Women Reservation Bill: Thank you Modi ji but........

Women Reservation Bill: A Paradigm Shift in Indian Politics but pitfalls need to be avoided.

Introduction

The Women's Reservation Bill was cleared by the Union Council of Ministers, meeting under the chairmanship of PM Narendra Modi, on the evening of Monday, 18 September. This development has injected new vigour into the ongoing five-day Special Session of Parliament. Although all political parties agree in principle on the question of women's reservation, historical differences have often arisen when it comes to actual implementation. This has led to the proposals either being shelved or put on the back-burner.

Historical Background: A Peep into the Past

After the 72nd and 73rd Constitutional Amendments were enacted in 1992, notably under a minority government led by Narasimha Rao, women's reservation in Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) and Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) became a nationwide reality. This system has been in operation for nearly three decades. In it, women's reservation applies not just to the basic seats but, by rotation, also to higher offices such as Sarpanch of the Gram Panchayat, Chairpersons of Panchayat Samitis (Block Committees) and Zila Parishads, as well as Presidents of Municipal Councils and Mayors of Municipal Corporations.

Previous Attempts and Current Status

Earlier efforts to introduce and advance similar constitutional amendment Bills occurred on multiple occasions. However, because these Bills were presented in the Lok Sabha, they lapsed in 1996, 1998, and 1999, following the dissolution of the Lok Sabha. In contrast, the current 108th Constitutional Amendment Bill, introduced in the Rajya Sabha in 2008 and subsequently passed by it in 2010, remains technically and legally viable, as the Upper House is considered a permanent body.

What next? Need for a political consensus

While no official confirmation is immediately available, it remains a matter of speculation whether the new Bill introduces any fundamental changes to the 2008 Bill, which has languished in the Indian Parliamentary system for over a decade. Needless to say, political consensus across all parties is essential, given that such a constitutional amendment bill must be passed by a two-thirds majority of the members present and voting in each of the two Houses of Parliament. Therefore, even if a minor amendment to the original draft bill is made, the issue will also need to return to the Rajya Sabha for approval by a two-thirds majority. This is in addition to the constitutional requirement of ratification by at least half of the state legislatures.

Why no details? Matter of Parliamentary Propriety

Even in the absence of the finer details of the proposal approved by the Union Cabinet being made public, the main opposition party, the Congress, was quick to not only support the proposal but also keen to assert that the original idea came from then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. They pointed out that the reservations in PRIs and ULBs were implemented in 1992 during the prime ministership of the Congress-led government of Narasimha Rao. A Minister who attended last evening's Cabinet meeting confirmed that, given that Parliament is in session, parliamentary propriety dictates that details should only be divulged to the general public after the Bill is tabled in the Lok Sabha, either today (i.e., 19th September) or on a subsequent date.

Salient Features and Beyond

The key features of the previous proposal, already well-documented in the public domain, will be succinctly summarised by us. However, the crux and a unique aspect of our brief discussion here is to offer an analysis of the politics surrounding the implementation of the reservation scheme. This extends beyond the newspaper headlines and delves into the intricacies that will arise once the constitutional amendments are officially notified and become an integral part of the Constitution of India.

Further reservation for SC Women?

Firstly, as the proposed amendments are slated to have an initial duration of 15 years, it's evident that the seats reserved for women will rotate over three general elections, thereby covering all constituencies over this period. This is distinct from the reservation for Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST), which, once allocated to a specific constituency, generally continues indefinitely or at least until the next delimitation exercise. As a result, the advantage of women's reservation will shift to a different constituency in each subsequent general election.

No Permanent Male, or Even Female, Preserves

This carries two further implications. First and foremost, a female candidate who wins from a specific seat due to reservation will need to contest from the same constituency as a general candidate in the next election if she wishes to run for the Lok Sabha or Vidhan Sabha from the same seat.

Secondly, and perhaps more significantly, there will be no enduring male strongholds; every sitting male MP or MLA will see his seat falling under the purview of women's reservation over the next two or three election cycles. Consequently, the tradition of nurturing a particular constituency may become diluted, as incumbents and prospective candidates will likely focus on the interests of not only their current constituencies but also their future ones.

My Experience from the Mid-1990s in Amritsar

At the onset of my career as an IAS officer in Punjab, I was assigned to the tumultuous district of Amritsar, which at that time also encompassed the current Tarn Taran district. I served there from 1990 to 1996, spending four years as the Deputy Commissioner/District Magistrate after an initial two-year tenure as the second-in-command. This period afforded me valuable, hands-on experience in conducting elections for Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) and Urban Local Bodies (ULBs), which had been in abeyance for several decades. Crucially, after the passage of the 72nd and 73rd Constitutional Amendments, we also grappled with the sensitive issue of implementing reservations for women in these electoral bodies.

Transparent and Rational Criteria Crucial for Success

Our central argument focuses not merely on the headline that one-third of the seats will be reserved for women, but more significantly on the underlying criteria or algorithms to be employed for selecting specific constituencies for women's reservation. Numerous nuances need to be proactively addressed, as the sequence in which constituencies are chosen for reservation could become a fertile ground for grievances, complaints, and even allegations. These could emanate not only from individual candidates but also from political parties, making transparency and rationality in selection criteria paramount for the success of this initiative.

Clarification Required— Now, Not Later

Is the selection and notification of constituencies reserved for women to be undertaken by the Central Government or the Election Commission of India? What will be the procedure for state Vidhan Sabhas? Will a formal criteria or algorithm be followed? Could it be a draw of lots, or will constituencies be chosen alphabetically—if so, in English or the local language? Alternatively, will the selection be serial number-wise, using the constituency numbers historically allotted in the electoral system? These questions necessitate immediate clarification to mitigate future controversies and ambiguities.

