General Musharraf's Baghpat Bungalow to Jinnah House in Bombay: Legendary Litigious Legacies.

The Misconceptions About Evacuee Property and Application of the Displaced Persons (Compensation and Rehabilitation) Act of 1954.

The Curious Case of Parvez Musharraf’s Ancestral Home

Recently, a news headline declared, "Former Pakistani Army Chief Parvez Musharraf's ancestral property in Uttar Pradesh's Baghpat will be auctioned." This statement, however, is misleading and reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the status of properties left behind by those who migrated to Pakistan during the Partition in 1947. The reality is that once the original owners left India for Pakistan, such properties were classified as "evacuee properties." These properties were not left in limbo but were instead vested in the Central Government under the Displaced Persons (Compensation and Rehabilitation) Act of 1954. This law was pivotal in addressing the massive displacement and ensuring the structured allocation and management of properties abandoned during the Partition.

Understanding the Concept of Evacuee Property

To understand why the headline about Musharraf’s ancestral home is misleading, it's important to explain the concept of evacuee property. General Pervez Musharraf, who passed away on February 5, 2023, at the age of 79 in Dubai, was only indirectly and merely notionally connected to the Baghpat property that has been in news recently. During the Partition of India in 1947, millions of people migrated across the newly drawn borders between India and Pakistan, leaving behind their homes and communities. To manage these abandoned properties, the Indian government classified them as "evacuee properties." This designation was meant to prevent unauthorized occupation and ensure proper management during the tumultuous period following Partition, placing these properties under government control to be used for rehabilitation and other official purposes.

The Displaced Persons (Compensation and Rehabilitation) Act, 1954, was enacted to manage these properties and provide compensation and rehabilitation to those who had been displaced from Pakistan. This law ensured that properties left by those who migrated to Pakistan were legally taken over by the government, which could then use them for the rehabilitation of refugees or other public purposes. Consequently, Musharraf’s ancestral property in Baghpat is not privately owned by his family but is, in fact, a government property, managed as per the legal frameworks established post-Partition.

Pervez Musharraf's Birth and Family Background

Pervez Musharraf was born on August 11, 1943, in Delhi, British India, to an Urdu-speaking Muslim family. Before the Partition of India in 1947, Musharraf's family lived in a large home in Delhi known as "Nehar Wali Haveli," which translates to "House Next to the Canal." His father, Syed Musharrafuddin, was a civil servant who worked in the foreign office of the British Indian Government, while his mother, Begum Zarin Musharraf, was raised in Lucknow. The family had a strong lineage of government service, with his great-grandfather serving as a tax collector and his maternal grandfather as a qazi (judge). In August 1947, just days before the partition and the subsequent independence of India and Pakistan, Musharraf’s family migrated to Karachi, Pakistan. At the time of this move, Musharraf was four years old. His family's migration marked a significant transition from their established life in Delhi to starting anew in the newly formed Pakistan.

The Significance of Avoiding Waqf Status

One could argue that India’s handling of evacuee properties has avoided significant complications, particularly when compared to other historical instances of abandoned properties in conflict zones. An important consideration here is the distinction between evacuee properties and those that might have been declared waqf properties. A waqf property is one that is donated for religious or charitable purposes under Islamic law, and its management can be subject to various interpretations and disputes over religious ownership and use.

Had properties like Musharraf's ancestral home been declared waqf— even if wrongly— it could have led to complex legal battles over religious endowments and community rights, further complicating an already sensitive situation. Instead, by clearly categorising these properties under the Displaced Persons Act, the Central Government as well as the Uttar Pradesh Government avoided additional layers of dispute, allowing for more straightforward legal administration.

The Pitfalls of Allotting Properties at Throwaway Prices

The process of rehabilitating displaced persons involved a careful allocation of properties and resources. However, the notion of allotting valuable properties at throwaway prices has been a point of contention. While it was necessary to provide shelter and means of livelihood to millions who had lost everything, there were instances where prime properties were handed over at minimal costs. This practice, though perhaps well-intentioned, sometimes led to allegations of unfair advantage and corruption, stirring controversy and dissatisfaction among those who felt wronged by the process.

