Arvind Kejriwal Summoned by ED on 2/11: Answering FAQs regarding PMLA, 2002.

Summoning of Arvind Kejriwal by Enforcement Directorate: Understanding the Basic Legal framework of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002. 15 Frequently Asked Questions Answered.

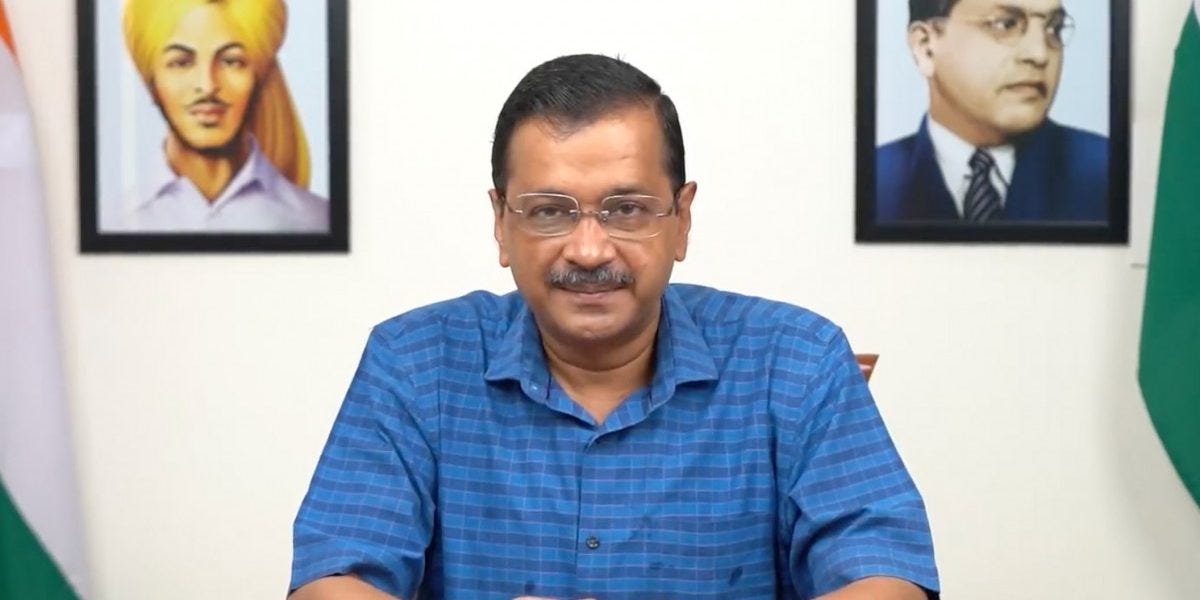

ED Summons Arvind Kejriwal

Arvind Kejriwal, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) leader and Delhi's Chief Minister, has been summoned by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) for questioning on November 2, 2023. This is in relation to alleged irregularities concerning the now-scrapped Delhi Excise Policy for 2021-22. This represents the second time a central probe agency has summoned the Delhi Chief Minister in this case. Previously, on April 16, 2023, Kejriwal underwent nine hours of questioning by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), during which he responded to 56 queries.

This latest development from the ED comes hot on the heels of the Supreme Court's dismissal of the bail applications filed by the former Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia, in connection with CBI and ED cases pertaining to the same policy.

Clarifying Key Questions on PMLA: Our Caveat and Disclaimer

The aim of this article is not to speculate on the questions that may be posed to Mr Kejriwal, nor to predict the possible outcomes of the ongoing legal proceedings. Rather, we endeavour to answer some frequently asked questions that often perplex readers and lay citizens—including those with legal training—for whom authoritative answers are scarce. As a proactive caveat and disclaimer, it's important to note that we are not legally trained; therefore, readers are strongly advised to seek qualified legal guidance for academic or practical purposes.

1. Who has the Authority to Summon a Person under PMLA?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) 2002 of India, the authority empowered to summon any person during the course of proceedings is primarily the Directorate of Enforcement, which operates under the Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance.

Specifically, Section 50 of the PMLA, 2002, gives the power to the authorities to summon persons to give evidence or produce records. The section explicitly empowers the Director, Deputy Director, Assistant Director, and other officers not below the rank of an Assistant Director to summon and examine any person believed to be acquainted with the facts and circumstances of the case.

On one side of the spectrum, the provision helps streamline the process of investigation by empowering specific authorities, thereby making it efficient. This also adds an element of accountability to the proceedings under PMLA.

