Evolution of the SGPC

SGPC: A Century of Stewardship and Challenge

The Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) has long stood as a beacon of resilience and dedication within the Sikh community, ardently protecting their religious heritage and managing sacred spaces. From its inception in the early 20th century, the evolution of the SGPC spans significant periods of challenge and transformation—from its foundational years under British colonial rule, through the transformative post-Independence era, the reorganization of Punjab in 1966, to the tumultuous events of 1984. This enduring journey, which extends to the present as we anticipate the next election of its General House since 2011, underscores the SGPC's crucial role in shaping the Sikh diaspora and the broader Sikh psyche, especially as the state of Haryana has been excised from its jurisdiction.

The Rise of the Akali Movement

The early 1920s heralded a crucial period in Sikh history with the emergence of the Akali Movement, a response to the need for reclaiming the sanctity of historical Sikh Gurdwaras. Key religious sites such as the Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple) Amritsar and Nankana Sahib, now in Pakistan, had come under the control of hereditary Mahants and British-appointed managers. The widespread corruption and mismanagement by these custodians led to the palpable degradation of these sacred spaces, characterized by misappropriation of funds, the introduction of non-Sikh practices, and a general neglect of core Sikh traditions.

Catalysts for Change: Corruption and Outrage

The situation at Nankana Sahib, the revered birthplace of Guru Nanak, reached a critical juncture due to the egregious mismanagement by Mahant Narayan Das. The Gurdwara was subjected to reprehensible activities that starkly conflicted with Sikh ethics. This blatant disregard for the sanctity of the site and the exploitation of religious spaces ignited widespread indignation among the Sikh community, setting the stage for a determined reform movement.

Mobilization and the Struggle for Reform

The Akali Movement rapidly gained momentum, drawing significant support from the broader Sikh community, especially from rural adherents deeply affected by the desecration of their spiritual heritage. The movement's strategy was firmly rooted in non-violent resistance, featuring peaceful demonstrations and religious assemblies. These efforts were focused on ousting the corrupt Mahants and restoring Panthic (community) control, highlighting a unified commitment to safeguarding their sacred traditions.

Key Confrontations and British Involvement

The Nankana Sahib Massacre

Despite its peaceful beginnings, the Akali Movement faced brutal violence during the Nankana Sahib Massacre in February 1921. Approximately 200 Sikh reformers were mercilessly killed by Mahant Narayan Das and his associates. This tragic event deeply galvanized the Sikh community, highlighting the dire need for substantial reforms.

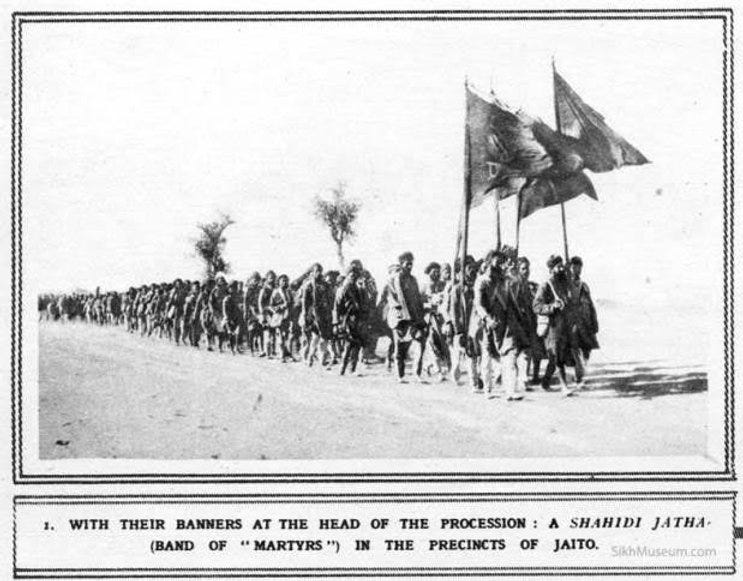

Jaito ka Morcho

The struggle for control over Sikh religious sites further escalated with the Jaito ka Morcha (campaign) in 1923, which was aimed at reclaiming Gurdwara Gangsar, near Jaito, in the erstwhile Princely State of Nabha. The British authorities' prohibition of prayer assemblies at Jaito led to violent confrontations, underscoring the colonial government's repressive measures against the movement. During this period, the movement also received notable support from the Indian National Congress, exemplified by Jawaharlal Nehru's involvement, which led to his detention by British forces, symbolizing broader political solidarity with the Sikh cause.

