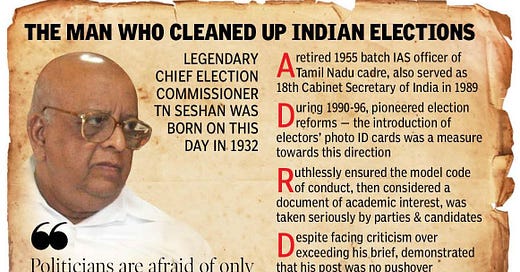

TN Seshan: Exactly 33 Years ago, India's Transformative Electoral Reforms Commenced

My Brush with Late TN Seshan, Chief Election Commissioner of India. The Shadow of the Mighty Seshan on Punjab Elections, in the1990s.

Remembering TN Seshan: 33 Years of Electoral Transformation

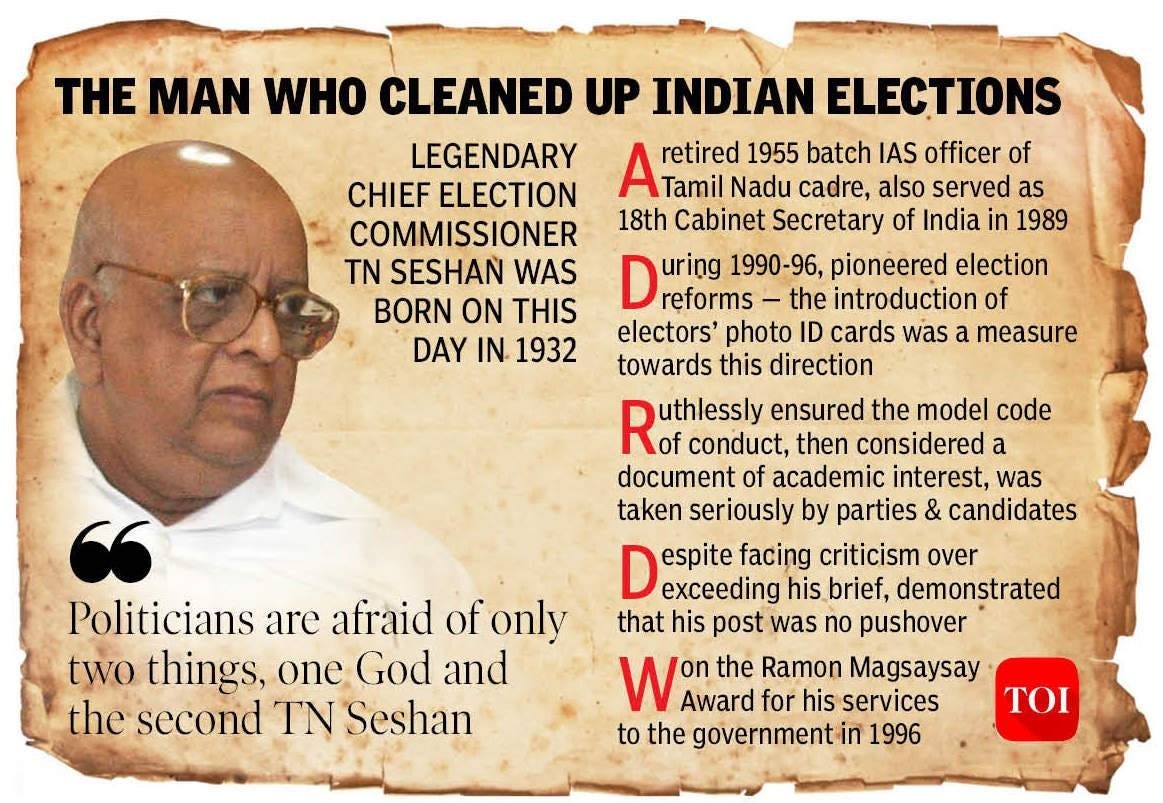

Exactly 33 years ago, on 12th December 1990, Shri TN Seshan assumed the pivotal role of Chief Election Commissioner of India, marking the commencement of a transformative era in the conduct and nature of Indian elections. As we approach the 33rd anniversary of this significant event, and with the 2024 Lok Sabha elections on the horizon, it seems a fitting moment to revisit my reflections penned in shortly after his demise on 10th November 2019. Written from a personal and largely Punjab-centric perspective, this article delves into the profound impact and legacy of Shri Seshan's tenure as the CEC, an impact that resonates strongly even as we gear up for another crucial electoral cycle.

My Brush with Late TN Seshan

TN Seshan, an IAS officer of the 1955 batch of Tamil Nadu cadre was appointed as the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) by late Mr Chandra Shekhar on 12th December, 1990, during his brief tenure as the Prime Minister. Prior to his appointment, the Election Commission of India (ECI) was regarded nothing more than an appendage to the Ministry of Law and was simply a one-member body, with CEC being the personification of the ECI, for all intents and purposes.