This historical context is vital when considering current debates around properties especially those like Jinnah House in Mumbai, which also falls under the category of evacuee property. The Indian government’s decisions in managing these properties reflect not just legal considerations but the socio-political complexities of a post-Partition India.

Veering into the Controversy Surrounding Jinnah House

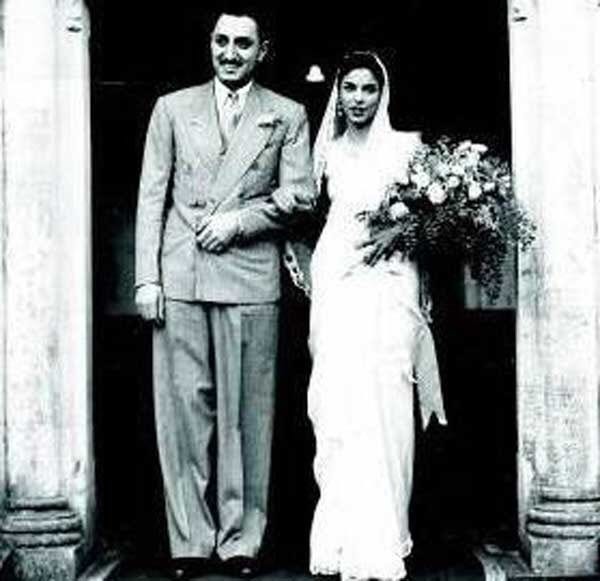

This brings us to the ongoing debate surrounding Jinnah House, a grand sea-facing bungalow in Mumbai's upscale Malabar Hill area, built by Muhammad Ali Jinnah in 1936. Like Musharraf’s ancestral property, Jinnah House became an evacuee property after Partition. However, unlike the relatively straightforward situation in Baghpat, Jinnah House has been a focal point of diplomatic tensions between India and Pakistan.

Jinnah House: A Symbol of Historical Significance and Diplomatic Dispute

Jinnah House, an opulent sea-facing bungalow situated on 2.5 acres in the prestigious Malabar Hill area of Mumbai, is more than just a piece of prime real estate. It stands as a poignant symbol of the tumultuous history of the Indian subcontinent, a witness to the Partition of India in 1947, and a centrepiece in the ongoing diplomatic tussle between India and Pakistan, apart from protracted litigation between the Central Government and private claimants.

The Origins and Architectural Grandeur of Jinnah House

Built in 1936 by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, arguably the architect and founder of Pakistan, Jinnah House represents a significant piece of history intertwined with the life of one of the most influential figures of the 20th century in the history of South Asia. The bungalow was designed by the renowned architect Claude Batley, who gave it a distinctive European style that blends Italian marble and exquisite walnut woodwork. Constructed at a cost of Rs 2 lakh—a princely sum at the time—Jinnah House was more than just a residence; it was a statement of affluence and taste.

The Ownership Controversy: A Tale of Claims and Counterclaims

The ownership of Jinnah House has been mired in controversy since the Partition of India in 1947. Following Jinnah’s migration to the newly formed Pakistan, the Indian Government took control of the property, classifying it as "evacuee property." This move has been the foundation of a protracted legal and diplomatic dispute.

Pakistan has repeatedly requested for the ownership of Jinnah House, proposing to use it as its consulate in Mumbai. However, the Indian government has consistently rejected these claims, maintaining that the property legally belongs to India. The issue took a more personal turn in 2007 when Dina Wadia, Jinnah’s daughter, filed a petition in the Bombay High Court asserting her right to the property as Jinnah's legal heir. Her claim added a new dimension to the dispute, bringing in personal and emotional elements to an already complex issue. Additionally, two Mumbai residents have also laid claims to partial ownership, further complicating the matter.

