Still Seeking Justice: British Reluctance to Apologise for the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

The British government’s repeated refusal to apologise reflects not just legal caution, but a broader reluctance to confront the ethical dimensions of its colonial past.

A Century of Silence and Sorrow

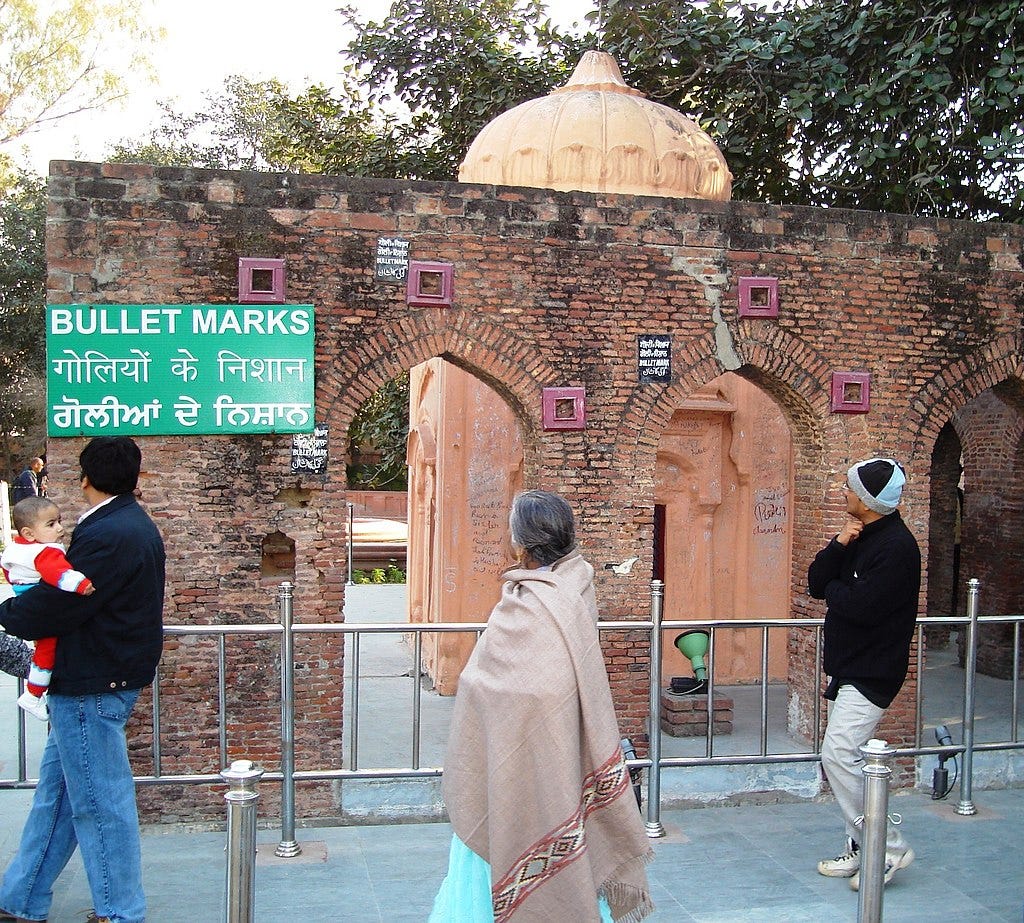

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 13 April 1919 remains one of the most harrowing and indelible stains on British colonial rule in India. Today, as we commemorate the 106th anniversary of that unspeakable atrocity, the memory of that blood-soaked afternoon in Amritsar continues to evoke pain, pride, and an enduring call for justice. While successive British leaders have expressed sorrow and “deep regret”, they have consistently stopped short of offering a formal apology—a calculated diplomatic evasion that is as revealing as it is frustrating.

Notably, while former Rajya Sabha MP Sardar Tarlochan Singh has raised the demand for an apology on multiple occasions, the issue has never found a place on the priority agenda of the Government of India—even during the tenure of Rishi Sunak, the UK’s first Prime Minister of Indian origin. This article examines the political hesitations of British governments, the symbolic gestures of Queen Elizabeth II, the narrow legal avenues available to the victims’ descendants—and the fierce, unforgettable patriotism of one man who refused to let the world forget: Shaheed Udham Singh.