TN Seshan as Chief Election Commissioner

Soon after he took over, he gave a wider interpretation, or rather a new meaning, to the Article 324 of the Constitution of India, under which the power of superintendence, direction and control of elections is vested with the ECI. These were plenary powers, he argued, and he arrogated to the Commission powers which were otherwise nowhere to be found in the statute (The Representation of the People Act, 1950 and 1951 or the rules framed there under).

My stint at Amritsar

At that time, as a 1984 batch IAS officer borne on Punjab cadre, I was posted as Additional Deputy Commissioner (Development), Amritsar. Punjab was then under an extended spell of President’s Rule but I had some experience in conducting the 1985 Vidhan Sabha Elections, following the Rajiv-Longowal Accord and thereafter the 1989 Lok Sabha elections, after which Mr VP Singh had become the Prime Minister of India. 1991 was the first time when the Lok Sabha elections were held in the country with Mr Seshan at the helm. Election to the 13 Lok Sabha constituencies in Punjab were, however, not held along with the rest of the country that took place in May, 1991. However, on 21st May, 1991, the PM favourite and former Prime Minister Mr Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated at Sriperumbudur in Tamil Nadu and Mr Sheshan postponed the remaining phases of the Lok Sabha elections immediately. Such postponement was unprecedented but keeping in view the magnitude of the tragedy, no one went into legal niceties, whether the ECI could do so, especially when the election to the Amethi Lok Sabha constituency, from where My Rajiv Gandhi was contesting, had already concluded in an earlier phase. We received this tragic news in Amritsar around noon, during the peak of the Punjab summer. Everyone was stunned but, I must confess, there was an underlying but unstated sense of relief that there was no “Punjab-angle” to the assassination[1]. After a few days, the polling to the remaining phases was concluded peacefully and in the case of Amethi, counting went on as usual and after Late Rajiv Gandhi was found to have polled the maximum number of votes, he was notionally declared elected and simultaneously, the seat declared as vacant on account of the demise of Mr Rajiv Gandhi, paving way for by-election subsequently. As events unfolded, Mr PV Narsimha Rao formed a Congress-lead minority Government in the country.

The aborted Punjab Election of 1991

The Narsimha Rao Government had different take on the Punjab situation. Rather than waiting for normalcy to be restored, it took the view that the situation in the State would improve only when democratic institutions, including the Punjab Vidhan Sabha, were restored. Decision was taken to hold the Vidhan Sabha elections in Punjab in June, 1991. General OP Malhotra, the retired Army Chief, was the Governor of Punjab and the election process saw dozens of validly nominated candidates being gunned down by terrorists, leading to the countermanding of elections in a number of constituencies. However, as dusk fell on 20th June, 1991, the people went to sleep in an atmosphere of uneasy calm but also hope that the polling would finally commence in less than 36 hours[2].

Next morning, Mr Seshan announced that the elections had been postponed, something which the law did not expressly permit, at least not on omnibus basis. We had been taught that once the Notification for the conduct of elections had been issued, nothing short of a natural calamity of national dimensions could derail the election process. The Governor General OP Malhotra resigned in protest but eventually the entire blood-stained, inchoate election process was scrapped by promulgating an ordinance to amend the relevant law.

Towards Punjab Elections in February 1992

Thereafter, with a retired IPS Officer, Mr Surendra Nath, as the Governor of Punjab, the Narsimha Rao Government decided to hold elections in Punjab in February, 1992. The militant organisations gave a call for these elections to be boycotted and the mainstream Akali Dal(s) also chose to abstain. Nevertheless, TN Sheshan steered these elections relatively peacefully, although the poll-percentage was only around 10%. In fact, in some rural constituencies, especially in the border belt, the polling was as low as 5%. I, as Additional Deputy Commissioner (Development), Amritsar was also the Returning Officer of Jandiala Vidhan Sabha constituency. The conduct of election was tough but the process was essentially peaceful. We did not even have an Fax machine in our office and I clearly recall that established industrialists declined our request to use their Fax machines to send our request to the ECI, seeking its permission for the declaration of the result — such was the atmosphere of terror. These elections saw the Congress party securing a huge majority and Sardar Beant Singh became the Chief Minister of Punjab.

Democracy at the Grassroots

Sardar Beant Singh, as Chief Minister, held the Municipal Council elections in September, 1992 and Gram Panchayat elections in January, 1993. The turnout in these was very handsome and these were largely seen as free and fair, by even the international media that descended onto Amritsar district. Although ECI and Mr Seshan were not directly involved, but the District Administration, by and large, followed the practices and protocols of the ECI in these elections as well. I am firmly of the opinion that the return of democracy was a tilting factor in the quick return of normalcy in the border State of Punjab, which had seen disturbed conditions for decades.

