India's Middle Class Staring into a Bleak Diwali

The Indian middle class deserves more than mere praise; it needs concrete policies and decisive action to secure its resilience, survival, and growth.

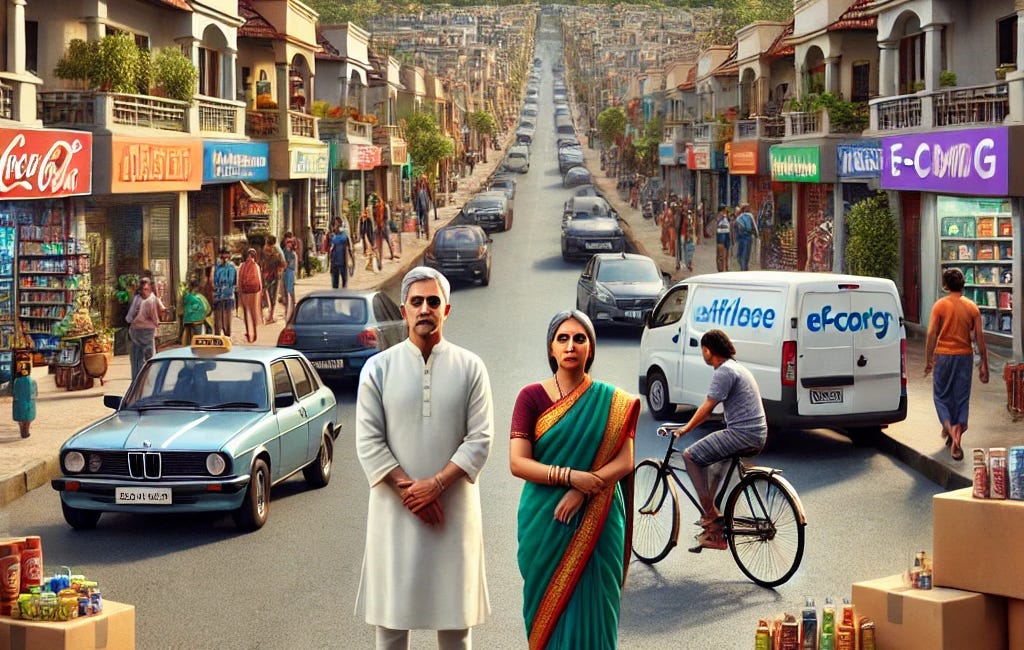

Middle Class Under Stress

The Indian middle class, the proverbial backbone of the nation’s economy, is under tremendous stress, with cracks now visibly emerging. Yet, the cheerleaders of the central government, particularly within the finance ministry, seem oblivious to both qualitative and quantitative signs of this strain. While India’s projected growth rate for 2024-25 stands around 7%, and the IMF’s broad estimate for 2025-26 moderates to 6.5%, the future outlook for the middle class is far from promising.

The financial health of the Indian middle class is critical, as it bears a disproportionate share of the nation’s tax burden. In a country with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, the number of income tax filers remains limited. As previously noted, however, GST ensures that virtually every citizen is a taxpayer, at least in consumption terms. The consistently high GST collections suggest that mandatory spending persists while discretionary spending has taken a hit—a trend partly driven by inflation.

Let’s examine some key indicators:

1. FMCG Sector Under Stress

Executives from major FMCG companies such as Nestlé India and Hindustan Unilever (HUL) underscore the distress within the middle class. Suresh Narayanan, Chairman and MD of Nestlé India, has pointed to a "shrinking middle class" affecting FMCG sales, echoed by HUL’s reports of challenging conditions.

Nestlé reported its slowest quarterly growth in eight years, and HUL’s net profit grew by a modest 1%. Notably, volume growth has been hit hard, with Nestlé experiencing a 1% decline and HUL only a 2% rise. This indicates that consumers, especially middle-income earners, are buying less.

Interestingly, both CEOs observed that premium products still perform well, suggesting an income divide: affluent consumers continue to spend, while the middle class cuts back1.