Legislative Triumph of the Akali Movement

The Akali Movement's unyielding efforts culminated in the passage of the Sikh Gurdwaras Act in 1925, a landmark legislative achievement that shifted control of historical Sikh shrines to the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC). This legislative success marked a pivotal moment for the Sikh community, as it aligned the management of their sacred sites with their deeply held religious and ethical values. Importantly, this ensured the preservation and protection of their spiritual heritage under their autonomous governance. This was particularly significant given the colonial rulers' marked reluctance to endorse any institution that could embody democratic governance as a foundational principle.

Legacy of the Akali Movement: Guiding Future Reforms

The historical achievements of the Akali Movement have established a robust foundation for ongoing and future reforms within the Sikh community. As we look forward, the insights gained from this critical era continue to shape the governance of Sikh institutions, ensuring they adapt to meet the evolving spiritual and communal needs of Sikhs around the world. This enduring legacy of reform serves as a blueprint for future generations, empowering them to advocate for and implement changes that preserve the sanctity and significance of their religious practices.

Legislative Journey of the Sikh Gurdwara Act of 1925

The Sikh Gurdwara Act of 1925: A Milestone in Sikh History

The Sikh Gurdwara Act of 1925 stands as a pivotal milestone and a turning point in Sikh history, realized after extensive consultations and negotiations involving Sikh reformers, the British government, and other key stakeholders. The active involvement of Malcolm Hailey, the Governor of Punjab, proved essential; he played a critical role in facilitating the drafting of the Gurdwara Bill. His engagement with key Sikh representatives, some of whom were imprisoned at the time, underscores the complexity of the political landscape during this period. This act not only marked a significant legislative achievement but also reflected the intricate interplay of power, diplomacy, and community aspirations.

Drafting and Revisions

Significant figures like Master Tara Singh, the leading Sikh leader of the time, and others played a vital role in meticulously reviewing and revising the draft legislation. Their contributions ensured that the final Bill reflected the needs and aspirations of the Sikh community. Despite the Bill's initial approval in 1922, its implementation stalled due to opposition within the Sikh community, illustrating the importance of consensus in legislative processes.

Enactment and Implementation

Introduced by Tara Singh in 1925 during a special session in Shimla, the Bill underwent further scrutiny by a select committee, which reflects the legislative diligence of the period. The unanimous passage of the Bill in the Punjab Legislative Council and its subsequent assent by the Governor General underscore the collaborative effort between the Sikh leadership and colonial authorities to rationalise institutionalise the management of Sikh Gurdwaras.

Territorial and Administrative Scope

Initially applicable to the Punjab province under British rule, the Act’s jurisdiction expanded post-independence to cover multiple regions, including Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, and Chandigarh. This expansion reflects the growing significance and outreach of the SGPC in the governance of Sikh affairs.

Electoral and Administrative Milestones

The first elections under the Act in 1926 marked the beginning of a new era in Sikh administrative autonomy. The leadership of influential presidents like Baba Kharak Singh and Master Tara Singh during the formative years of the SGPC was instrumental in stabilizing and strengthening the institution.

Defining Sikh Identity

The original Act's definition of a Sikh was pivotal in formalizing the religious identity within the legal framework, which was crucial for ensuring the integrity of the electoral process for the SGPC1. The amendment in 1945 further refined this definition, adapting to evolving interpretations of Sikh identity.

Future Perspectives on Reform

The historical context of the Sikh Gurdwara Act of 1925 set the stage for ongoing discussions about potential reforms within the SGPC. The Act not only consolidated Sikh administrative control over their religious sites but also established a model for religious community governance that could inspire future legislative improvements and reforms.

