Forest Laws Amendment of 2023: Progressive or Perverse Legislation?

The Forest Conservation (Amendment) Act, 2023— the rationale, salient features, impact and criticism.

The Forest Conservation (Amendment) Act, 2023

The Forest Conservation (Amendment) Act, 2023, received the assent of both Houses of Parliament during the last monsoon session. It was granted Presidential assent and published in the Official Gazette on 4th August 20231. The Act's provisions will be enforced on a date to be notified in due course2.

Points of Contention: Debates in Parliament and Beyond

As the Bill underwent scrutiny in both Houses of Parliament and the Joint Parliamentary Committee, pro-conservation groups raised concerns. They argued that the amendment would weaken the original Forest (Conservation) Act of 1980 and nullify the Supreme Court's landmark Godavarman verdict from 12th December 1996. Critics further warned that the amendments could open the virgin forests of the northeast to commercial exploitation, affecting both the ecology and socio-economic fabric of the region.

Counterpoint: The 1980 Act's Shortcomings

Conversely, some argued that the original 1980 Act was hastily enacted during Mrs Indira Gandhi's tenure to centralise the powers of forest conversion from State Governments to the Central Government. The Act was criticised for its ambiguity, as it didn't formally define the term "forest," leading to unending litigation. The process for converting forest to non-forest use was so stringent that it hindered basic activities like creating access roads, even if it involved felling a few trees on public land. Everything required the prior approval of the Central Government or its mofussil offices.

A Judicial Perspective: The Godavarman Case

Pro-conservation activists argue that any gaps present in the Forest (Conservation) Act of 1980 had already been comprehensively addressed by the Supreme Court's landmark Godavarman case. The case, which issued its core verdict on 12th December 1996, operates under the framework of a continuing mandamus. This implies that the Apex Court continues to monitor the situation, making it redundant to introduce new amendments that risk diverting scarce forest areas for non-forest uses.

Before delving further into the implications of the new amendments, it is pertinent to understand the key features of the Godavarman case.

Salient Features:

1. Broad Interpretation of Forests: One of the key features was the court's broad interpretation of the term "forest." The Court held that the term should be understood according to its dictionary meaning, thereby covering all statutorily recognised forests, whether designated as national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, reserved forests, or even private forests.

2. Regulation of Non-Forest Activity: The judgement curtailed the diversion of forest land for non-forest purposes without prior approval from the Central Government, in accordance with the Forest (Conservation) Act of 1980.

3. Centrality of Sustainable Development: The case highlighted the importance of sustainable development and the principle of inter-generational equity in natural resource management.

4. Appointment of Committees: Various committees and authorities, such as the Central Empowered Committee (CEC), were established to oversee the implementation of orders, thereby institutionalising the Court's supervisory role.

5. Stoppage of Illegal Activities: The Court ordered the cessation of all illegal mining, including “non-forest” activities, and the removal of encroachments in forest areas.

6. Afforestation Funds: Through this case, the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA) received legal recognition. Funds collected under CAMPA were intended to be utilised for afforestation and wildlife protection measures.

7. Ongoing Mandamus: The case remains open, and the Court continues to issue orders and directives to various State Governments and their agencies to ensure compliance with its rulings.

8. Empowerment of Local Communities: While not directly part of the original case, subsequent rulings and guidelines were issued by the Court to ensure the inclusion and involvement of forest-dwelling and tribal communities in conservation efforts, though this aspect remains controversial.

Criticism and Praise: Godavarman's Legacy

On one side, the judgement has been lauded for its comprehensive approach towards forest conservation and for bringing forest-related issues into the limelight. Critics, however, argue that the judgement has sometimes been implemented in a manner that disadvantages indigenous and local communities who are dependent on forests for their livelihoods.

In our view, the Godavarman case serves as an essential legal framework for forest conservation in India. However, the implementation process should be refined to balance environmental protection with the needs and rights of forest-dependent communities, and the 2023 amendments are precisely a step in that direction.

An Eco-Friendly Approach: The 2023 Amendment

Critics of both the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, and the Godavarman Case argue that they hinder eco-friendly activities that are globally accepted. This sets the context for the Forest Conservation (Amendment) Bill, 2023, which has now become a law.

The Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act, 2023: Key Features

Activity Restrictions and Expansions

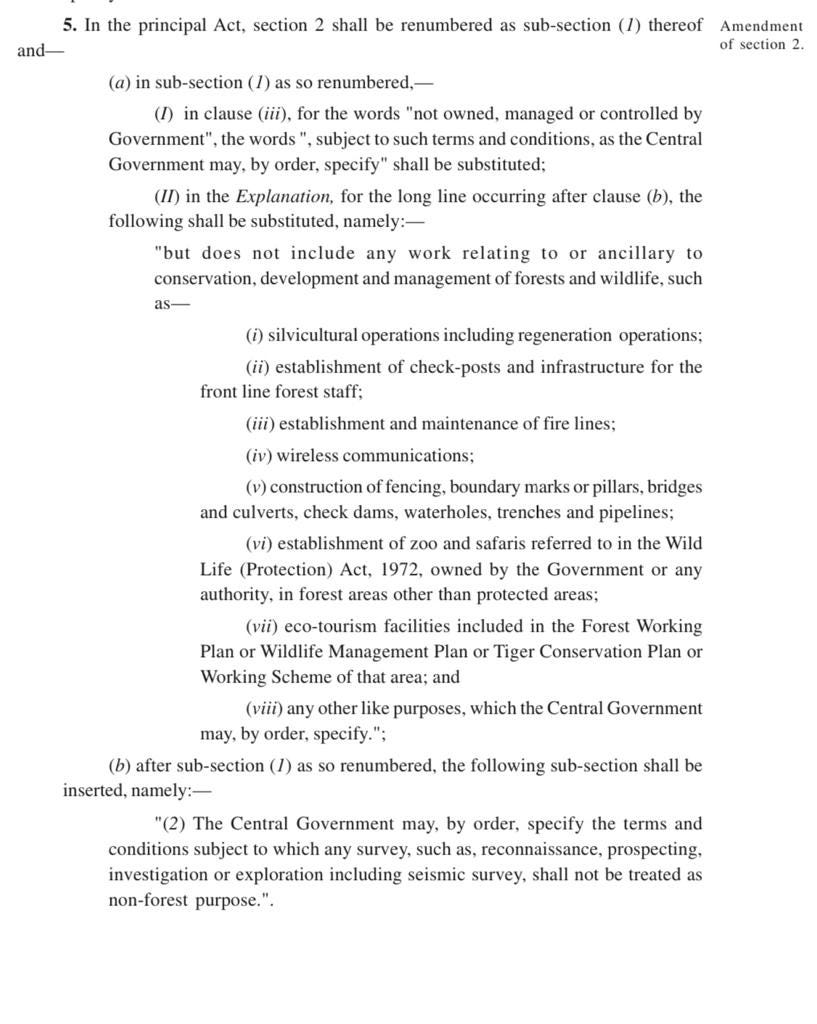

The Act primarily restricts the de-reservation of forest land for non-forest uses, unless approved by the Central Government. However, it expands permissible activities to include government-owned zoos, eco-tourism facilities, silvicultural operations, and more. We place below the screenshot of the most relevant provision of Amendment Act, as extracted from the Official Gazette.

Land Under the Act

Two categories of land fall under the purview of this amendment Act: those declared as forests under pre-existing legislation, and lands designated as forests post-October 25, 1980. However, the Act excludes lands whose use was permitted to change from forest to non-forest purposes prior to December 12, 1996, the date of the Godavarman verdict, from the scope of the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, as amended to date.

Exemptions

The Act exempts specific land categories, such as those along rail lines, international borders, and areas for national security projects. These exemptions are subject to government guidelines.

Lease Assignments

The Act requires Central Government approval for leasing forest land to non-government entities, with conditions prescribed by the central government.

Regulatory Power

The Central Government gains the authority to issue implementation directions to State Governments and Union Territories and various other entities under its jurisdiction.

Balanced Progress: The Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act, 2023

Progressive Enabling Provisions

The recent amendments to the Forest Conservation Act offer a balanced approach to forest management. They streamline the approval process for eco-friendly and nationally critical activities like defence roads, especially in sensitive border areas with China and Burma. This strikes a progressive note, freeing up projects from prolonged bureaucratic inertia.

Countering Ecological and Criminal Pressures

These changes maintain the forest's ecological integrity, resisting pressures from illegal land and forest exploitation. It's a significant shift that aligns conservation with responsible development.

Economic Opportunities, through eco-tourism, and Legal Clarity

Specifically, the new provisions open doors for eco-tourism, benefitting both tribal and non-tribal forest inhabitants. Also, by grandfathering activities permitted before the Supreme Court's landmark Godavarman case verdict on 12th December 1996, the amendments avoid retrospective punitive actions, thereby offering legal clarity.

Urgent Implementation Needed

While environmental groups are lobbying to defer the implementation, it's imperative that these enabling provisions come into effect immediately. This is especially crucial for Punjab, where outdated laws like the Punjab Land Preservation Act, 1900 have impeded eco-friendly developments, especially in the “backward” kandi areas falling in the sub-mountainous zone of the shivalik hills.

Earth as Our Shared Home

Considering Earth as our only viable home, the August 2023 amendments strike a harmonious balance between conservation and development. They allow for a coexistence of diverse ecosystems and human activity, especially in ecotourism, directly benefitting those living near forests. Therefore, the law should be enforced without further delays.

=======================================================================

Epilogue— Judicial Challenge in the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court on Friday (October 20, 2023) issued notice on a plea challenging the constitutionality of the recent amendments to the Forest (Conservation) Act.

A bench of Justices BR Gavai, Aravind Kumar, and Prashant Kumar Mishra was hearing a writ petition filed by retired civil servants, including a former secretary and an additional secretary to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC). Also among the petitioners are five former principal chief conservators of forests and ex-members of a standing committee of the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL).

