Introduction

At a function organised on Saturday by the Bar Council of India, where he was sharing the stage with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud articulated a seminal point: 'While the Constitution provides for separation of powers between the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary, it also creates a space for institutions to learn from each other to deliver justice.' This emphasis on the 'spirit of collaboration' between the state's pillars is not just philosophical but immensely practical.

Adding weight to the current discourse, Vice President Jagdeep Dhankar, who is also the Chairman of Rajya Sabha, on the opening day of the recently concluded 5-day Special Session of the Parliament, called for a more transparent and accountable system of judicial appointments. Inspired by these absolutely germane and sagacious observations, this brief piece attempts to explore the complex landscape of judicial appointments in India. At the heart of this scrutiny is the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC)—a mechanism that, had it been implemented, could have served as the epitome of the institutional collaboration that Chief Justice Chandrachud spoke about.

Original Constitutional Provisions

In the foundational architecture of the Constitution of India, the prerogative for appointing judges was vested in the President, who acted in consultation with the Chief Justice of India. This constitutional mandate is encapsulated in Articles 124 and 217, specifying the modalities for the appointment of justices to the Supreme Court and the High Courts, respectively. Intended to harmonise executive authority with judicial insight, this design was reflective of the framers' aspiration for a judiciary that was both collaborative and autonomous. While the text of the Constitution has largely remained unaltered in this respect, this original scheme governed the landscape of judicial appointments in India until a tectonic shift in 1993.

Emergence of the Collegium System

The collegium system in India materialised as a judicial innovation, its roots deeply entrenched in a sequence of landmark cases commonly known as the 'Three Judges Cases.' The first of these, the S. P. Gupta case of 1982, set the stage for the judiciary's role in appointments. It was followed by the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association case in 1993, where a nine-judge bench led by Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah redefined the process. The collegium system was finally cemented by the Presidential Reference case in 1998, with a judgement penned by Justice J.S. Verma.

The system has been both celebrated and critiqued for introducing a model where "judges appoint judges," a practice that remains unparalleled globally. One of the pivotal reasons for its formation was to uphold the independence of the judiciary, considered a cornerstone of India's democratic framework. The interpretation relied significantly on the Keshavananda Bharati case of 1973, which had enshrined the doctrine that the independence of the judiciary is a part of the 'basic structure' of the Constitution and thus, not amenable to legislative amendments. Therefore, the collegium system emerged as a unique mechanism intended to safeguard judicial independence by giving the judiciary a decisive say in its own appointments.

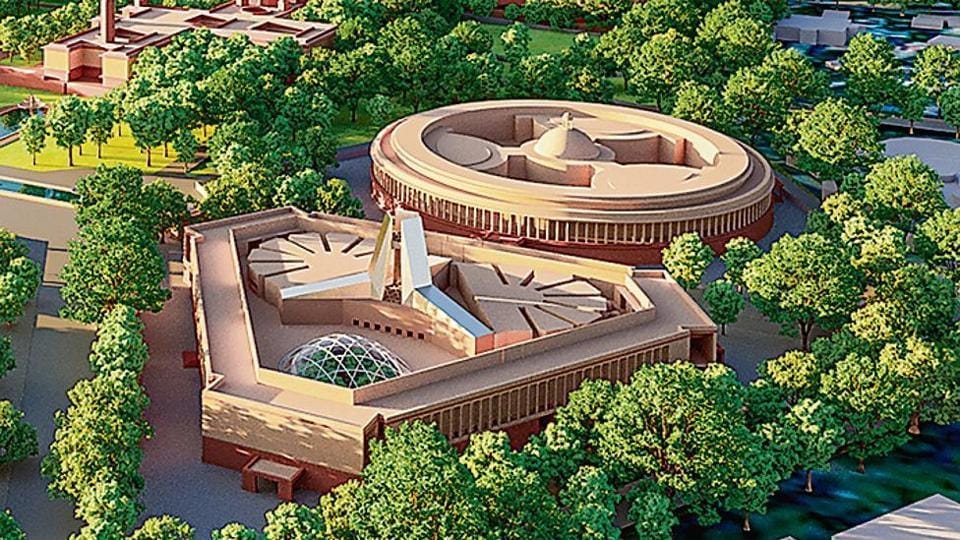

The 99th Amendment and National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC)

In 2014, the Indian Parliament enacted the 99th Constitutional Amendment with remarkable unanimity, heralding the formation of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). This groundbreaking move was perceived as an attempt to enhance transparency and infuse a sense of democracy into the judicial appointments process. The NJAC was conceptualised as a six-member body, comprising the Chief Justice of India, two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, the Union Law Minister, and two 'eminent persons' who would be nominated by a panel consisting of the Prime Minister, the CJI, and the Leader of the Opposition.

The NJAC was endowed with expansive powers and responsibilities. Not only would it recommend persons for appointment as Chief Justice of India, judges of the Supreme Court, and Chief Justices and other judges of the High Courts, but it was also granted authority to recommend transfers between the High Courts. The involvement of 'eminent persons' and a key member from the executive aimed to break the judicial monopoly over appointments, thus ensuring a balanced representation of the three pillars of democracy— the judiciary, the legislature, and the executive.