The SGPC's Influence in Post-Independence Punjab Politics (1947-1966)

Leadership and Governance

The Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) continued to play a pivotal role in the Sikh community and the broader political landscape of Punjab during the transformative years following India's Independence. Under the leadership of notable presidents like Master Tara Singh, who served multiple terms between 1947 and 1962, and Sant Chanan Singh from 1962 to 1972, the SGPC was instrumental in guiding Sikh political and religious affairs during a period of upheaval and significant change.

SGPC Elections and Democratic Participation

The SGPC elections, held periodically as per the Sikh Gurdwaras Act of 1925, were a cornerstone of democratic practice within the Sikh community. These elections ensured community participation in the management of gurdwaras and continued to reinforce the SGPC's role as a central religious authority.

The Punjabi Suba Movement: A Political Milestone

A crucial aspect of the SGPC's involvement in Punjab politics was its support for the Punjabi Suba Movement. This movement, led primarily by the Akali Dal with significant backing from the SGPC, advocated for the creation of a Punjabi-speaking state. It was characterized by a series of protests, hunger strikes, and arrests, with over 57,000 Sikhs detained during the agitation. The successful culmination of this movement in 1966, with the establishment of the Punjabi-speaking state of Punjab, marked a significant victory for the SGPC and the Punjabi-speaking community in general and the Sikh community in particlar.

The Punjab Reorganisation Act of 1966

The passage of the Punjab Reorganisation Act on September 18, 1966, and the subsequent creation of the new State of Punjab on November 1, 1966, alongside Haryana and certain areas being transferred to Himachal Pradesh, were direct outcomes of the movement. This reorganisation was a pivotal moment in regional politics, altering the political, linguistic and cultural landscape of northern India.

SGPC's Role in Managing Sikh Affairs

Throughout this period, the SGPC not only engaged in political advocacy but also continued its primary role in managing Sikh gurdwaras and religious activities. This involvement ensured that Sikh religious traditions were maintained and that the gurdwaras operated as centres of faith and community gathering.

Summarising SGPC's Impact (1947-66)

The period from 1947 to 1966 was marked by significant political and social changes in Punjab, with the SGPC often at the forefront of these developments. The establishment of a Punjabi-speaking state was not just a political achievement but also a cultural affirmation for the Sikh community. As we further examine the historical trajectory of the SGPC, it's clear that its influence extended beyond religious management to shaping the socio-political fabric of Punjab. This legacy of active engagement and advocacy provides valuable lessons for ongoing governance and community leadership within the Sikh diaspora.

Evolution of the SGPC: Key Events from 1966 Onwards

1966: Reorganisation of Punjab

The division of Punjab into the states of Punjab, Haryana, and parts transferred to Himachal Pradesh in 1966 reshaped the jurisdiction and the administrative landscape of the SGPC. Despite these changes, the SGPC maintained control over the notified historical Sikh gurdwaras in Punjab, Chandigarh, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh, ensuring continuity in their governance.

1970s-1990s: Gurcharan Singh Tohra's Leadership

Gurcharan Singh Tohra's presidency, spanning over 27 years from 1972 to 2004 with some interruptions, marked a significant era in SGPC's history. His leadership was pivotal during a period of intense political activity and was crucial in guiding the SGPC through challenges and milestones.

1984: Operation Blue Star

The utterly condemnable and egregious storming of the Golden Temple complex by the Indian Army in June 1984, purportedly aimed at removing Sikh militants, left deep scars on the Sikh community. The operation resulted in severe damage to the Akal Takht and intensified Sikh sentiments and distrust towards the Indian government.

1984: Aftermath of Indira Gandhi's Assassination

The assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards in October 1984 triggered a horrific wave of anti-Sikh violence across India, notably in Delhi and Kanpur, leading to incalculable loss of life and property. This period underscored the vulnerability of Sikhs in the national socio-political landscape.

1984-1985: Reconstruction of Akal Takht

The SGPC's decision to undertake the reconstruction of the Akal Takht through "kar sewa" (volunteer service) after rejecting the government's rapid rebuilding efforts was a critical move. This not only helped restore the physical structure but also aimed to heal the community's sentiments and reclaim their autonomy over religious affairs, including the cardinal tenet of Miri-Piri.