The petitioners have contested the constitutionality of the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act, 2023, citing concerns that the new law would significantly undermine the country’s long-standing forest governance framework. They have said that the amendment represents a ‘complete dereliction of duty’ imposed on the State to protect and improve the environment. Accordingly, emphasising the adverse implications of the amendments on the environment, biodiversity, and climate resilience on the one hand; and the constitutional imperatives enshrined in Articles 14, 21, 48A, 51(c), and 51A(g) of the Constitution on the other hand, the petitioners have asked for the impugned amendment act to be invalidated. In support of their contention that the recent amendments ought to be set aside, they have also invoked several seminal principles of Indian environmental law, such as precautionary principle, intergenerational equity, principle of non-regression and public trust doctrine, all of which have allegedly been overlooked.

The 2023 Amendment Act, it has been contended, restricts the scope of the Forest (Conservation) Act 1980 by effectively altering the definition of forest land that falls within its purview. Such a change, according to the petitioner, contravenes the principles set forth by the Supreme Court in its 1996 order in TN Godavarman Thirumulpad. This is an omnibus forest protection matter in which the court issued the longest-standing continuing mandamus in the field of environmental litigation. Since 1996, when the writ jurisdiction of the court was first invoked by a plea to protect the Nilgiris forest, numerous orders have been passed on a vast array of issues, such as deforestation, logging, mining, compensatory afforestation, and endangered species.

The former civil servants have further argued that the amendments allow for exemptions for various projects and activities in forest lands, potentially serving commercial interests at the expense of the broader public welfare. The petition states –

“In the [1996] order, the court held that the aim of the Forest (Conservation) Act is to protect against ecological imbalance which would necessarily require ‘forest land’ in Section 2 of the act to include not only forests as understood in the dictionary sense but also any area recorded as forest in the government record irrespective of the nature of ownership or classification. Forest lands which until recently enjoyed the protection of law due to this expansive interpretation provided by this court will now be stripped of any legal protection. The 2023 Amendment Act arbitrarily permits several categories of projects and activities in forest land, while exempting them from the purview of the Forest (Conservation) Act. These projects and activities are vaguely defined in the impugned law, and could be interpreted in a manner that serves vested commercial interests, at the cost of much larger public interest.”

Each diversion of land without any cumulative ceiling being prescribed across the country, the petitioners have further argued, will ‘pockmark’ our forests with cancerously growing deforested islands and fragment them, causing enormous ecological loss. They have also raised concerns over the ‘vagueness’ surrounding project definitions and the potential for large-scale destruction of forest lands. To illustrate their contention, the petitioners have referred to provisions pertaining to security-related infrastructure, plantations, and reforested areas.

Apart from this, the former civil servants have expressed reservations about the delegated legislative powers granted to the government under the amended act, insisting that the absence of adequate guidelines for exercising such discretion could facilitate forest land diversion without appropriate regulatory oversight.

Notably, the petitioners have also called into question the rigour of the pre-legislative consultation process, alleging that a joint committee of parliament entrusted to review the legislation disregarded crucial evidence and overlooked critical concerns voiced by various stakeholders –

“The joint parliament committee repeatedly overlooked the lack of evidence to support the need for the amendment, completely disregarded the concerns and suggestions put forth by different stakeholders, and blindly accepted submissions made by the MoEFCC. The ministry, as it appears from its submissions – many of which were vague and evasive – based its decisions on the goal of facilitating ‘ease of business’ for those with commercial interests, and this unfortunately appears to be the raison d’être of the impugned legislation.”

Additionally, concerns were raised about the parliamentary committee accepting ‘at face value’ an assurance made by the environment ministry that all categories of forests defined by the state expert committees constituted in terms of the Supreme Court’s 1996 order would be given protection, without assessing the state expert committee reports. The petitioners have, in this connection, advocated for a ‘Brandeis brief’ approach with the goal of outlining the actual or probable social effects of legislation, especially because the damage caused to the environment by a ‘constitutionally deficient’ legislation would be irreversible. The petition states –

“These reports would have provided crucial information about the location and nature of forest lands across the country. However, little information about these state expert committees and their reports is available in the public domain. It is not known whether these SECs were even formed in all states; how many reports were submitted; and what is the quality of these reports. Yet, the MoEFCC places reliance on them, and the JCP accepts their existence and content without question.”

In conclusion, the petitioners have argued –

“India is one of the most vulnerable countries to impacts of climate change, and weakening its ecological security by permitting rampant deforestation will only worsen the country’s adaptive capacity. India’s forests are a crucial defence against the climate crisis. Significantly, it is now established that the carbon sequestration potential of natural forests is 40 times greater as compared to plantations, and therefore we as a country cannot afford to lose our natural carbon sinks as the alternatives such as plantations are evidently not as effective. A law that is so manifestly arbitrary in its scope, blatant in its intent to circumvent the interpretation of the law as adopted by this court, and will likely endanger ecological and food security of the country must be struck down.”

Case Details

Ashok Kumar Sharma, IFS (Retd) & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. | Writ Petition (Civil) No. 1164 of 2023.

Amendment Comes into Force from 1st December, 2023.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1EBB7T3kDgslQiZjRzzoc2Tm85GB6kRc7/view?usp=drivesdk

This amendment shall come into force from 1st December, 2023.