2. Automotive Sector Woes

The automotive sector, a traditional economic barometer, is also under considerable pressure. Auto dealerships are currently burdened with inventories valued at INR 79,000 crore, with the Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations (FADA) reporting record-high stock levels of 80-85 days. Notably, the INR 10 lakh–INR 25 lakh segment, which predominantly serves the middle class, has witnessed a sudden and marked decline in sales, reinforcing signs of middle-class distress. This dip persists despite aggressive efforts by banks and NBFCs to push auto loans to prospective buyers.

3. Sluggish Bank Deposit Growth

Bank deposits have been growing, albeit at a slower rate than credit growth until recently. As of September 2024, deposit growth reached 7.3%, amounting to INR 215.5 lakh crore. However, much of this growth stems from accrued interest on existing deposits rather than fresh inflows, casting doubts on the middle-class saving capacity. While some had previously attributed this trend to funds shifting into debt mutual funds due to favourable tax treatment, this incentive has since been removed. The only reasonable conclusion, therefore, is that the middle class is now constrained to save less as mandatory spending continues to rise alongside persistent inflation.

3-A. Credit Card Debt: A Middle-Class Proxy

Credit card debt in India has risen sharply, reaching INR 2.7 lakh crore in June 2024, up from INR 2 lakh crore in March 2023. This marks a compound annual growth rate of 24% over five years. Worryingly, credit card defaults have also increased to 1.8% of total outstanding, underscoring a disturbing trend: middle-class consumers are increasingly reliant on credit to sustain their lifestyles, risking a debt trap.

4. Inflation and Interest Rates

Inflation remains stubbornly high, reaching 5.49% in September 2024, fuelled largely by a sharp rise in food prices. Although the RBI might term this inflation rate as “moderate,” steep price hikes in specific categories—especially seasonal vegetables—are exerting considerable pressure on the middle class. In response, the Reserve Bank of India has maintained elevated interest rates, keeping borrowing costs high and stifling both industrial development and investment. This combination of sustained inflation and high interest rates creates a particularly challenging environment for middle-class borrowers, especially the salaried segment, and casts a long shadow over broader economic growth.

5. Income Tax Assessees and Collections

India’s income tax data further underscores the financial squeeze facing the middle class. For the Assessment Year (AY) 2024-25, over 7.28 crore Income Tax Returns (ITRs) were filed by the 31 July 2024 deadline—a 7.5% increase compared to the previous year. However, first-time filers accounted for only 58.57 lakh of these returns. This figure, representing individuals not subject to compulsory tax audit, serves as a meaningful indicator of the middle class’s financial participation.

Comparing year-over-year filings provides additional context: in AY 2023-24, 6.77 crore returns were filed by the deadline, rising to 7.42 crore by August 2024. While the absolute increase in ITR filings appears promising, the broader picture reveals limitations. Net direct tax collections saw a 22.5% rise year-on-year, reaching INR 6.93 lakh crore by August 2024. Yet, when adjusted for refunds and inflation, the real growth in tax collections is modest, revealing a more restrained increase in middle-class income contributions.

Crucially, the income tax growth rate significantly outpaces the growth in the number of filers, strongly suggesting that income gains are concentrated in the top percentile of the middle class or among higher-income groups. This imbalance is a telling sign of middle-class strain, with limited upward mobility and stagnating financial progress for the broader segment. In essence, the bulk of income growth lies outside the core middle class—a clear signal of mounting economic stress within this critical demographic.

6. Manufacturing Sector Challenges

Despite the ambitious "Make in India" initiative, India’s manufacturing growth remains heavily concentrated in government-subsidised sectors like computers and mobile phones, primarily through the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme. However, much of this activity involves basic assembly of imported components rather than genuine, value-added manufacturing, with high customs duties often pushing up costs for Indian consumers. While substantial subsidies have recently been allocated to high-performance GPU and semiconductor chip manufacturing, the impact on the global market is expected to be limited, generating low employment and modest economic ripple effects domestically.