1985: Rajiv-Longowal Accord

The Rajiv-Longowal Accord, signed between Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Akali Dal leader Sant Harchand Singh Longowal, was designed to address long-standing grievances and meet various demands of the Sikh community. Despite the tragic assassination of Sant Longowal just months after the accord's signing, this agreement had significant implications for Punjab’s populace, its political landscape, and the broader Sikh political agenda. It also influenced the role of the SGPC, marking a critical juncture in its involvement in Sikh political matters and shaping future dialogues and developments within the region.

Post-1985: SGPC's Ongoing Role

In the years following these tumultuous events, the SGPC has continued to be a central figure in Sikh religious and political spheres. It has navigated internal politics, interactions with the Indian government, and various community issues, maintaining its position as a key stakeholder in advocating for Sikh rights and managing religious affairs.

Representation and Challenges

With 170 elected members from different regions, the SGPC's structure and elections have sparked discussions about representation, particularly about voting rights and participation of various Sikh groups. These debates reflect the ongoing evolution of the SGPC as it adapts to the changing dynamics of the Sikh community.

In summary

The journey of the SGPC since 1966 highlights its critical role in shaping and responding to the Sikh community's challenges and aspirations. As we look towards the future, the SGPC's ability to adapt and address the needs of the Sikhs will be crucial in its ongoing mission to uphold Sikh religious governance and community welfare.

Development of the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee

Background and Initial Demand

The call for a separate gurdwara management committee in Haryana has been a significant issue among Sikh leaders in the state, distinct from the Amritsar-based Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC). This demand culminated in a legislative response from the Haryana Government.

Legislative Action

In 2014, the Haryana Government passed the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara (Management) Act, creating the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee (HSGMC). This move aimed to address local governance issues and represent the distinct needs of the Sikh community in Haryana.

Opposition and Legal Challenges

The establishment of the HSGMC was met with strong opposition from the SGPC and the Shiromani Akali Dal, leading to several legal challenges. These disputes underscored the contentious nature of religious and administrative autonomy in the region.

Judicial Intervention

The legal battles culminated in a Supreme Court ruling on September 20, 2022, which upheld the constitutional validity of the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara (Management) Act, 2014. A subsequent review petition filed against this decision was dismissed in February 2023, affirming the Act's legality.

Current Status and Ongoing Issues

Despite the legal clearance, the actual operationalization of the HSGMC has faced delays. As of July 2024, elections for the HSGMC have not been held. This has led to significant discontent among local Sikh leaders and community members, who have been advocating for the Haryana Government to conduct elections before the upcoming state assembly elections. Currently, a government-nominated body manages the HSGMC, but its tenure expired on May 31, 2024, leading to further calls for the establishment of an elected body.

Community Demands

The delay in holding elections has sparked further demands from Sikh groups in Haryana, who argue that the management of gurdwara affairs by a non-elected body is not in line with legal and community expectations. These groups are pressing for immediate elections to ensure that gurdwara management aligns with democratic principles and community representation.

Truncated Jurisdiction of SGPC, Sans Haryana

The establishment of the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee (HSGMC) marks a pivotal step towards catering to the specific religious and administrative needs of Sikhs in Haryana. However, this development is viewed by the SGPC and a broad cross-section of Sikhs in Punjab as a calculated move by anti-panthic forces to dilute the significance and influence of the SGPC and potentially divide the Sikh community along state lines within India. Despite these concerns, the transition has encountered numerous legal and operational challenges. The ongoing delays in conducting elections underscore the complexities of religious governance and underscore the urgent need for actions that align with both legal frameworks and community expectations. This situation continues to be a focal point for Sikh leaders and the wider community, highlighting the critical role of representative governance in managing religious affairs.

Advocacy for an All-India Sikh Gurdwara Act

Origins and Development of the Demand

The call for an All-India Sikh Gurdwara Act has been a central theme in Sikh community advocacy, dating back to the inception of the Sikh Gurdwara Act of 1925. This demand has evolved significantly over the decades, gaining momentum particularly from the late 1950s and further intensifying after the reorganisation of Punjab in 1966. The SGPC has consistently espoused its support for this cause, passing multiple resolutions to advocate for a unified legislative framework that would govern Gurdwara management across India. Notably, this demand was also a crucial element of the Anandpur Sahib Resolution adopted by the Shiromani Akali Dal in 1978, underscoring its long-standing significance within the community's broader political and religious agenda.

