When Lawmakers become Lawbreakers: Disqualification of MPs/MLAs upon Criminal Conviction

From Criminal Charges to Political Disqualification: Understanding the Legal Framework for MPs/MLAs.

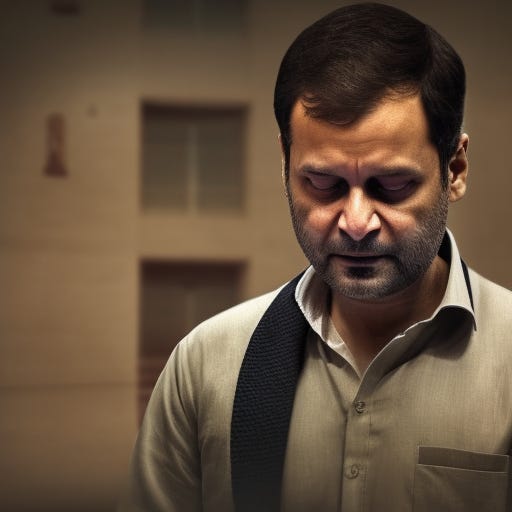

Rahul Gandhi’s conviction and 2-year sentence in a criminal defamation case bring into focus the question of disqualification.

Rahul Gandhi’s conviction in a criminal defamation

The Congress leader and MP Mr Rahul Gandhi was on Thursday (23.03.2023) convicted by a Gujarat court in a defamation and handed over a stiff 2-year sentence, the maximum permissible under the law for this offence. Although the court stayed the sentence and granted him interim bail to file an appeal, there has been tremendous interest in political as well as in media and academic-legal circles regarding whether such an event would lead to his immediate and automatic disqualification from the Membership of the Lower House. Also, whether he stands disqualified from contesting elections in future and, if so, for what period of time.

Constitutional provisions

The constitutional provisions relevant to the disqualification of a Member of Parliament in India in the event of their being convicted for a criminal offence are quite unambiguous. Article 102(1)(e) of the Constitution of India provides that a person shall be disqualified for being chosen as, or for being, a Member of Parliament if they are convicted of an offence and sentenced to imprisonment for two or more years, unless a stay of the conviction AND sentence both has been granted by a court. There are similar and analogous provisions under Article 191(1)(e) of the Constitution for MLAs and MLCs of the state legislature.

Representation of People Act, 1951

These constitutional provisions reinforce the disqualification criteria laid down in the Representation of the People Act, 1951, and provide the legal basis for disqualifying a Member of Parliament or a state legislature in India on the ground of conviction for a criminal offence. Section 8 of the Act lays down various grounds for disqualification of a person for being chosen as, or for being, a Member of Parliament. One of the grounds for disqualification is a conviction for an offence AND the sentence of imprisonment for two years or more.

However, there are some exceptions to this provision. A person who has been convicted of any offence and sentenced to imprisonment for less than two years is not disqualified if:

the conviction has been stayed by a higher court; or

an appeal or application for revision is pending before a higher court against the conviction and sentence.

In addition, a person who has been convicted of any offence and sentenced to imprisonment for two years or more is not disqualified if:

an appeal or application for revision is pending before a higher court against the conviction and sentence; and

the conviction AND sentence have been stayed by the court.

The words “or” and “and” as highlighted above make an important distinction. For a sentence of two years or more, in order to escape the disqualification that would ordinarily follow, both the sentence and the conviction ought to have been stayed by a superior court, in appeal or in revision. It is also important to note that a person who has been disqualified from being a Member of Parliament or State Legislature cannot contest elections for a period of six years from the date of disqualification.

Who passes the formal order of disqualification?

The formal order of disqualification of a Member of Parliament in India, following their conviction for a criminal offence, is passed by the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha (for members of Rajya Sabha) or the Speaker of the Lok Sabha (for members of Lok Sabha). After a member of Parliament is convicted of an offence and sentenced to imprisonment for two or more years, the Secretary-General of the Lok Sabha or the Rajya Sabha receives a copy of the judgment and conviction order from the concerned court. The Secretary-General then examines the case and submits the case to the Speaker or Chairman of the respective House for further action.

The Speaker or Chairman then examines the case and, if satisfied that the member has incurred disqualification, issues a formal order of disqualification. The order is then communicated to the Election Commission of India and published in the Gazette of India and the seat is declared vacant, paving way for a by-election.