Moreover, the NJAC was entrusted with laying down the procedure for the discharge of its functions, aimed at making the appointments process more rational, accessible, and efficient. By including a diverse set of voices, it sought to remedy the opacity and exclusivity that critics argue had marked the collegium system. Therefore, the 99th Amendment and the introduction of NJAC were touted as historic milestones aimed at recalibrating the balance of power in India's judicial appointment mechanism.

Striking Down of NJAC

In a pivotal moment on 16th October 2015, a Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court, led by Justice Jagdish Singh Khehar, struck down the 99th Constitutional Amendment and the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act by a 4-1 majority. The majority judgement articulated that the NJAC had the potential to undermine the independence of the judiciary—a cornerstone considered part of the Constitution's basic structure, as reaffirmed by the landmark Keshavananda Bharati case. The court maintained that the inclusion of executive members in judicial appointments through the NJAC could imperil the judiciary's autonomy and impartiality.

This decision elicited a spectrum of reactions, including strong critiques from several political figures. Then-Finance Minister Arun Jaitley was particularly forthright, describing the verdict as representing "the tyranny of the unelected." Jaitley's remarks encapsulated the broader apprehensions about the judiciary's perceived overreach, especially in annulling a constitutional amendment that had been unanimously passed by the Parliament. These comments ignited a complex debate between the judiciary's need for independence and the principles of democratic governance—a debate that remains unsettled.

Consequently, the judgement delivered on that October day re-established the collegium system, reinstating the judiciary's exclusive role in its own appointments. It highlighted the perennial tension between the judiciary's independence and the broader framework of checks and balances, revealing the intricate and at times conflicting dynamics that shape India's democratic system.

Comparison with the U.S. System

In the United States, the system for judicial appointments functions quite differently from that of India. Judges, including those nominated to the Supreme Court, are selected by the President but must undergo a rigorous confirmation process involving the Senate. This Senate scrutiny includes public hearings, where nominees are questioned on their judicial philosophy, past judgements, and legal opinions. The system is lauded for establishing a balanced mechanism that incorporates both executive choice and legislative oversight, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of a candidate's suitability. While not without its own criticisms, such as the potential for partisan influence, the U.S. model provides an interesting contrast, particularly in its explicit incorporation of checks and balances in the appointment process.

Independence of Judiciary: Appointment, Removal and Post-retirement Assignments

Judicial independence is not solely determined by the appointment process; it is also closely tied to the mechanisms for removal. In India, impeachment of a judge requires approval from both Houses of Parliament, specifically a two-thirds majority of the members present and voting, as evidenced in the case of Justice V. Ramaswamy. This cumbersome process essentially ensures that judges can operate without undue external pressures. However, the prospect of post-retirement assignments, like heading tribunals or serving on arbitration panels, has raised ethical questions. The issue gained prominence with remarks from the late Arun Jaitley, then Leader of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha, suggesting that such assignments could potentially influence judicial decisions made prior to retirement. While the method of appointment is crucial and, when complemented by stringent removal procedures, largely secures judicial independence, the prospect of post-retirement assignments cannot be completely dismissed. Such opportunities have the potential to cast a nuanced shadow over the judiciary's independence, if not integrity

The Women’s Reservation Bill and the Lost Unanimity

The almost unanimous passage of both the 99th Amendment in 2014 and the recent Women's Reservation Bill demonstrates that there are indeed issues on which the Indian Parliament can rise above partisan politics. These milestones suggest that when the stakes are high and matters of constitutional importance or social justice are on the table, legislators are capable of coming together in a spirit of national interest. This raises hope that a similar consensus can be achieved on other pressing issues facing the country.

Looking Head with the Current Leadership: PM Modi and CJI Chandrachud

In the current landscape, Prime Minister Modi and Chief Justice Chandrachud occupy pivotal roles and have gently guided the discourse towards a broader theme of cooperation and collaboration, of which judicial appointments are undeniably a critical element. Chief Justice Chandrachud's call for "collaboration" among the three branches of governance resonates strongly, particularly as we navigate the intricacies of judicial appointments. This prompts the question of whether the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), re-envisioned, could epitomise this ethos of institutional cooperation. Building on this, PM Modi has an opportunity to foster consensus—be it formal or informal—around this crucial matter, inviting an all-encompassing review. While the path ahead is fraught with complexities, it remains essential to safeguard the inviolability of judicial independence and integrity. Upon rigorous examination, if we renew our allegiance to the Collegium system, acknowledging its imperfections but deeming it the most viable option, then the dialogue still warrants a holistic and cooperative re-evaluation.

![NJAC Unconstitutional ; Constitution Bench [4;1] [Read Judgment] [Updated] NJAC Unconstitutional ; Constitution Bench [4;1] [Read Judgment] [Updated]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6Zd-!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F758cfc22-55de-47f4-a336-34bf327d82ef_842x486.jpeg)

Every article looks meticulously researched and fine tuned, with catchy anecdotes here and there! Good job 👍

Well articulated view. Independent judicial appointment process is as important as independence of judiciary.