Legislative Efforts and Proposals

Multiple drafts and efforts have been made to bring the All-India Sikh Gurdwara Act to fruition:

In 1999, a draft was prepared by Chief Justice (retd) Harbans Singh.

In 2002, an amended draft was submitted by a screening sub-committee headed by Justice K.S. Tiwana.

Further momentum was seen in 2007 when the Badal government formed a committee to refine the All India Gurdwara Bill.

Despite these efforts, as of the latest updates, a pan-India legislation has not been enacted, leaving the management of Gurdwaras under various state-specific acts.

Management of Historic Sikh Gurdwaras Outside Punjab

Different regions manage their historic Sikh shrines through distinct legislative frameworks:

Delhi: Managed under the Delhi Sikh Gurdwaras Act of 1971.

Nanded (Hazur Sahib) and Patna Sahib: Governed by their respective acts established in the mid-20th century.

Both Takht Sri Patna Sahib in Bihar and Takht Sri Hazur Sahib in Maharashtra are under essentially under state control, with ongoing demands from organizations like the Global Sikh Council to return these Takhts to community management.

Recent Developments

In response to specific local needs, some state-level advancements have been made, such as the Punjab Cabinet's 2023 proposed amendment of the SGPC Act, 1925 to ensure free-to-air live telecast of Gurbani from Sri Harmandir Sahib. This, however, has still not received the assent of the Governor of Punjab and hence does not have the force of alw.

Gurdwara Management in Jammu and Kashmir

Legislative Framework

Jammu and Kashmir has its unique act, the Jammu and Kashmir Sikh Gurdwaras and Religious Endowments Act, 1973 which oversees the management and administration of Sikh Gurdwaras in the region. Interestingly the definition of a “sikh” in the J&K law is different from the one in the SGPC Act, 19252.

Recent Community Initiatives

In March 2024, the formation of the All Kashmir District Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee Coordination Committee marked a significant step towards addressing community-specific issues in Kashmir. This includes advocating for the status recognition of Sikh-inhabited areas, job packages for youth, political reservation, and the promotion of the Punjabi language in schools.

Historic Gurdwaras in Kashmir

Kashmir hosts several historic Gurdwaras like Chatti Patshahi and Gurdwara Guru Nanak Dev Ji, each with deep cultural and religious significance to the local Sikh community. The management of these shrines is distinct from the SGPC's jurisdiction, reflecting the unique regional context of Sikhism in Kashmir.

Challenges in the Pursuit of an All-India Sikh Gurdwara Act

The quest for an All-India Sikh Gurdwara Act remains a significant focus of Sikh community advocacy, aimed at centralizing the management of Gurdwaras across India under one legislative umbrella. Despite numerous legislative initiatives and persistent community advocacy, the fulfillment of this vision is still pending. This ongoing struggle is not only shaped by efforts and discussions but also significantly hindered by resistance from Sikhs living outside Punjab. These concerns stem from fears that an all-India enactment might disproportionately empower Sikhs from Punjab due to their numerical majority, potentially marginalizing the role and influence of Sikhs from other regions in managing their historical Gurdwaras. This complex dynamic continues to influence the discourse and direction of the proposed legislation, highlighting the need for a balanced approach that considers the diverse interests within the Sikh community.

Sehajdhari Sikhs and SGPC Elections: A Legal and Historical Overview

Definition of Sehajdhari Sikhs

The term "Sehajdhari Sikh" is defined in the Sikh Gurdwaras Act of 1925 as someone who adheres to key Sikh practices and beliefs but may not have taken the Khalsa baptism. Specifically, a Sehajdhari Sikh:

Performs ceremonies according to Sikh rites.

Abstains from tobacco and halal meat.

Is not considered "patit" or apostate.

Recites the Mul Mantra of Sri Guru Granth Sahib.