2. Is the individual informed about their role as a witness, suspect, or accused when summoned under the PMLA?

In the context of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) 2002, Section 50, which deals with the power of authorities to summon persons, does not explicitly specify whether the person being summoned is called in the capacity of a witness, a suspect, or an accused. The section generally mentions that any person "believed to be acquainted with the facts and circumstances of the case" may be summoned.

On one side of the spectrum, not specifying the capacity in which a person is summoned can be advantageous from an investigative standpoint. It allows for a more flexible approach to questioning, which might lead to more open and unguarded responses, potentially aiding the investigation.

On the other side, critics argue that the lack of clarity about the capacity in which a person is being summoned may lead to undue stress or concern. It can also potentially affect the summoned person's decision on whether or how to seek legal counsel.

In summary, while the PMLA, 2002, empowers authorities to summon persons for investigation, it doesn't explicitly require the authorities to specify the capacity in which a person is summoned. This can be both an asset and a point of concern, depending on one's perspective. Ideally, the implementation of this power should aim to balance the needs of effective law enforcement with the rights and concerns of those who are summoned.

3. Are statements recorded before Enforcement Directorate officers under oath? Can an individual refuse to answer questions on the grounds of self-incrimination, citing Articles 20 and 21 of the Indian Constitution?

One perspective holds that Articles 20 and 21 enshrine constitutional rights safeguarding an individual from being coerced into providing self-incriminating evidence. Within this framework, it could be argued that a person summoned under PMLA retains the right to decline answering questions that may incriminate them.

Conversely, another viewpoint emphasises the urgency of combating financial crimes and the necessity for effective investigation into money laundering, PMLA's primary objective. Critics argue that allowing individuals to refuse to answer questions could substantially hinder investigations.

In summary, the PMLA is silent on whether a person is under oath during questioning. Concerning self-incrimination, while the Act itself does not specify, Articles 20 and 21 of the Indian Constitution may be invoked to decline answering self-incriminating queries. Nonetheless, this is a nuanced matter often subject to judicial interpretation; hence, anyone in such a situation should ideally consult legal counsel to navigate these complexities.

4. What happens if a person knowingly makes a false statement before ED officers? Can such a statement be used as direct evidence in a trial? Is it similar to statements recorded under Section 161 of the CrPC, which can be disowned later? Are these statements signed by the person making them?

The matter of providing false statements during an investigation under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002 is a serious issue and can have legal repercussions. Section 50 of PMLA explicitly states that if a person, without reasonable cause, fails to produce documents or provide a statement, he shall be punishable with imprisonment, fine, or both. However, the Act does not explicitly address the issue of knowingly providing false statements during questioning by Enforcement Directorate (ED) officers.

Regarding the evidentiary value of the statement, the statement recorded under Section 50 of PMLA is generally treated with greater evidentiary weight compared to a statement recorded under Section 161 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC). Unlike statements made under Section 161 CrPC, which can't be signed and are not admissible as substantive evidence in a court of law, statements recorded under PMLA's Section 50 are generally considered to have more substantial weight during trials. They are generally signed by the person making the statement, adding to their evidentiary value.

On one side, the strong evidentiary value attached to such statements aims to facilitate the effective prosecution of money laundering cases, which are complex and often involve international elements.

On the other side, there are concerns about the potential for misuse of this provision, and the lack of adequate safeguards against coerced or false statements could have significant ramifications for the accused.

In summary, knowingly providing a false statement during a PMLA investigation is a risky and punishable act. Statements recorded under Section 50 of the PMLA are typically given more weight in a trial than those recorded under Section 161 of the CrPC and are generally signed by the person making the statement. However, the scope and implications of these statements may ultimately be subject to judicial interpretation. Therefore, it's crucial for any person who finds themselves in such a situation to seek qualified legal advice.

5. When and how is an individual formally informed that their status has changed from a witness to an accused in an ED investigation under the PMLA, 2002?

In the framework of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, the transition of a person's status from a witness to an accused is not always explicitly stated in the law. However, there are several formal procedures and steps which indicate this change in status.

Typically, the clearest indicator would be the issuance of a charge sheet or complaint against the individual under Section 45 of the PMLA. Once the Enforcement Directorate (ED) files a charge sheet naming the person as an accused, it becomes official that the individual is no longer considered merely as a witness.

Another potential indicator could be the arrest of the individual. Under Section 19 of the PMLA, the authority (usually not below the rank of a Deputy Director) has the power to arrest a person, which is a strong indicator that the person is no longer viewed merely as a witness.