Face-to-face with TN Seshan, as Deputy Commissioner Amritsar

In the meanwhile, I was elevated to the post of Deputy Commissioner, Amritsar in May, 1992. Around this time, Mr TN Seshan had convened at meeting of about fifty odd District Election Officers in New Delhi to discuss some of his proposed reforms. Amritsar district was one of those selected. I reached New Delhi a day in advance and was at the venue well before the designated time. At the stroke of 11.00 AM, the man lumbered in — there was pin-drop silence. Mr Seshan started speaking in a most business-like manner and barely seconds later, a District Magistrate from UP slid in. “What makes you think that you can walk in like this, without permission, once the meeting has commenced?” The poor man expressed his profuse apologies and tried to explain that the taxi-driver could not find the right way. “If you cannot manage your trip to the Commission properly, how can you manage your district smoothly? You are hereby relieved from your duties as the District Election Officers. Now GET OUT!!”, he thundered. After a meak expostulation, the poor chap had to leave the meeting hall ignominiously. What became of him in his State, one doesn’t really know.

Mr TN Seshan went on to observe that the agenda of the meeting had been leaked and that a National Daily had quoted from it verbatim in its story appearing on the very day of the meeting, with the dateline of a district headquarter in Haryana. He took two representatives from Haryana to task and threatened to get a criminal case registered under the Official Secrets Act. When they vehemently pleaded their innocence, his wrath got shifted to his own officers, who he squarely blamed for this “major lapse”. Somehow, they cooled him and after that the meeting went on in graveyard-like silence with none but Mr Seshan speaking. No one volunteered any answer when he posed a general question. He was not really interested in any replies and never asked any officer pointedly for their opinion. This meeting only reinforced the general impression that it’s best not to say anything in his presence.

Ajnala bye-election

Ajnala Vidhan Sabha constituency in Amritsar district had been represented by Sardar Harcharan Singh Ajnala since February, 1992 and he had also been elected as the Speaker of Vidhan Sabha. After his unfortunate demise in June 1993, stage was set for a bye-election, which got scheduled to be held in the summer of 1994.Ajnala and Nikodar in Jalandhar district became the focus of attention of all political parties as these were seen to be the litmus test for the Beant Singh Government, which had otherwise been dubbed by its detractors as “non-representative” on account of the abysmally low turnout.

The bye-election has postponed on account of heavy rains and floods in the June-July, 1994, which also operated to extend the “Code of Conduct”. It was a tooth and nail fight between the Congress Party and the Akali Dal, whose chief Sardar Parkash Singh Badal, had made it a matter of personal prestige. The Beant Singh Government was also keen to demonstrate its legitimacy. The entire process took place under the ever-watchful eyes of Mr TN Seshan and two Observers that the ECI had appointed. The Akali Dal candidate won by over ten thousand votes in Ajnala, while Congress was victorious in Nikodar. The Conduct of the Ajnala bye-election, in a free and fair manner, was appreciated not only by the ECI but by the Chief Minister, late Mr Beant Singh himself, since the District Administration did not buckle under the pressure from either side in the high-stakes contest.

Seshan in Amritsar?

During the canvassing period of the Ajnala by-polls, Mr TN Seshan announced his plan to visit Amritsar. He was to travel by train. Those were the days before the era of ubiquitous mobile phones. The major issue was being at the right bogie and at the right exit door to receive him, as the train would arrive at Amritsar. His staff refused to divulge his Bogie Number/ Seat Number, on “security grounds”. The Chief Electoral Officer, Punjab arrived a day in advance and after hearing about the taxi-driver episode of my New Delhi meeting, was convinced that we would both be sacked, unless we were there at the exact spot of the platform, where his bogie came to a halt, to receive him. He was not willing to leave it to the local Railway Officers to let us know about his location. It was accordingly decided that two gazetted officers — one from magistracy and the other from police — would board the same train at Jalandhar and discreetly ascertain the location of Mr Seshan and signal it to us from the very same bogie in which Mr Seshan would be travelling. Lengthy briefing of the officers, along with the officers of the Indian Railways took place a day in advance but we got happy tidings by the evening — the Seshan visit had been cancelled, bringing huge relief to all of us, especially the Chief Electoral Officer, who, alas, is no more. He really dunked more than a few pegs of whiskey as we sat for dinner in the DC residence, to get rid of the piled up tension (I was then a teetotaler).

