India Scraps Minimum Export Price for Basmati Rice to Boost Global Competitiveness

Commerce Minister Hails Decision as Pro-Farmer; Farmer Leaders Express Skepticism.

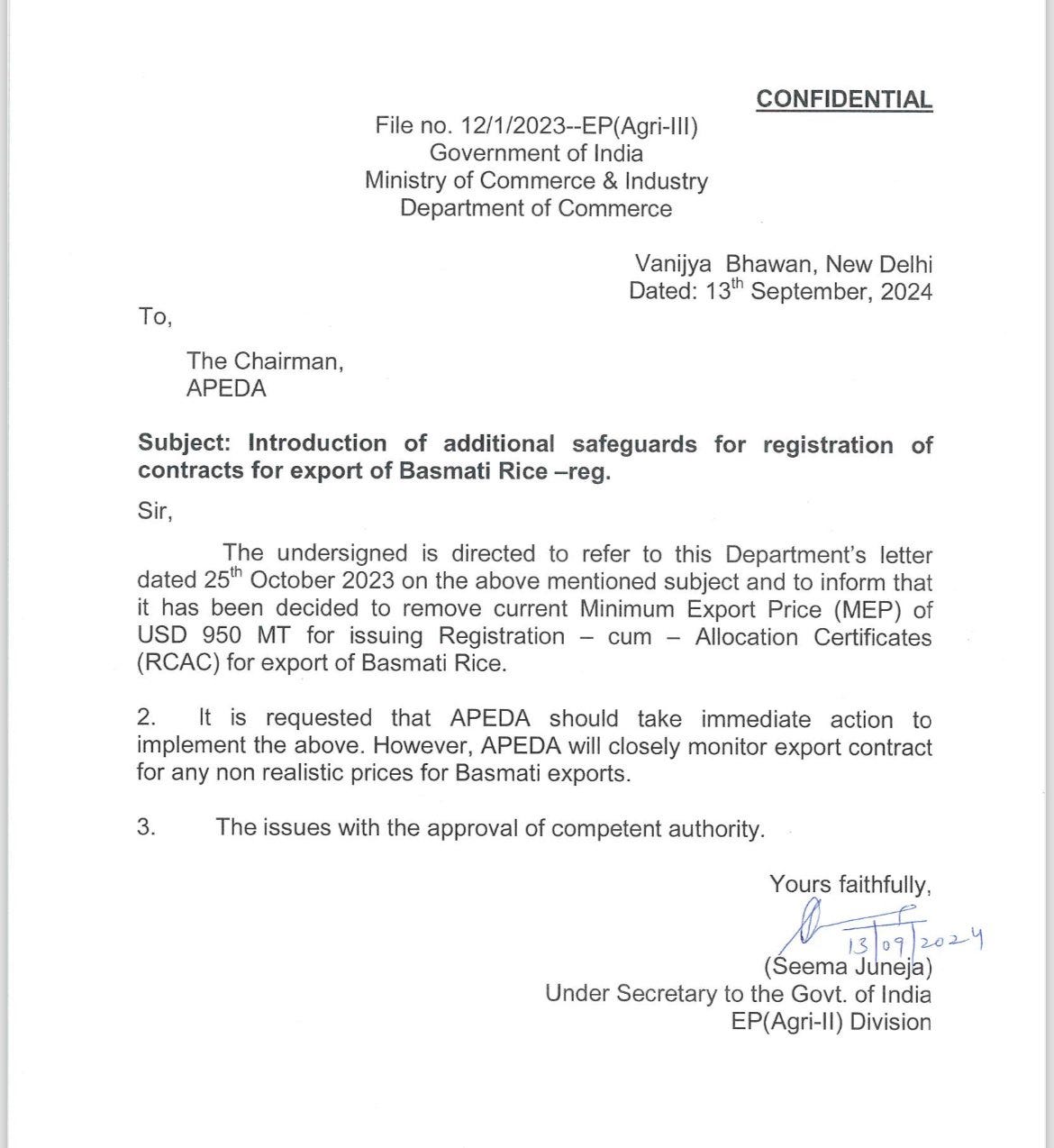

Government Removes the Minimum Export Price (MEP) for Basmati Exports

In a significant move aimed at boosting the export of Basmati rice, the Government of India on 13th September announced the complete removal of the Minimum Export Price (MEP) for Basmati rice. The policy, introduced to regulate export floor prices, has been met with mixed reactions from stakeholders, including exporters, farmers, and agricultural analysts. This article provides a rudimentary analysis of why MEP was implemented, how it evolved, and the implications of its recent removal1.

The Rationale Behind MEP for Basmati Exports

The MEP for Basmati rice was initially introduced as a regulatory measure by the Government of India to maintain the price levels of rice exports and prevent the export of non-Basmati rice being passed off as Basmati. By setting a price floor, the government sought to ensure that high-quality Basmati rice was sold at a reasonable price in international markets, protecting the interests of Indian exporters and safeguarding the quality perception of the product globally, while proving a safety-net to the farmers who could potentially be forced into parting with their produce to the exporters at unremunerative prices2.