In affordable consumer goods, India lags far behind China, and in advanced manufacturing and capital goods, it has yet to approach the sophistication of the US and Western Europe. Despite continuous, high-volume trade with China—where imports have not significantly declined—the broader vision of self-reliance in manufacturing remains largely unrealised. Without a transformative, systemic approach to bridge these gaps, “Make in India” risks staying more slogan than reality, falling short of the kind of shift needed to position India as a serious player on the global manufacturing stage.

7. Agricultural Sector Stress

Agriculture, the backbone of a significant portion of the lower middle class, continues to grapple with mounting debt, soaring input costs, and stagnant incomes. Farmers, already strained by inflation and minimal income growth, face additional pressures from non-remunerative procurement prices and an oversupply of paddy flooding Punjab’s mandis. The paddy glut has led to mounting frustration, with farmers caught in the crossfire of a blame game between the state and central governments. Each points fingers at the other over pricing and procurement responsibilities, leaving the agricultural community and, by extension, the wider middle class, bearing the brunt of policy shortcomings and economic strain.

8. Stock Market Performance: A Misleading Indicator

Indian stock markets have soared, with the NIFTY 50 and Sensex indices more than doubling since 2019, fuelling record contributions to Systematic Investment Plans (SIPs). Yet, this apparent prosperity largely favours high-income groups and corporates, whose impressive topline and bottom-line growth often comes at the expense of middle-class consumers. Robust profits for companies are frequently driven by pricing strategies that place an additional burden on the middle class, highlighting an economic divide where market gains are not equitably shared across income groups.

9. The Unemployment Surge Among Educated Youth

Unemployment is becoming an alarming issue for India’s youth, particularly among the educated from the middle-classes. In 2024, the unemployment rate for young Indians aged 15-29 stands at 12.9%, nearly double the national average of 7.1%. The situation is even bleaker for those with graduate degrees or higher, with an unemployment rate reaching 17.3%, underscoring the gap between education and employment opportunities. India’s once-promising startup ecosystem, seen as a potential job creator, has shown signs of stagnation; newly registered startups have plateaued at around 12,000 annually for the last three years, while funding has dropped by 36% in 2023 compared to the previous year.

10. The Impact of Technological Disruption and Unfulfilled Promises

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) introduces further uncertainty to the employment landscape. A recent McKinsey Global Institute report estimates that up to 30% of work hours across India could be automated by 2030, potentially displacing 120 million jobs, particularly in mid-skill roles crucial to the middle class. Frustration is rising among youth, as seen in increasing incidents of unrest. Government initiatives like the Agniveer scheme, intended to absorb unemployed youth into military service, have faced criticism, with only 25% of Agniveers retained after four years. This lack of long-term job security has led to disappointment and exacerbated youth disillusionment. The convergence of high unemployment, AI-driven disruption, and limited success of government schemes casts a worrying shadow on India’s youth employment prospects and, if left unaddressed, could lead to social instability.

The Urgent Case for Middle-Class Revival

The middle class, long celebrated by the ruling party as the aspirational engine of India’s economic rise, is now facing unprecedented strain. As multinational CEOs openly speak about declining sales and shrinking consumer demand, the reality of middle-class distress can no longer be ignored.

Signs of this strain are everywhere: sluggish deposit growth, rising credit card debt, and stagnant income tax data reflect a middle class that is no longer growing as expected. This is a crucial moment for India’s policymakers. The government, finance ministry, and RBI must urgently collaborate with all stakeholders to undertake a comprehensive review of middle-class economic health. Immediate, targeted action is essential—not just to drive growth, but to address the real and pressing challenges confronting India’s middle-income earners.

Inaction risks deepening the cracks into unbridgeable chasms, bringing a spiralling economic crisis closer to reality than we may wish to admit. This isn’t merely about reframing criticism of a “squeezed middle”; it’s about averting a potential economic disaster. The Indian middle class—long the backbone of national resilience—deserves more than rhetorical praise. It demands concrete policies and decisive action to support its survival, resilience, and potential for growth.

India's Vanishing Middle Class: Phenomenon and Implications

CEO of Nestlé India's Comments Stir Debate