Amritsar, as indeed the whole of Punjab had been pretty much normal since the middle of 1994, but the assassination of the Chief Minister, Sardar Beant Singh, outside the high-security Punjab Civil Secretariat at Chandigarh on 31st August, 1995, sent a rude shock to those who were being complacent. It reminded us that we should not be lulled into the notion of false security. Sardar Harcharan Singh Brar, who was sworn in as the next Chief Minister, continued as such till 21st November, 1996, before he was replaced by Mrs Rajinder Kaur Bhattal.

Lok Sabha Elections of 1996

By the time, the 1996 Lok Sabha elections came in the peak of summer, I had already completed four years as Deputy Commissioner, Amritsar. I had a different level of confidence and experience and was not apprehensive about being chucked out for any lapse, real or imaginary. I had already been slotted by the Government of India for a 1-year MA (Economics) course at the University of Manchester, UK. Moreover, the Lok Sabha elections, sans the Vidhan Sabha polls are far less intensive and contentious. I must say our team conducted the election to Amritsar and Tarn Taran Parliamentary constituencies with quite efficiency and aplomb. As a matter of fact, DC Amritsar had the unique distinction of being the Returning Officer for two parliamentary constituencies (Tarn Taran was carved out as a revenue district much later).

Army to assist in Elections?

Two incidents are worthy of narration here. There was a longish gap between polling and counting, as Punjab had been covered in the initial Phase of Polling. The ballot boxes of Tarn Taran Parliamentary constituency were stored at a centralized location, with round-the-clock Punjab Police security. There was apprehension that attempts may be made to tamper with the same, in connivance with the local police officers. I accordingly requested for deployment of Central Paramilitary Forces. This request was declined on the ground that the forces were already committed for movement and deployment in other parts of the country where polling had yet to take place. I accordingly informed the Chief Electoral Officer that I intended to requisition the Army to secure the centre where the ballot boxes were stored. Leading newspapers also carried the story. This caused a major ruffling of feathers in both Chandigarh and New Delhi. I was told that the election code did not permit such deployment and also that requisition of Army would send a wrong signal to the international community that the situation in Punjab was getting out of control again. I stated that the election code may not permit it but as the District Magistrate, I was duly empowered under the Code of Criminal Procedure to make such a requisition, at least to secure the outer perimeter.

Plot to ease me out of Amritsar

On instructions of Mr Seshan, the Chief Electoral Officer rushed to Tarn Taran and ultimately a compromise decision was taken to deploy India Reserve Battalions of Punjab Police instead of the local police. During this interregnum, some disgruntled candidates also submitted to the ECI that I had completed more than five years as DC and Additional DC combined and as such I such be transferred out forthwith. Having conducted the elections smoothly, I did not want to exit at this stage on a stigmatic note. Direct access to Mr Seshan was virtually impossible but I was able to get through to Mr Manohar Singh Gill, a retired Punjab cadre IAS officer, who was now working as Election Commissioner (ECI had since become a multi-member body). Mr Gill, himself from Tarn Taran, knew the credentials of the complainants as well as my track record and the move to shunt me out was nipped in the bud.

Two Prime Ministers in a fortnight

The counting has smooth — the elections threw up a hung Lok Sabha. Mr Atal Bihari Vajpayee was sworn in as the PM, being the leader of the single largest Party. He remained in office for 13 days but resigned before the vote of confidence but not before flying over to Amritsar to pay obeisance at the Golden Temple at Amritsar. The next PM, Mr HD Deve Gowda also flew to Amritsar for a similar pilgrimage. I had the privilege of receiving both of them personally at the airport and escorting them throughout their short sojourn to the Holy City.

Academia — University of Manchester, UK

By late August, 1996, I was in Manchester, UK, away from the dust and din of Punjab politics. Mr TN Seshan demitted office on 11th December, 1996 and was succeeded by Mr MS Gill as the CEC. Punjab has headed for election in February, 1997 but I was working hard on my academics in cooler climes of England.

TN Seshan RIP

When I heard the news of his demise on 10th November, 2019, the events of the 1990s flashed past me. I bowed by head in reverence to the man who had single-handedly changed the form and substance of the Election Commission of India and left his “indelible” impression (pun intended) on the electoral landscape of world’s largest and greatest democracy. TN Seshan RIP.

Epilogue

Every Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) or Election Commissioner (EC) entrusted with these esteemed constitutional offices must strive to not only uphold the Constitution of India and its laws but also to meet the lofty standards set by the late TN Seshan. These are the expectations of the citizens of India, a testament to the robustness of our democracy. Whether these office bearers fall short or choose not to uphold these standards, the discerning citizens of our great nation will invariably take note. To those currently in position, the timeless wisdom of Shakespeare rings true: “To thine own self be true.”