On one side of the spectrum, the rationale for not explicitly notifying a person about their change in status could be to prevent the obstruction of ongoing investigations or the tampering of evidence. This approach may also discourage suspects from fleeing or taking other actions that could impede the investigation.

On the other side, critics argue that this lack of transparency can be problematic from a human rights perspective. It can lead to stress and anxiety for the individual involved, and possibly even affect their legal strategy.

In summary, while the PMLA, 2002 doesn’t lay down explicit procedures for notifying a person about their change in status from a witness to an accused, the filing of a charge sheet or an arrest would usually serve as such indicators. The law seeks to balance the complexities of money laundering investigations against the individual's rights, but the absence of explicit notification has both practical and ethical implications that are often subject to debate. Legal counsel is strongly recommended in such complex matters.

6. Does the Enforcement Directorate require a warrant to arrest an individual or search premises under the PMLA, 2002?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) 2002, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) has certain powers related to arrest and search, which are primarily covered under Sections 17, 18, and 19 of the Act.

Section 19, which deals with the power to arrest, states that if an authority (usually not below the rank of a Deputy Director) has reason to believe based on the material in his possession that an arrest is necessary, he may arrest the individual. The section does not explicitly require a warrant for the arrest.

Section 17 of the PMLA discusses the power to search premises. Again, an officer authorised in this regard can enter, search, seize, and arrest without requiring a warrant if he has reason to believe that any record or property related to money laundering is kept in any place.

One view argues that these provisions are designed to provide the ED with the flexibility and agility required to effectively combat money laundering, which often involves rapidly evolving situations and cross-border elements.

However, another perspective is that such sweeping powers could potentially be open to abuse. The absence of the need for a warrant could bypass the judicial scrutiny that acts as a safeguard against arbitrary arrests or searches, potentially leading to infringements on individual rights and liberties.

In summary, under the PMLA, 2002, the ED generally does not require a warrant to make an arrest or to search premises. While this grants the agency considerable latitude and effectiveness in its operations, it also brings up important questions about checks and balances, and the safeguarding of individual rights. Therefore, if someone finds themselves subject to such actions, seeking immediate legal counsel is advisable.

7. Are Enforcement Directorate officers considered police officers? Do confessions made before them hold any evidentiary value in court?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, officers of the Enforcement Directorate (ED) are not classified as police officers. They operate under the aegis of the Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance, and have specific powers granted to them for the enforcement of the PMLA.

The question of whether a confession made before an ED officer is admissible as evidence is subject to legal interpretation and has been a matter of judicial scrutiny. Since ED officers are not classified as police officers, confessions made to them do not fall under the purview of Section 25 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, which states that confessions made to police officers are not admissible in court.

On one hand, the argument is that because ED officers are not police officers, confessions made to them should be admissible in court. This would enable more effective prosecution in cases of complex financial crimes like money laundering.

On the other hand, critics argue that the coercive environment of an interrogation, whether conducted by the police or other agencies like the ED, could lead to false or involuntary confessions. Therefore, such confessions should be treated cautiously and perhaps not be given the same evidentiary weight as other forms of evidence.

In summary, while ED officers are not classified as police officers, the evidentiary value of a confession made before them is a matter of legal interpretation. The issue has both supporters and detractors, each arguing from the standpoint of either more effective law enforcement or the safeguarding of individual rights. Given these complexities, if one finds oneself in such a situation, seeking qualified legal advice is imperative.

8. What is an Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR) and how does it differ from a First Information Report (FIR) filed by the police in relation to a cognizable offence?

An Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR) is a document prepared by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) when initiating an investigation under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002. The ECIR serves as the first formal step in the investigative process for suspected money laundering activities and is equivalent to a First Information Report (FIR) filed by the police for other criminal offences.

However, there are significant differences between an ECIR and a police FIR:

Jurisdiction: FIRs pertain to a wide range of criminal offences under the purview of various laws and are filed by police officers. ECIRs are specific to cases of suspected money laundering and are filed by the ED.

Nature of Offences: FIRs can relate to both cognizable and non-cognizable offences, whereas ECIRs are related specifically to money laundering, which is a cognizable and non-bailable offence under the PMLA.

Trigger Point: An FIR is usually the first step in a criminal investigation and is based on either a complaint or information received by the police. An ECIR is often based on an existing FIR or charge sheet filed by another investigating agency. The ECIR itself might be the result of a Scheduled Offence that warrants the ED's involvement.

