IAS officers: Individually brilliant but collectively mediocre

The quest to crack this apparent paradox.

Prologue

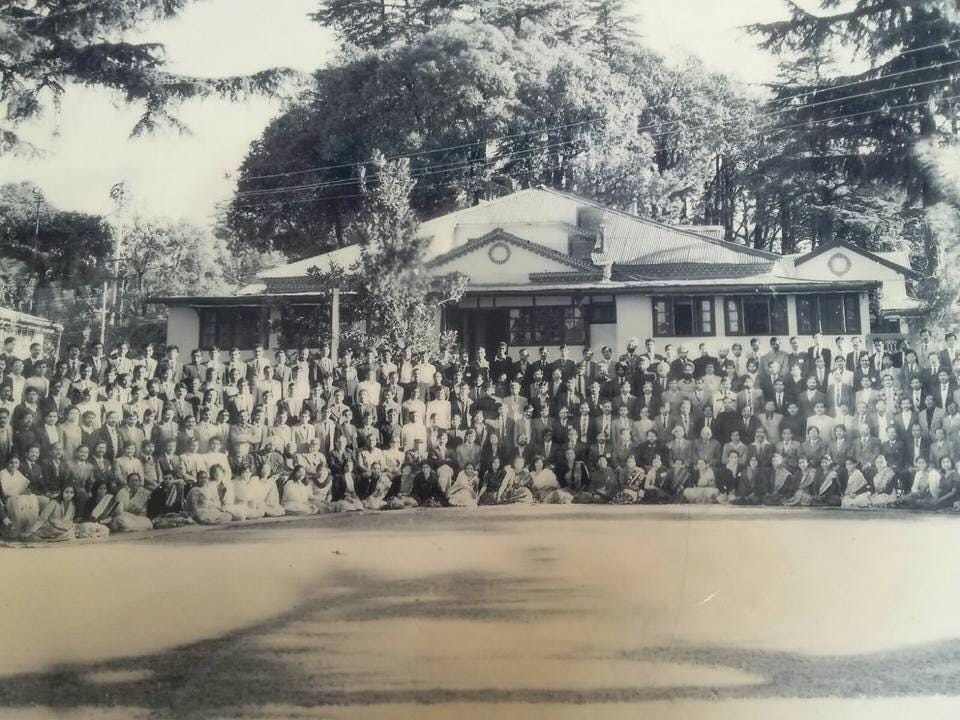

Today stands as a significant milestone — exactly 39 years since I ventured into the hallowed halls of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration in Mussoorie. That transformative day, 21st August 1984, flagged off my journey as an IAS officer, one that spanned until my superannuation in July 20211. In 2018, I put pen to paper, crafting this article to share both my experiences and inferences from the myriad nuances of the IAS.

As I revisit this piece today, I offer it with minimal refinements, inviting readers to gauge its pertinence. I encourage you to analyze and determine how relevant or justified my observations remain, especially five years down the line from its initial publication.

A dream job that converts brilliance into mediocrity?

The Indian Administrative Service (IAS) is often seen as a dream job, one that millions of young graduates ardently pursue through the annual competitive Civil Services Examination. The UPSC's rigorous and merit-driven selection process is widely lauded, and the examination stands as a testament to the "equality of opportunity" enshrined in our Constitution. Despite the influx of dedicated and talented individuals into the service year after year, the larger public perception is less flattering. While citizens and politicians might grudgingly rate the performance of the IAS as a collective at a mere "average", intellectuals, academicians, journalists, and industrialists often acknowledge an individual IAS officer's brilliance. However, the IAS as an entity is frequently painted with a broad brush as a group dominated by self-serving, career-driven, conservative, and arrogant individuals, seemingly reluctant to make bold decisions for the Nation's greater good.

Politician-Bureaucrat Nexus to Blame?

Why, then, does the IAS, with its cadre of acknowledged well-meaning and upright members, falter in meeting the expectations of its stakeholders? A prevailing theory, albeit generalized, is the existence of a symbiotic relationship between politicians and bureaucrats. In this dynamic, politicians can forward both overt and covert agendas, while IAS officers ensure their continued dominance in the top echelons of bureaucracy, both at the Centre and in the States. This often happens at the expense or even exclusion of their equally competent counterparts from other All India and Central Services. Furthermore, the IAS is sometimes perceived as an 'elite club' that lays claim to exclusive expertise, asserting proficiency in district-level executive roles and central policy specialization.

Assuming for a moment, without fully conceding, that these views hold merit, it's essential to investigate the reasons behind the IAS's collective behavior. Such exploration might help us understand the pedestrian evaluations the service receives, a feedback that, frankly, leaves much to be desired.

Incremental approach works

The IAS, whether universally appreciated or not, is inherently designed to maintain a status quo in public governance. While it's fashionable to discuss concepts like innovation, inclusion, and empowerment, the service's underlying mandate isn't necessarily to spearhead radical shifts in governance. It's no surprise then that the philosophy of "incrementalism" is commonly endorsed in various Institutes of Public Administration and Administrative Staff Colleges. Further complicating the scenario is the retrospective scrutiny executive decisions often undergo—sometimes decades later—by investigative agencies possessing the benefit of hindsight. Failures are harshly critiqued, while successes are typically met with muted acclaim, if acknowledged at all. In such an environment, it's only logical for officers to gravitate towards a cautious, conservative approach, rather than venture boldly into uncharted territories.

Free and fair advice welcome?