Believes in the ten Sikh Gurus and the Guru Granth Sahib.

Professes no other religion.

Understanding the Term "Sehajdhari Sikh"

It is essential to recognize that the term "Sehajdhari Sikh" represents a deeply engaged follower of Sikhism, possessing attributes and qualifications that extend beyond the basic definition of a "Sikh" as outlined in the SGPC Act of 1925. Contrary to being seen as an inchoate or incomplete Sikh, a Sehajdhari Sikh often embodies a profound connection to Sikh principles and practices, perhaps even more so than those simply categorized under the standard legislative definition. This nuanced understanding highlights the breadth of commitment within the Sikh community, acknowledging the diverse ways individuals relate to and practice their faith.

Historical Voting Rights

Historically, Sehajdhari Sikhs had the right to vote in SGPC elections, a practice that continued for several decades post-Indian independence. This inclusion reflected the inclusive nature of Sikhism, recognizing varied levels of religious practice within its community.

2003 Executive Notification

A significant shift occurred on October 8, 2003, when the Government of India issued an executive notification de facto amending key sections of the Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925. This amendment operated to effectively disenfranchise Sehajdhari Sikhs— stated to be over 70 lakhs— from voting in SGPC elections, marking a pivotal change in their democratic rights of participation.

2011 High Court Ruling

The 2003 executive notification was challenged legally, culminating in a critical 2011 ruling by the full- bench Punjab and Haryana High Court. The court quashed the Government of India notification on the grounds that such a significant legal right could not be revoked without full-fledged legislative action. This decision also essentially nullified the results of the SGPC elections held in September 2011, since these had been held to the exclusion of the Sehajdhari Sikhs.

2016 Parliamentary Amendment

In response to the High Court's decision, the Indian Parliament retrospectively enacted the Sikh Gurdwaras (Amendment) Bill, 2016, which was:

Passed by the Rajya Sabha on March 16, 2016.

Passed by the Lok Sabha on April 25, 2016.

Signed into law by the President in May 2016. This legislative change retrospectively barred Sehajdhari Sikhs from voting in SGPC elections starting from the date of the original executive notification in 2003.

Amendment Controversy Involving Sehajdhari Sikhs

This contentious amendment, which affected the rights of Sehajdhari Sikhs, was implemented under significant pressure from the Parkash Singh Badal-led Shiromani Akali Dal government in Punjab, facilitated by the Narendra Modi government. Arun Jaitley, the then Law Minister, played a crucial role in this process. The amendment was met with widespread criticism from the Sehajdhari Sikh community, who felt not only disenfranchised but also effectively ostracized from the broader Sikh community. This move highlighted the complex interplay of political influences and community dynamics within Sikh governance.

Current Status and Ongoing Legal Challenge

As a result of the 2016 amendment, Sehajdhari Sikhs currently do not have voting rights in SGPC elections. However, the issue remains legally contested. The Sehajdhari Sikh Party filed a civil writ petition (No. 11978 of 2017) challenging the amendment's constitutional validity. As of August 2024, the Punjab and Haryana High Court has issued notices to relevant parties, including the Union of India, State of Punjab, and SGPC, signaling that the legal proceedings are ongoing.

In Summary

The disenfranchisement of Sehajdhari Sikhs from SGPC elections remains a contentious issue with significant implications for Sikh community governance and religious representation. The ongoing legal battle underscores the complexities involved in balancing traditional religious practices with modern legal frameworks. As this situation continues to unfold, it represents a critical juncture in the intersection of religion, law, and politics within the Sikh community.

Current State of the SGPC: Elections, Leadership, and Challenges

Recent SGPC Elections and Leadership

The last SGPC election took place in 2011, and the General House elected since then has continued to operate, with annual elections to select the SGPC President. Advocate Sardar Harjinder Singh Dhami was elected for his third consecutive term in November 2023, indicating a continuation of leadership influenced by nominees associated with the Badal family, a prominent political force, if not in Punjab in general, then at least among the existing class of SGPC Members.