Clarity Available, Except in the Event of Fresh Delimitation

With the forthcoming delimitation of Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha constituencies set for 2026, well within the 15-year horizon of the proposed amendments, there is a need to clarify how this matter will be addressed. Thankfully, the Bill has dispelled uncertainties over additional reservations for SC and ST candidates within the seats reserved for women. As it stands, rather than introducing a new layer of reservations for these groups, the currently reserved seats for SC and ST candidates will rotate in favour of women. This means that while the SC/ST seats will remain fixed, a quota for women will be applied to them by rotation.

Voice of the Critics— Our Experience

Critics of the Women's Reservation Bill often argue that reserved seats may simply be filled by the wives, widows, daughters, and daughters-in-law of existing political leaders. However, drawing from my experience in Amritsar, even illiterate SC women candidates—who filed their nominations for posts such as Chairperson or Vice Chairperson of the Zila Parishad using thumb impressions—quickly acclimated to their roles and proved to be formidable competitors for their male counterparts.

Avoid the pitfalls

While we wholeheartedly welcome this courageous initiative by the Narendra Modi Government, and hope that minor political disagreements do not hinder its progress, it's essential that the post-reservation mechanism be as objective and transparent as possible from the outset. Failing to do so could result in significant delays and excessive litigation. Moreover, it could give rise to claims from male political figures, who might allege that the reservation of their constituency seat for women was politically motivated.

Let’s Move Fast

If the Indian Parliamentary system acts swiftly, which is entirely feasible given the apparent consensus across the political spectrum on this issue, we could witness a transformative change in the gender profile of the next Lok Sabha by 2024. While the group photographs will undoubtedly be more colourful, featuring female Members in their finest traditional attire, what is of paramount importance is the potential for issues affecting women—such as rape, sexual harassment, dowry deaths, and female infanticide—to gain greater visibility and higher priority on the national parliamentary agenda.

Summing Up and the Way Forward

In conclusion, kudos to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party for leading the charge on this transformative initiative, as well as to all political parties that have lent their support to this groundbreaking proposal. It is our fervent hope that the measure will be carried through to its logical conclusion as swiftly as possible, ideally addressing the questions surrounding rational criteria that we have previously flagged.

Thank you, Modi ji.

UPDATE

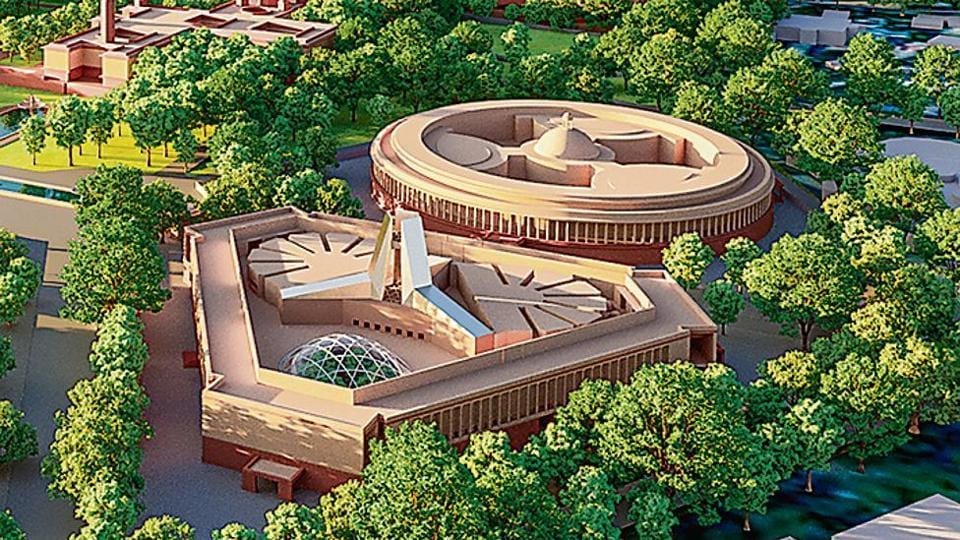

We turn our attention to the 128th Constitutional Amendment Bill that was tabled in the Lok Sabha this Tuesday (i.e.19th September, 2023), a significant development that warrants immediate analysis.

Firstly, it's worth noting the change in the Bill's numbering. With the previous Bill being the 108th, introduced in the Rajya Sabha in 2008 and passed in 2010, the new numbering—128th—indicates that alterations have been made, however minor they may be.

Secondly, the Bill is set to come into effective play only after the completion of the delimitation exercise, due in 2026, meaning it will not be applicable for the forthcoming Lok Sabha elections in April-May 2024. Instead, it will impact the electoral landscape in 2029.

Thirdly, there is a strong likelihood that the Bill will be passed during the tenure of the current Lok Sabha. If it garners approval from both Houses of Parliament with a two-thirds majority of the members present and voting, it will then be forwarded for ratification by at least half of the State Vidhan Sabhas.

In summary, we are 'hastening slowly,' as the adage goes. Nonetheless, moving cautiously but progressively is far better than remaining at a standstill, as has been the case for many years.

The wheels of change are in motion, even if they are turning more slowly than some might hope. Yet, it's crucial to remember that enduring reform is often the result of measured, deliberate action.

Great Achievement of the Modi Government!

Women's Reservation Bill to be tabled in Lok Sabha today at 3 PM.

Stay tuned.