Authority: FIRs are filed by a police officer at a police station. ECIRs are filed by officers of the ED, who are not classified as police officers.

Admissibility: In terms of legal proceedings, FIRs and ECIRs serve different purposes. An FIR is intended to set the criminal law system in motion and is considered a public document that can be used in court to prove the facts contained in it. An ECIR serves a similar function but within the narrower confines of money laundering investigations.

Procedure: The procedures for filing and following up on FIRs are governed by the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), while the procedures for ECIRs are governed by the PMLA.

Public Access: Generally, FIRs are more accessible to the public, whereas ECIRs are confidential and shared only with the concerned authorities and individuals.

On one side, the specialised nature of ECIRs enables the ED to focus on complex money laundering cases, which require different expertise and resources compared to conventional crimes. On the other side, critics argue that this specialised system might lack the checks and balances inherent in the broader criminal justice system, potentially leading to misuse or abuse of power.

In summary, while both ECIRs and FIRs serve as initial steps in the investigation of offences, they are different in terms of jurisdiction, nature of offences, the authorities involved, and the legal frameworks governing them.

9. What is the concept of a predicate offence and a scheduled offence in PMLA?

The Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, in India, employs the concepts of "Predicate Offence" and "Scheduled Offence" to set the framework for anti-money laundering measures.

(i) Predicate Offence

The term "Predicate Offence" refers to the initial criminal act that generates proceeds which are subsequently laundered. Money laundering is essentially the process of making 'dirty money' appear legitimate, and for there to be money laundering, there must first be a 'dirty money' source, i.e., a Predicate Offence. These can include various types of crimes such as fraud, corruption, drug trafficking, and more.

(ii) Scheduled Offence

The concept of "Scheduled Offence" is specific to the PMLA and is defined in its Schedule, which lists various offences under the Indian Penal Code and other legislations. When an individual is suspected or found guilty of a Scheduled Offence, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) has the authority to attach and confiscate proceeds of crime generated from that offence under the PMLA.

The primary difference between a Predicate Offence and a Scheduled Offence lies in their scope:

Scope: A Predicate Offence is a broader concept and can include any criminal activity that produces illicit funds. A Scheduled Offence is specific to the list provided in the Schedule of the PMLA.

Jurisdiction: Predicate Offences are not limited to any particular jurisdiction and can include offences committed outside India, as long as the laundered money is brought into India. Scheduled Offences are specific to laws in India as listed in the PMLA Schedule.

Legal Framework: Predicate Offences could fall under various legal frameworks, both national and international. Scheduled Offences are strictly governed by the PMLA.

Enforcement: Scheduled Offences trigger the enforcement mechanisms under the PMLA, which include investigation by the ED, attachment of property, and prosecution.

From one viewpoint, these specific definitions allow for targeted action and specialised prosecution strategies. However, critics argue that the list of Scheduled Offences may not be comprehensive enough to cover all forms of Predicate Offences, thereby leaving loopholes in the anti-money laundering framework.

In summary, while the concept of a Predicate Offence serves to identify the origin of illicit funds in the broader context of anti-money laundering measures, a Scheduled Offence in the context of PMLA is a specific criminal offence that triggers the Act's enforcement mechanisms.

10. What are the scheduled offences under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002? Can you enumerate them?

The Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, in India, provides a comprehensive list of Scheduled Offences in its schedule, which can be modified from time to time by the Government, by notification in the Official Gazette. These offences are the predicate crimes that form the basis for invoking PMLA for money laundering activities. The schedule to the PMLA is divided into three parts: Part A, Part B, and Part C.

Please note that the following is a summary and not an exhaustive list. New offences may be added, and existing ones might be modified by legislative amendments.

Part A

This part includes offences under various Acts, such as:

Indian Penal Code, 1860 - Offences like waging war against the government, counterfeiting, murder, theft, extortion, cheating, etc.

Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985

Explosive Substances Act, 1908

Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967

Arms Act, 1959

Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972

Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956

Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988

Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, 1992

Customs Act, 1962

Competition Act, 2002

Companies Act, 2013/1956

Part B

This part deals with offences that attract imprisonment for more than three years under various laws but excludes offences under Part A.

Part C

This part includes offences at the international level, such as offences connected with the activities of terrorist groups or offences committed against a State and are recognised as such under international treaties, agreements, or conventions.