Regret Without Responsibility: The Calculated Diplomacy of British Leaders

British government responses to the massacre have carefully balanced historical acknowledgment with a legal and diplomatic strategy aimed at avoiding liability. Although there has been moral recognition of the event’s horrors, there remains an intentional avoidance of language that could be construed as legal responsibility—likely to prevent reparation claims and the setting of unwelcome precedents.

Theresa May’s Carefully Worded Statement

Marking the centenary of the massacre in 2019, then Prime Minister Theresa May described Jallianwala Bagh as a “shameful scar” on British-Indian history and expressed “deep regret”. However, her remarks stopped short of offering the unequivocal apology that many Indian leaders and campaigners had sought. Speaking in the House of Commons and later at a Vaisakhi event at Downing Street, May repeated sentiments of sorrow, but without stepping into the domain of formal apology.

Strategic Concerns Behind the Silence

The reluctance to apologise stems from multiple strategic considerations:

Legal Liability: A formal apology might be interpreted as an admission of legal culpability, potentially exposing Britain to reparation demands from across its former empire.

Diplomatic Precedent: UK Government officials have voiced fears that a single apology could trigger a “hornet’s nest” of similar claims from other nations.

Devaluation of Apologies: As UK junior foreign minister Mark Field once noted, there is concern that the currency of apologies is devalued when issued too freely or frequently.

This strategic posture reflects a broader trend among former colonial powers: symbolic remorse, carefully separated from legal accountability.

The Flame of Justice: Shaheed Udham Singh’s Heroic Response

If Jallianwala Bagh was a wound on the Indian soul, then Shaheed Udham Singh was the enduring flame of remembrance and retribution. A survivor of the massacre, he carried the trauma and rage of a brutalised nation in his heart for over two decades. On 13 March 1940, in London’s Caxton Hall, Udham Singh shot and killed Michael O'Dwyer—the former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab who had defended General Dyer’s brutal action.

Udham Singh’s act was not one of mere vengeance; it was a conscious, revolutionary act—a clarion call for justice. At his trial, he boldly declared: “I am not afraid to die. I am proud to die to free my native land, and I hope that when I am gone, my work will go on.” His words rang not only in that British courtroom but across generations of Indians who would draw inspiration from his resolve.

Even today, Shaheed Udham Singh stands as a towering symbol of patriotic sacrifice. While Britain may continue to sidestep a formal apology, the memory of this fearless martyr reminds the world that colonial brutality was neither forgotten nor forgiven. His sacrifice was not driven by hatred, but by an unyielding love for his people, his country, and the dream of an India free from oppression.

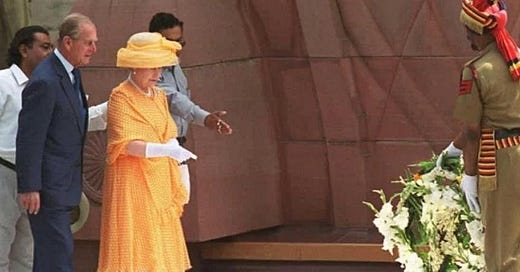

Royal Gestures: Queen Elizabeth II’s Visit to Amritsar

In 1997, during the 50th anniversary of India’s independence, Queen Elizabeth II paid a historic visit to the Jallianwala Bagh memorial in Amritsar. While the visit was laden with symbolism, it too fell short of issuing a formal royal apology.

Symbolism Over Substance

At the site, the Queen removed her shoes in keeping with Indian custom and laid a wreath in solemn tribute to the victims. In her state banquet speech in New Delhi, she described the massacre as a “distressing example” of Britain's colonial past, expressing sorrow but again avoiding language that would imply culpability.

Observers noted a symbolic inconsistency: while the Queen walked barefoot at Jallianwala Bagh, she wore socks during her visit to the Golden Temple. This detail stirred mild controversy and served as a reminder of the deep sensitivities still attached to Britain's imperial legacy in India.

A Missed Opportunity?

Despite her gestures of remembrance, many in India regarded the visit as a missed opportunity. Without a formal apology, it was seen as yet another instance of Britain stopping short of full moral reckoning.

The Elusive Path to Legal Redress

The descendants of the massacre victims have few viable avenues for legal justice. International legal frameworks offer limited options, burdened by procedural barriers and philosophical complexities.

Legal Hurdles to Reparation Claims

Several challenges stand in the way of successful reparation efforts:

Statute of Limitations: Most jurisdictions impose strict time limits on legal claims, long surpassed in this case.

Principle of Intertemporality: International law requires actions to be judged according to the laws prevailing at the time they were committed, not by modern standards.