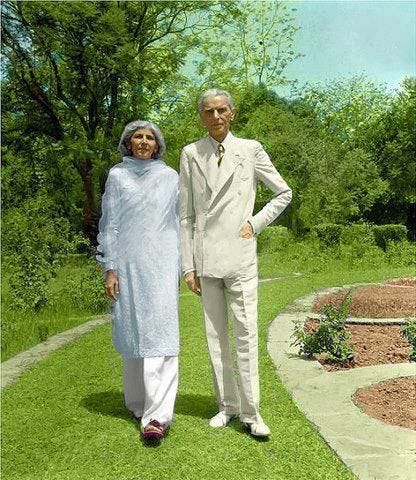

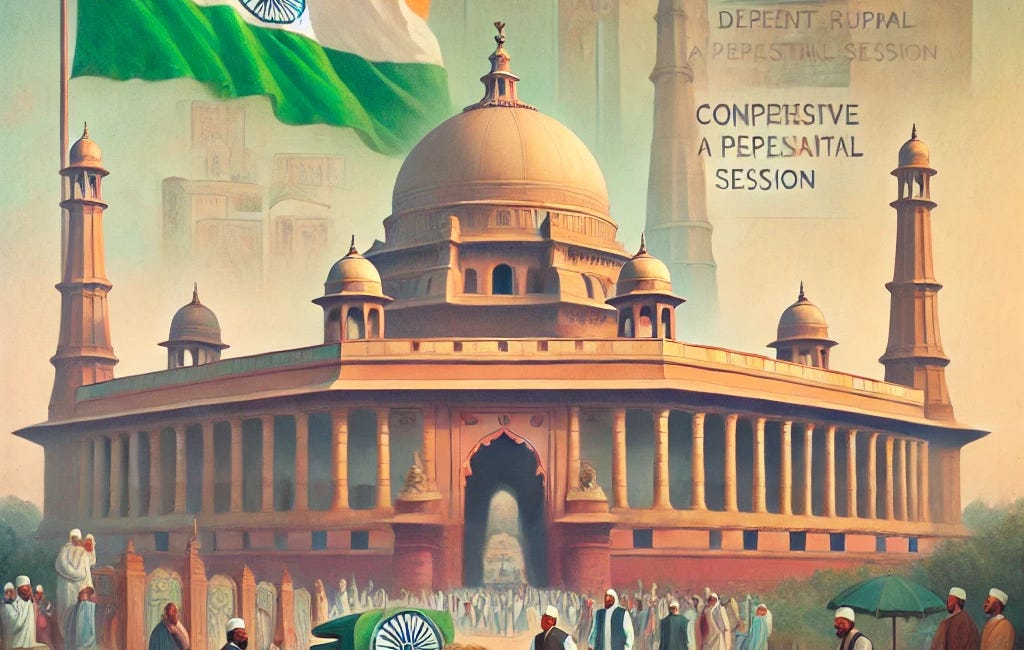

Dina Wadia's Marriage and Its Impact on Her Relationship with Jinnah

Dina Wadia married Neville Wadia, currently the Chairman of Bombay Dyeing, one of India's leading textile companies, in 1938. Neville, originally born into the Parsi community, had converted to Christianity prior to their marriage, a decision that deeply troubled Dina's father, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Jinnah strongly opposed the union, primarily because Neville was not a Muslim. When Dina pointed out that her mother had also been a Parsi, Jinnah retorted that she had converted to Islam for their marriage. This disagreement over her marriage choice led to a strained relationship between Dina and her father, marked by limited contact through letters and occasional meetings. The marriage itself was short-lived; Dina and Neville separated in 1943, just five years after their wedding, although they never formally divorced. The couple had two children, Nusli Wadia, who would go on to become a prominent industrialist, and a daughter, Diana.

Dina Wadia’s Claim as the Daughter of Jinnah

Dina Wadia's claim to Jinnah House is rooted in several key arguments. As Muhammad Ali Jinnah's only child and daughter, she asserted her position as his sole legal heir. Wadia challenged the validity of Jinnah's will, which allegedly bequeathed the property to his sister Fatima, on the grounds that it was never probated by the Bombay High Court and thus held no legal effect. She argued that she should inherit the property under two possible legal frameworks: Hindu Law, which was applicable to the Khoja community to which Jinnah belonged before Independence, or Shia Muslim Law. Additionally, Wadia contended that Jinnah House could not be classified as "evacuee property" because her father died without leaving a valid will. She also expressed a personal desire to spend her remaining years in the house where she spent her childhood.