It's advisable to refer to the latest version of the PMLA Schedule for the most accurate and up-to-date list of Scheduled Offences, as legislative amendments could modify this list.

On the one hand, the inclusion of a wide range of offences under the PMLA Schedule allows for comprehensive action against money laundering that could stem from diverse criminal activities. On the other hand, critics argue that the long list could potentially be used as a catch-all mechanism, leading to possible misuse.

Please consult legal authorities or professionals for the most current and specific information.

11. Can an individual who has not been made an accused by other investigating agencies like the police or CBI be made an accused in a complaint case by the Enforcement Directorate?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) has the authority to initiate investigations into money laundering offences independently. It can register an Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR) based on information received from various sources, including other investigating agencies such as the police or the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI).

While it is common for the ED to take up cases based on FIRs or charge-sheets filed by other agencies (for the predicate or Scheduled Offences), it is not bound by the list of accused provided in those reports. Therefore, theoretically, the ED can name a person as an accused in its complaint case (commonly referred to as a prosecution complaint under the PMLA), even if that individual has not been named as an accused by other investigating agencies like the police or CBI.

There are, however, a few factors to consider:

Evidence: The ED would need to have sufficient evidence to show that the individual was involved in money laundering related to the predicate or Scheduled Offence under investigation.

Legal Scrutiny: Any such decision would be subject to legal scrutiny and the accused would have the right to challenge the ED's action in court.

Procedural Fairness: Given the gravity of money laundering charges, the due process of law must be meticulously followed to ensure fairness and justice.

On one hand, this autonomy allows the ED to conduct a thorough investigation and include anyone found to be involved in money laundering, even if they haven't been named by other agencies. This could be particularly beneficial in complex cases involving financial crimes, where the money laundering aspect may not be immediately apparent to agencies investigating the predicate offence.

On the other hand, critics argue that this level of autonomy could lead to potential misuse or abuse of power, particularly in politically sensitive cases.

In summary, while it is legally possible for the ED to name someone as an accused even if other agencies have not, such action must be backed by sufficient evidence and is subject to judicial scrutiny. Therefore, if someone finds themselves in such a situation, seeking qualified legal advice is essential.

12. Does simply possessing unaccounted cash or illicit funds amount to money laundering under the PMLA, 2002? Or is an additional substantive step required?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, mere possession of unaccounted cash or illicit funds does not automatically amount to money laundering. According to Section 3 of the PMLA, an act constitutes money laundering if it involves the acquisition, ownership, possession or use of proceeds of crime, and projecting or claiming it as untainted property.

The key elements for an offence to be classified as money laundering under PMLA are:

Proceeds of Crime: The money in question must be derived from a criminal activity constituting a Scheduled Offence under the Act.

Intent: There must be an intention to project such "proceeds of crime" as untainted money. This includes activities like conversion, transfer, and concealment of the origins of that money.

Knowing Involvement: The person must knowingly indulge in one or more of these activities.

Hence, some substantive steps other than mere possession are generally required for an act to qualify as money laundering. These could include:

Transferring the money through multiple bank accounts to obscure its origin

Investing the money in assets that appear legitimate

Using the money for legal business activities but mixing it with legally acquired funds to camouflage its source

Any other activity that serves to "launder" the illegal origins of the money

On one side, critics argue that the requirement for additional steps beyond mere possession ensures that innocent individuals who unknowingly come into possession of illicit funds are not immediately charged with a serious offence like money laundering. On the other side, proponents of stronger anti-money laundering measures may argue that this requirement makes it more challenging to prosecute cases, especially when the "laundering" activities are sophisticated and designed to evade detection.

In summary, while mere possession of unaccounted cash or illicit funds might raise red flags and lead to investigation, it does not automatically qualify as money laundering under PMLA. Additional elements like intent and action to project the funds as legitimate are generally needed for a charge of money laundering. Qualified legal advice should be sought in any situation where there is a question of potential involvement in money laundering.

13. If a person is discharged by a judicial court in a case led by the police or CBI, does the Enforcement Directorate's case against him automatically collapse?

The Enforcement Directorate (ED) operates under the framework of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, which is a separate legislation distinct from the Indian Penal Code or other statutes under which the police or the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) may file their cases. The ED investigates the offence of money laundering, which may be linked to a predicate or scheduled offence that is being investigated by another agency, but it's still a distinct offence.

Therefore, even if a person is discharged by a judicial court in a police or CBI case, it does not automatically mean that the ED's case against that person will collapse. A few important considerations are:

Independent Investigation: The ED conducts its own independent investigation into money laundering, which may involve facts and circumstances that are not covered by the original police or CBI case.