Challenges in Voter Registration for the SGPC

A significant challenge facing the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) is the marked decline in voter registration, with numbers plummeting from approximately 52 lakh in 2011 to about 27.87 lakh by July 2024. This sharp decrease is not attributable to natural demographic trends or migration, as such declines are not mirrored in the voter registrations recorded by the Election Commission of India for Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections. It's important to note that this reduction is not solely due to the exclusion of Sehajdhari Sikhs from voter enrollment—since they were also excluded in the 2011 elections due to the 2003 executive notification by the Government of India. This nearly 50% decrease, irrespective of the underlying reasons, raises serious concerns about community engagement and the representativeness of the electoral process within the Sikh community, indicating a deeper issue affecting participation and interest.

Gurdwara Election Commission

The appointment of a new Sikh Gurdwara Election Commission, headed by retired Chief Justice SS Saron, marks an attempt by the Government of India to address issues related to the management and fairness of SGPC elections.

Voter Eligibility and Legal Challenges

The definition and eligibility criteria for voters have been subjects of legal scrutiny and societal debate, particularly regarding Sehajdhari Sikhs—those who cut their hair or trim their beards, who are currently ineligible to vote. This exclusion, as stated before, is under legal review, with a pending case in the Punjab and Haryana High Court challenging the constitutionality of such restrictions.

Registration Extension and Low Turnout

Despite the extension of the voter registration deadline to September 16, 2024, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) has not witnessed an increase in claim applications for being registered as voters. This persistently low turnout is alarming and signals broader issues concerning community participation in SGPC governance. In response to these challenges, the Sikh Gurdwara Commission has made the requirement for a photograph of Sikh women on their voter registration applications optional rather than mandatory. This is in spite of the fact that the claims lodged by women Sikh Sikh voters far exceeds their male counterparts.

This decision has, however, sparked considerable debate, attracting criticism from various quarters. Critics question the necessity of this change, particularly when Sikh women routinely provide photographs for other official documents such as Election Commission of India voter cards, PAN cards, and passports. This controversy highlights ongoing tensions and discussions about identity, privacy, and administrative practices within the Sikh community's electoral processes.

Political Dynamics

The political landscape surrounding the SGPC elections is intricate and multifaceted. The Shiromani Akali Dal, which has traditionally been a dominant force in SGPC politics, is currently grappling with internal divisions, apart from the emergence of other 'panthic' forces in Punjab. Additionally, other political parties show a lack of enthusiasm for engaging in the SGPC electoral process. This disinterest may stem from the perceived diminishing influence of the SGPC or a reluctance to delve into the complexities and sensitivities of Sikh Gurdwara politics. This evolving political scenario presents significant challenges for the governance and future direction of the SGPC.

Youth Participation and Upcoming Elections

A significant concern within the Sikh community is the disenfranchisement of young Sikhs who have reached the age of 21 since the last SGPC election in 2011 but have not yet had the opportunity to vote due to the absence of subsequent elections. The uncertainty about when the next SGPC elections will be held, combined with pending panchayat elections in Punjab, further complicates the issue. This situation prompts a legitimate query: if individuals are eligible to vote in general elections at 18, why shouldn't the SGPC voting age be aligned with national electoral standards? This discrepancy highlights a crucial area for potential reform in the governance of Sikh electoral processes, emphasizing the need for updates to better reflect current democratic norms.

Very Briefly

The current state of the SGPC reflects a multitude of challenges, from legal battles over voter eligibility to political instability and a significant decline in voter engagement. These issues highlight the need for comprehensive reforms to ensure that the SGPC remains a relevant and effective institution for managing Sikh religious affairs and representing community interests. The upcoming decisions, both in the courts and at the ballot box, will be crucial in shaping the future of this pivotal religious body.

Future Pathways for the SGPC: Navigating Challenges and Embracing Opportunities

Current State of the SGPC

The Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) faces a multitude of challenges that have sparked widespread criticism and concern within the Sikh community. These challenges include:

Political Influence: There is a growing perception that the SGPC has become too entangled with the Shiromani Akali Dal, as a political party, potentially compromising its independence and focus on religious leadership.

Declining Voter Base: The significant drop in registered voters may reflect a decreasing relevance or disillusionment among the community, highlighting an urgent need for revitalization.