Opportunity of personal hearing

According to the principles of natural justice, a person who is facing the possibility of being disqualified from being a Member of Parliament has the right to be heard and defend themselves. Therefore, before passing a formal order of disqualification, the Speaker or Chairman of the House concerned usually gives the member an opportunity to explain their position and present their case. The Member is at liberty to submit a written representation to the Speaker or Chairman explaining why they should not be disqualified. In some cases, the Speaker or Chairman may also conduct an oral hearing where the member can present their case in person. After considering the Member’s representation and other relevant facts, the Speaker or Chairman will then decide whether to pass an order of disqualification or not.

It is underscored that while the Member has the right to be heard and defend themselves, the disqualification criteria laid down in the Representation of the People Act, 1951, and the Constitution of India are strict and leave little room for discretion on the part of the Speaker or Chairman in cases where the conviction and sentence both have not been stayed by an appellate court.

Navjot Singh Sidhu case

Navjot Singh Sidhu, a former Indian cricketer and politician, was accused of causing the death of a man in a road rage incident in Patiala, Punjab in December 1988. Here is a timeline of the case:

December 27, 1988: Navjot Singh Sidhu and his friend allegedly got into an argument with Gurnam Singh and two others over a parking spot in Patiala. The argument turned physical, and Sidhu allegedly punched Gurnam Singh, who fell to the ground and later died of his injuries.

January 2, 1989: A case was registered against Sidhu and his friend under various sections of the Indian Penal Code, including Section 302 (murder) and Section 34 (common intention).

September 22, 1999: A trial court acquitted Sidhu and his friend of all charges, citing lack of evidence.

December 1, 2006: The Punjab and Haryana High Court reversed the trial court’s decision and convicted Sidhu of culpable homicide not amounting to murder, under Section 304 Part II of the Indian Penal Code. He was sentenced to three years in prison.

December 1, 2006: The very same day, Sidhu, the sitting BJP MP from Amritsar, tendered his resignation as Member of Lok Sabha, “without resorting to technical arguments.”

January 15, 2007: Supreme Court stays the sentence as well as the conviction awarded by the Punjab and Haryana High Court, paving the way for his contesting the consequential by-election.

February 27, 2007 Navjot Singh Sidhu (BJP) won the by-election to the Amritsar Lok Sabha seat by a huge margin, defeating his nearest rival of the Congress Party, by 77,626 votes.

The subsequent chronology of events in the Navjot Sidhu may not be directly relevant to this article but suffice it to say that in 2018, the Supreme Court set aside the High Court’s conviction under “culpable homicide, not amounting to murder” but convicted him under section 323 IPC (simple hurt), with a sentence limited to the imprisonment already undergone and a nominal fine. In 2022, upon review the Apex Court enhanced the sentence to one year and Sidhu, in absence of any remissions, will be completing his sentence in Central Jail, Patiala in May, 2023. Notably, he shall not be suffering from any bar to contest elections in the future, since his sentence was less than two years.

Rahul Gandhi — future eventualities

In summary, an Member of Parliament in India shall be disqualified (lose membership of the House) if they are convicted of an offence and sentenced to imprisonment for two years or more. However, as discussed hereinbefore, there are exceptions to this provision if the conviction and sentence both have been stayed by a superior court. Mr Rahul Gandhi has a limited window of 30 days to seek relief from an appellate court. If such court merely stays his sentence (and NOT the conviction), during the pendency of the appeal, he may stay out of the prison, but would lose the membershipship of Lok Sabha and also incur the 6-year bar from contesting elections in the future. If, however, both the sentence and conviction are stayed during the pendency of the appeal, he shall get a temporary reprieve in respect of all the three issues:

(i) stay out of prison;

(ii) retain his Membership of Lok Sabha;

(iii) not incur the disqualification from contesting in future elections.

Summing up

While we can hardly predict the outcome of his appeal and the nature of the interim relief, if any, that he might get, we can conclude by stating that this event has brought into sharp focus the issue of conviction of MPs and MLAs in criminal cases and the impact of the same on their personal lives and political carriers. The issue of sitting MPs and MLAs, though not convicted but with pending criminal cases will also be drawn into the public discourse, but where every person is presumed to be innocent unless pronounced guilty (convicted) by a competent judicial court, the matter has entirely a different nuance. However, for now all that we can say is that the next 30 days are crucial for Mr Rahul Gandhi himself and the Congress Party. Let’s wait and see.

_________________________________________________________________

The author superannuated as Special Chief Secretary, Punjab in July, 2021, after nearly 37 years of service in the IAS.

He can be reached on kbs.sidhu@gmail.com

Very knowledgeable about constitutional provisions

Shaandar