electoral Bonds— Supreme Court hearing begins on 31st October

Electoral Bonds Scheme: Supreme Court to commence hearing from 31st October The Supreme Court has scheduled the commencement of hearings for the various petitions challenging India's "Electoral Bonds Scheme" on October 31, with expectat…