The reference to the Khoja Muslim community of Gujarat is significant as it highlights the community Jinnah was a part of before Independence, which traditionally followed Hindu personal laws. Wadia used this as a basis to argue that under the legal framework that would have applied to Jinnah's estate at the time of his death, she was entitled to the property.

Legal Battles and Diplomatic Stalemate

The legal status of Jinnah House remains unresolved, with Dina Wadia's petition still pending in the Bombay High Court. The Indian government continues to assert its ownership, while Pakistan persists in its demand, creating a diplomatic impasse that reflects the broader tensions between the two nations. Despite Pakistan’s request, India has categorically stated that Pakistan has no locus standi regarding the property, thus rejecting any notion of transferring the bungalow to Pakistani control.

The Current State of Jinnah House

Today, Jinnah House stands unoccupied and in a state of disrepair, a stark contrast to its former grandeur. The once-luxurious bungalow is under the control of India’s Ministry of External Affairs, which has announced plans to renovate it. There have been discussions about transforming the property into a venue for government events, reflecting India’s intent to retain control and repurpose the space for its own diplomatic and cultural functions.

Recent Developments: Proposals for the Future

In recent years, several proposals have emerged regarding the future of Jinnah House. In 2018, there was a suggestion to convert the bungalow into a South Asia Centre for Arts and Culture, which could serve as a neutral ground for cultural exchange between South Asian countries. This idea, however, has not materialised, leaving the future of Jinnah House uncertain. Meanwhile, BJP MLA Mangal Prabhat Lodha has repeatedly advocated for demolishing the structure and replacing it with a cultural centre that reflects Indian heritage and values.

A Property Entangled in History, Litigation Diplomacy

The saga of Jinnah House is far from over, as this dispute goes beyond mere real estate and reflects the enduring complexities of India-Pakistan relations. The bungalow serves as a silent witness to the historical events that have shaped the subcontinent, remaining a contentious issue in the diplomatic dialogue between the two nations. Despite ongoing legal proceedings and various proposals for its future, Jinnah House continues to symbolize the unresolved issues of Partition—a lingering reminder of a history that refuses to fade away. Although Dina Wadia, who fought for ownership of the property, passed away on November 2, 2017, at the age of 98 in her home in New York City due to pneumonia, the matter is still being pursued by her legal representatives, who claim to have stepped into her shoes.

Our view, however, is unequivocal: once Mohammad Ali Jinnah chose Pakistan during his lifetime and migrated to the nascent nation permanently, any questions of his succession after his death are irrelevant, and this prime property rightfully vests in the Central Government, free from all encumbrances. It is a a sad reflection on the Indian legal system that a dispute based on a straightforward question of law—where the facts are undisputed—has yet to be authoritatively resolved, leaving this heritage property to deteriorate and verge on becoming ruins.

The Broader Implications of Property Management Post-Partition

The cases of General Musharraf’s ancestral property and Jinnah House highlight the complexities involved in managing properties left behind during the Partition. They serve as reminders of the extensive socio-political and legal challenges that emerged in the aftermath of one of the largest migrations in human history.

The Displaced Persons (Compensation and Rehabilitation) Act of 1954 was a response to these challenges, providing a legal framework that aimed to balance the needs of the displaced with the imperative of maintaining order and fairness. While the administration of evacuee properties has not been without controversy, it has largely been guided by principles of law and equity, avoiding potential pitfalls such as religious disputes or the undervaluing of prime real estate.

In Summary: The Need for Accurate Representation and Historical Context

The misleading headline regarding General Pervez Musharraf’s ancestral home underscores the importance of accurate representation and understanding of historical context. Properties like General Pervez Musharraf's home in Baghpat and Jinnah House in Mumbai are not just real estate assets; they are intertwined with the complex histories and enduring legacies of Partition. Their management reflects not only legal ownership but also the socio-political imperatives of a nation striving to reconcile its past with its present1.

As such, it is crucial to approach these topics with a nuanced understanding that recognises both the historical significance and the legal frameworks that govern them, ensuring that discussions are informed by facts rather than misconceptions2.