Conversion to Other Religions: This could also perhaps signal the conversion of the Sikhs, especially from amongst the SC community, to Christianity in numbers larger than normally estimated.

Limited Geographic Scope: While influential within Punjab and its neighbouring states, the SGPC's impact on the global Sikh diaspora is less pronounced, which could be expanded.

Exclusionary Practices: The disenfranchisement of specific groups within the community, like Sehajdhari Sikhs and younger Sikhs who trim their beards, has raised concerns about inclusivity.

Technological Stagnation: There is a notable gap in adopting modern technologies which could otherwise enhance translations, education, and global communication.

Social Issues: Issues such as caste divisions and the conversion of Sikhs to other religions indicate deeper social challenges that need to be addressed.

Suggested Reforms

To address these criticisms effectively and to ensure its continued relevance and effectiveness, the SGPC may consider implementing several strategic reforms:

Enhancing Independence: By distancing itself from direct political affiliations, the SGPC can better serve the religious and community-focused needs of Sikhs globally.

Expanding Global Outreach: Utilizing modern communication and translation technologies could help spread the teachings of Sikh Gurus more widely and deepen the global influence of Sikhism.

Inclusivity in Representation: Resolving eligibility issues through community dialogue rather than litigation could foster a more inclusive atmosphere and widen participation in SGPC elections.

Engagement with Youth: Lowering the voting age to 18 could align with broader democratic norms and energize younger community members to participate in SGPC governance.

Educational Initiatives: Focusing on educational upliftment, particularly among marginalized groups within the Sikh community, could help address social inequalities and strengthen community bonds.

Addressing Conversions: Developing comprehensive strategies to understand and address the reasons behind religious conversions is crucial for maintaining the cohesion and identity of the Sikh community.

Integrating Diverse Sects: Encouraging dialogue and cooperation among various Sikh sects could promote unity and collective action on broader issues affecting Sikhs.

Regular Elections: Timely and regular elections are essential for maintaining democratic legitimacy and ensuring that leadership remains responsive to the needs of the community.

Conclusion: Strategic Reforms for SGPC's Future Viability

For the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) to maintain its crucial role into the 21st century, it must not only embrace reform and modernization but also faithfully uphold the deep spiritual and cultural traditions of Sikhism. This task requires a comprehensive and coordinated effort involving multiple stakeholders: the Government of India, the Punjab Government, SGPC itself as a statutory body, political entities especially the Shiromani Akali Dal, and various Sikh organizations, NGOs, and charitable bodies. Additionally, it's vital to incorporate perspectives from the global Sikh diaspora, which can offer unique insights and support.

This process of transformation will demand openness to change, robust engagement with diverse community viewpoints, and a steadfast commitment to navigating contemporary challenges and seizing new opportunities. Through such collective and transformative efforts, the SGPC can rejuvenate its mission, extending its influence beyond the management of holy and historical Sikh Gurdwaras. By doing so, it can continue to act as a beacon of guidance and unity for Sikhs worldwide, fostering a vibrant community aligned with its rich heritage and the dynamic landscapes of the modern world.

“Sikh” means a person who professes the Sikh religion or, in the case of a deceased person, who professed the Sikh religion or was known to be a Sikh during his lifetime.

If any question arises as to whether any living person is or is not a Sikh, he shall be deemed respectively to be or not to be a Sikh according as he makes or refuses to make n such manner as the State Government may prescribe the following declaration: -

“I solemnly affirm that I am a Sikh, that I believe in the Guru Granth Sahib, that I believe in the Ten Gurus, and that I have no other religion.”

Definition in the J&K law: ‘Sikh’ means a Sikh who believes in ten Sikh Gurus and Guru Granth Sahib and keep Keshas

Good article. But you missed to mention that SGPC glorifies terrorists like Bhindrawala and has put up portraits of him and others in Sikh museum. SGPC has brought defamation to Sikhs by doing this. Also, why SGPC allowed hijack of Harmandir Sahab by terrorists. There are hundreds of issues with SGPC, the biggest one being that it is far from Gurus’ messages in SGGS.