This dynamic is evident in the nature and quality of advice that officers record on files they submit to the political executive. Today, democratically elected ministers aren't just well-educated; they often have access to external "expert" advice, whether from formal consultants or informal advisors—a group colloquially termed the 'kitchen cabinet.' Consequently, many ministers come with a preconceived policy vision. This relegates the IAS officer's role in a secretariat or ministry to merely ushering policies through the official procedural maze to secure final approval, as per the Rules of Business. Offering a divergent perspective or highlighting potential policy pitfalls is rarely met with enthusiasm by the decision-makers. This not only fosters tension but also labels IAS officers as chronic naysayers. Yet, in a twist of irony, should a policy falter, the blame often lands at the IAS's feet, bringing potential disciplinary and criminal repercussions. To avoid this quagmire, some IAS officers opt for a more cautious approach—either soft-pedaling decisions or delaying them—further solidifying the service's perceived inefficiency. Although trained to provide objective, fair, and fearless advice, witnessing the frequent futility of such counsel prompts many officers to abandon this principle relatively early in their careers.

Standing out in the herd

How does one break free from the mold in a culture steeped in the pressure to conform? For long, civil servants have been advised to embrace anonymity, often chided for seeking the spotlight. Yet, in today's digital age, some younger, media-savvy officers are casting aside such counsel. They astutely highlight even modest achievements, amplifying them on public platforms. Examples abound: a Collector transforming a small town's sanitation, another's spouse voluntarily teaching in a neglected government school in a tribal area, or a serving Collector working incognito as a laborer in a flood-relief camp far from his jurisdiction. While the media, public, and intellectual community might laud these acts, they don't necessarily reflect systemic reforms. Seasoned officers, who might recognize these acts as clever PR strategies, often find themselves begrudgingly joining the chorus of praise. However, such publicity often serves its purpose, giving these "innovative" officers a noticeable career boost.

Anonymity is a virtue?

Every year, on Civil Services Day on 21st April, the Prime Minister’s National Awards honor innovative schemes from various states and ministries. On paper, these winning entries often seem transformative, holding the promise of nationwide impact if pursued diligently. Yet, there's a glaring absence of follow-up evaluations. It's rare for these initiatives to undergo review three or four years post-recognition, to assess their sustainability and impact. My suspicion is that many of these ideas fade away with time. This is because many of them, while commendable, are micro-initiatives. For instance, a Collector might invest a significant portion of their time and resources on a minuscule challenge and, unsurprisingly, record success. Or there could be impressive mobile apps that, despite their potential, never see widespread use. While these solutions might shine in isolation, they often stumble when it comes to scalability or nationwide replication, either due to their inherent limitations or insufficient resources.

Mutual respect is the way forward

How can we realistically expect an IAS officer to navigate the intricate web of political and bureaucratic dynamics? In an article I penned for ThePrint (link), I posited that many officers lean towards catering to the "elite" with almost a 5-star service quality, while the common citizen struggles in endless queues. This skewed prioritization may be a necessity for their professional survival. To break free from this mire, consistent dialogue is imperative—between the top political executives and the IAS officers, both at the Centre and in the States. Assurances—both verbal and demonstrated—need to be provided, ensuring officers that their commitment is genuinely appreciated. They should be reassured that they won't be subjected to unfair scrutiny for mere errors in judgment or honest mistakes. Such initiatives would expedite the journey towards achieving exemplary public governance in the Nation.

Epilogue

Despite the earnest efforts by the government to introduce "reforms" within the IAS and the broader civil services, the overarching landscape seems unchanged. The lateral entry scheme, designed to bring in professionals from varied sectors like business, industry, and academia into pivotal roles, was seen as a step forward. Yet, in reality, the changes have been mostly superficial. As the saying goes, "The more things change, the more they stay the same."

Bureaucrat, heal thyself

External reforms, though well-intentioned, can only achieve so much. True transformation can't be solely dictated from the outside; it needs to be ignited from within. This is where each IAS officer needs to turn on their "internal combustion engine" to fuel innovation, dedication, and commitment. Both serving and retired officers need to come together for introspection and collective reflection. This isn't merely about combating a flawed perception; there's a tangible reality that cannot be ignored. A genuine shift requires every officer to recognize the challenges and embrace the spirit of service more profoundly. Both as individuals and as a collective body, we owe it to our Nation to address these issues head-on, acknowledging the challenges and paving the way for meaningful transformation2.

Ohh LBSNAA! Exactly 39 years ago....

A Journey Back to the Hills of Mussoorie: Starting exactly 39 years ago. Tinge of Nostalgia August evokes a palette of emotions, not just for the ripening of monsoons or the whisper of autumn on the horizon but because it marks th…

Babu-mukt Bharat: Government of India Ministries sans IAS Officers

Prologue: In April 2019, the Government of India had introduced the groundbreaking "Lateral Entry Scheme" aimed at infusing new talent and expertise into its bureaucratic ranks, at the Joint Secretary and Director levels. The scheme allowed for the appointment of accomplished professionals from outside t…

An objective and honest assessment Sidhu ji. Enjoyed reading it💐

A brilliantly written article by a distinguished former IAS officer. He has touched upon all facets of the IAS service. It's a twist of fate that the days when idealism was the driving force for both bureaucrats and politicians have passed. Without casting aspersions on anyone, today, there's a prevalent tilt towards materialism at every echelon, with few exceptions. During the British Raj, a decree was nearly passed by the Queen to replace all the Princes (often referred to as Maharajas) with Deputy Commissioners. However, upon catching wind of this, the Princes, numbering nine, offered a substantial sum of nine lakh rupees as 'nazrana', resulting in the decision being shelved.

Now is a moment of introspection for the IAS cadre. Retired officers, perhaps forming a collective, should suggest strategies to reclaim the service's lost prestige and glory.

Dr hssidhu ias retd