Intergenerational Standing: It is legally unclear whether descendants of victims have the standing to seek compensation for historical injustices.

Quantifying Damages: The economic and emotional toll of such an atrocity is nearly impossible to measure after more than a century.

Transitional Justice and Symbolic Remedies

Some scholars advocate for transitional justice approaches—truth-telling, public recognition, and reconciliation—as more effective and meaningful alternatives to financial compensation or legal remedies. These non-monetary forms of reparation may serve the deeper purpose of healing national memory.

Precedents and Limitations

There are few legal precedents. A notable exception is the 2013 settlement between the British government and Kenyan survivors of the Mau Mau uprising. However, this case proceeded through the British legal system and did not establish a broader precedent for reparations via international courts, which generally require state consent and rarely permit individual claims.

Conclusion: Memory, Martyrdom, and the Moral Reckoning

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre continues to cast a long, unresolved shadow over British-Indian relations. The British government’s repeated refusal to apologise reflects not just legal caution, but a broader reluctance to confront the ethical dimensions of its colonial past. Queen Elizabeth II’s visit offered symbolic acknowledgment, but fell short of the moral closure many continue to seek.

More than a century after the bloodbath in Amritsar, India still remembers not only the hundreds who perished but also the one who refused to forget—Shaheed Udham Singh. His fiery commitment to justice stands in stark contrast to Britain’s cautious diplomacy. He reminds us that while an empire may try to bury its sins under silence, the conscience of a nation—fuelled by courage, sacrifice and memory—cannot be so easily extinguished.

Justice delayed may be justice denied, but the demand for it echoes still. Until that demand is met with sincerity, the wounds of Jallianwala Bagh will remain open, not just in history books, but in the hearts of the people.

Jallianwala Bagh: Commemorating the Anniversary and Reflecting on the Echoes of the 1919 Amritsar Massacre

Reflecting on Historical Shadows and Contemporary Challenges

ਵਾਹਿਗੁਰੂ ਜੀ ਕਾ ਖਾਲਸਾ ਵਾਹਿਗੁਰੂ ਜੀ ਕੀ ਫਤਿਹ

ਖਾਲਸਾ ਜੀ ਦੇ ਸਾਜਨਾ ਦਿਵਸ ਦੀਆਂ ਆਪ ਜੀ ਨੂੰ ਬਹੁਤ ਬਹੁਤ ਮੁਬਾਰਕਾਂ ਜੀ।

ਸਿੱਧੂ ਸਾਬ

ਇੰਗਲੈਂਡ ਦੀ ਸਰਕਾਰ ਜੇ ਹੁਣ ਮੁਆਫੀ ਮੰਗ ਵੀ ਲਵੇ ਤਾਂ ਵੀ ਇਸ ਸਾਕੇ ਦੇ ਦਰਦੀਆਂ ਦਾ ਦਰਦ ਘਟੇਗਾ ਨਹੀਂ। ਚਾਹੀਦਾ ਤਾਂ ਇਹ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਇਸ ਨਰਸੰਘਾਰ ਦੇ ਪ੍ਰਭਾਵਿਤ ਲੋਕਾਂ ਦੇ ਪ੍ਰੀਵਾਰਾਂ ਦੀ ਮਾਲੀ ਮਦਦ ਕੀਤੀ ਜਾਵੇ ਅਤੇ ਉਹਨਾਂ ਪ੍ਰੀਵਾਰਾਂ ਦੇ ਮੌਜੂਦਾ ਮੈਂਬਰਾਂ ਦੀ ਪਹਿਚਾਣ ਕਰਕੇ ਇੱਕ ਯਕਮੁਸ਼ਤ ਯੋਜਨਾ ਬਣਾਈ ਜਾਵੇ। ਮੁਆਫੀ ਮੰਗਣ ਨੂੰ ਵੀ ਭਾਰਤੀ ਹਕੂਮਤ ਆਪਣੀ ਪ੍ਰਾਪਤੀ ਦੇ ਪ੍ਰਚਾਰ ਲਈ ਹੀ ਵਰਤੇਗੀ ਬੱਸ ਹੋਰ ਕੋਈ ਫ਼ਰਕ ਨਹੀਂ ਪੈਣਾ

ਨਿਸ਼ਾਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਕਾਹਲੋਂ

https://x.com/skamaraj32/status/1651479176866611202?s=46