Additionally, the MEP aimed to curb illegal exports of non-Basmati rice and to maintain the country's domestic rice reserves by regulating the volume of Basmati rice leaving the country. At the same time, the MEP was seen as a tool to protect domestic food security and the inland consumers by ensuring that a reasonable portion of rice production remained available for local consumption.

Evolution of MEP Over the Years

Over the last few years, the government has made several adjustments to the MEP for Basmati rice, responding to changing market conditions and stakeholder feedback.

Pre-August 2023: There was no MEP imposed on Basmati rice exports, and the market operated freely without regulatory price floors.

August 2023: The government introduced an MEP of $1,200 per metric ton. This measure was designed to combat the potential mislabelling of non-Basmati rice as Basmati and to control export volumes amid global price volatility3.

October 2023: After considerable backlash from exporters, the MEP was reduced to $950 per metric ton, which was seen as a partial concession to industry concerns about international competitiveness.

September 2024: In a significant shift, the MEP of $950 per metric ton has been removed altogether. The government claimed this would enhance India's competitiveness in global markets and boost the incomes of farmers, but concerns about the lack of price regulation persisted.

Commerce Minister's Perspective on the Decision

Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal took to Twitter to express his support for the removal of the MEP, stating:

"A big step towards farmer welfare! The decision to remove the Minimum Export Price on Basmati rice is commendable. This will increase exports and also boost farmers' income."

Goyal presented the removal as part of the government’s broader pro-farmer agenda, indicating that the change would enhance India's standing in global markets and directly benefit agricultural communities by increasing export volumes.

Sarcastic Criticism by Farmer Leader Ramandeep Singh Mann

Not all reactions were favourable. Farmer leader Ramandeep Singh Mann responded to the government’s announcement with a sharply sarcastic tweet:

"Minister sir, this Minimum Export Price on Basmati was imposed by @narendramodi ji's Government, which reduced Basmati exports, causing Basmati prices to fall and severely impacting farmers' income. You yourselves made an anti-farmer decision, harmed the farmers, and now you're patting yourselves on the back for reversing your own decision. Incredible!"

Mann’s critique points to the irony that the same government responsible for introducing the MEP—which he claims harmed farmers by reducing export volumes and depressing prices—was now positioning the removal of the MEP as a pro-farmer move. This viewpoint reflects the broader frustration of many in the agricultural sector, who see the initial imposition of the MEP as having caused more harm than good. It is also intriguing as to why this official communication, which the Commerce Minister himself shared on X, has been classified as CONFIDENTIAL, whereas it deserves wider dissemination.

Analysis: A Market Distortion from the Beginning

From a policy perspective, the MEP can be seen as a distortion of market forces. Basmati rice, unlike other staples, is largely an export-oriented crop with limited domestic consumption. As nearly 100% of Basmati production is exported, implementing an MEP essentially placed a cap on the price competitiveness of Indian Basmati in global markets. This could have led to profits being redirected from farmers to exporters, as middlemen capitalised on the price floor to boost their margins while farmers were left with lower incomes due to reduced demand.

Moreover, Basmati rice is an ideal alternative to paddy—a water-intensive crop—and has been promoted as a sustainable choice in water-scarce states like Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh. By discouraging the cultivation of Basmati through the imposition of MEP, the policy inadvertently supported the continued production of water-guzzling crops like paddy, which further strained the region’s depleting groundwater resources.

Summing Up: The Way Forward

The removal of the MEP is a welcome correction of a flawed policy that only served to constrain the export potential of Indian Basmati rice, which had been getting increasing competition from Pakistan’s produce. It is now crucial that the Government of India maintains this stance and allows market forces to drive the international pricing of Basmati, without reintroducing unpredictable regulatory measures that harm the competitiveness of Indian farmers. By sticking to this course, the government can boost Basmati exports, ensure fair pricing for farmers, and promote sustainable agricultural practices in water-scarce regions.

Going forward, the focus should be on encouraging the cultivation of Basmati as an alternative to water-intensive crops, aligning with both environmental goals and the economic well-being of farmers.4

Basmati Cultivation and Exports: The Ecology, Economics, and Politics of Punjab and the Centre

Basmati Cultivation— towards diversifaction?

SBI's Statement on MSP: Immediate Backlash from Farmer Organisations

SBI's Statement on MSP: “Ill-time and Ill-conceived”

Basmati $1200/tonne Minimum Export Price: Why is the Exporter Lobby Squeaking?

The New Basmati Export Benchmark: Unreasonable or Justified?

Export Bans on India's Agricultural Commodities: Humongous Losses to the Farmers

Main Agricultural Commodities Facing Export Bans