Different Charges: Money laundering is a separate charge with different elements to prove, so a person could be found not guilty of the original offence but still guilty of money laundering.

Judicial Scrutiny: While a discharge in the predicate offence could be considered as a mitigating factor, it is ultimately up to the judiciary to decide whether the ED's case holds merit.

Double Jeopardy: Article 20(2) of the Indian Constitution protects individuals from being prosecuted and punished for the same offence more than once. However, since money laundering and the predicate offence are considered different offences, this provision usually does not apply.

On one hand, the independence of ED investigations serves to ensure that money laundering, which often has more extensive and varied ramifications than the predicate offence, is adequately addressed. On the other hand, critics argue that this independence can lead to situations where individuals face prolonged legal battles even after being discharged from the original charges, which might be considered unfair.

In summary, while discharge from the original case could influence the ED's case and might be a point argued by the defence, it does not automatically result in the collapse of the ED's case. In such scenarios, it would be prudent for the person concerned to consult with legal professionals experienced in PMLA cases.

14. Can Enforcement Directorate officers arrest an individual without a warrant during their inquiry or investigation? If so, which ranks of officers have the authority to do so?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, Section 19 allows officers authorised by the Central Government to arrest a person, without a warrant, if they have reason to believe the person has been guilty of any offence punishable under this Act. Generally, these officers are of the rank of Deputy Director or above.

It's crucial to note that arrest under the PMLA is a serious action and generally occurs only when the officer has sufficient grounds to believe that the person in question is involved in money laundering. Following the arrest, due process as laid out in the Act and other related Indian laws is followed.

15. Does an ED Officer need to disclose the reasons or grounds for arrest, in writing, while arresting any person?

under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, Section 19(1) specifies that the person arrested "shall be informed of the grounds for his arrest." It is generally considered good practice for the arresting officer to provide these grounds in writing to ensure clarity and legal compliance, although the Act does not explicitly state that the grounds must be provided in written form.

The arresting officer is also required to produce the arrested individual before a judicial magistrate within 24 hours of the arrest, excluding the time necessary for the journey. During this production before the magistrate, the grounds for arrest are also expected to be clearly laid out.

Therefore, while the PMLA does not explicitly state that the grounds for arrest must be in writing, it does mandate that the arrested person be informed of the grounds, which usually includes providing them in a written format to avoid any ambiguity or legal complications.

Navigating the Complex Landscape of PMLA: A Cautionary Conclusion

The range of questions concerning the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) is extensive, especially when it comes to matters like the grant of bail, a topic we've explored in a separate recent article1. Additionally, the question of property attachment during the investigation, enquiry, or trial introduces a plethora of complexities. Given these intricacies, it is beyond the scope of this single article to provide comprehensive answers to all potential queries.

It's worth noting a general caveat: the provisions of the PMLA, 2002, are particularly stringent. Should you find yourself subject to these laws, we strongly recommend seeking the best possible legal aid promptly. The insights offered in this article reflect our best understanding and should not be viewed as irrefutable truths.

The primary objective of this article has been to educate the general reader about the basic tenets of the PMLA. This act has been in the spotlight recently due to the vigorous actions taken by the Enforcement Directorate against politically exposed figures and business leaders. We hope this serves to enhance general awareness and fosters a more nuanced understanding of unfolding events in the news.

Breaking News: Manish Sisodia's Bail Plea Dismissed by Supreme Court—can apply afresh in 3 months.

Major Setback for Sisodia In a significant blow to former Delhi Deputy Chief Minister, Manish Sisodia, a Supreme Court Bench comprising Justice Sanjiv Khanna and Justice SVN Bhatti today (barely minutes ago) dismissed his bail applications. However, the Court directed that the trial should conclude within a timeframe of 6 to 8 months. Should the trial f…

Stay Updated: Subscribe for Free

If you've come across this article through a forwarded email, consider subscribing directly. It's complimentary, and our freshly published articles will be quietly delivered straight to your email inbox.

Neither qualified nor knowledgeable on the subject but I do have a question.

It appears the process from identifying of wrong doing to determination is conducted by IRS ( Department of revenue /Finance) , is it true that it is controlled by the or could receive direction from ruling political or government Ministers ? Or it is as independent as election commision. IRS here didn’t hesitate catching US sitting VP Spiro T Agnew.

PMLA well explained and well narrated 👍