Srinagar Now on the Right Track: The Real Story is the Train, Not Just the Bridge

Broad-Gauge Rail Finally Connects Kashmir Valley to the Indian Mainland—The Chenab Bridge Is a Marvel, But Integration Is the Milestone.

By Karan Bir Singh Sidhu

Retired IAS Officer (Punjab Cadre), Former Special Chief Secretary, Government of Punjab

Writer, Policy Commentator, and Advocate for Constitutional and Strategic Integration

Direct Rail to the Valley: Srinagar’s First Broad-Gauge Link

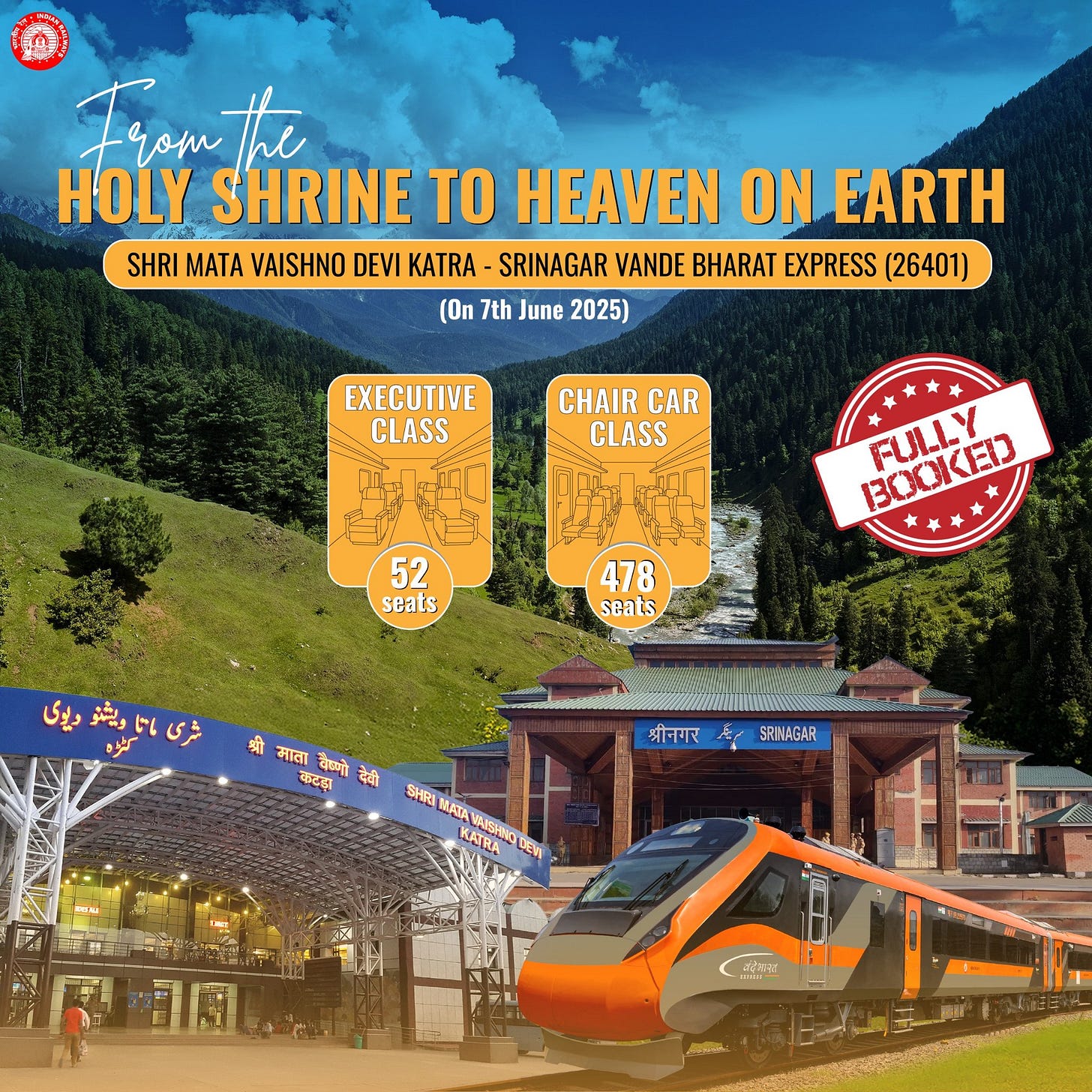

For the first time since Maharaja Pratap Singh dreamed of a railway in the 1890s, a passenger can board a train in the Kashmir Valley and remain on the same broad-gauge network all the way to Kanyakumari. The breakthrough became reality on 7 June 2025, when Vande Bharat Expresses began running daily between Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Katra and Srinagar, shrinking a day-long road ordeal to a three-hour glide through tunnels and across sky-high viaducts.

The new services operate as follows:

Train 26401 departs Katra at 8:10 a.m., halts at Banihal by 9:58 a.m., and reaches Srinagar at 11:08 a.m. (every day except Tuesday).

Train 26402 leaves Srinagar at 2:00 p.m., stops at Banihal at 3:10 p.m., and arrives in Katra at 4:58 p.m. (every day except Tuesday).

Train 26404 begins its journey from Srinagar at 8:00 a.m., reaches Banihal by 9:02 a.m., and pulls into Katra at 10:58 a.m. (every day except Wednesday).

Train 26403 departs Katra at 2:55 p.m., stops at Banihal at 4:40 p.m., and concludes at Srinagar by 5:53 p.m. (every day except Wednesday).

These winter-hardened Vande Bharat trains are custom-built with anti-freeze pipes, heated gangways, snow-resistant brakes and panoramic windows—perfect for the Valley’s climate and for the iconic three-minute sweep over the Chenab Bridge.

A Flag-Off from the Clouds

A day before full operations began, on 6 June 2025, Prime Minister Narendra Modi stood at the edge of the Chenab gorge, unfurled the Tricolour, and remotely flagged off the service that finally bridged India’s northernmost region with its national rail grid. “Bharat’s handshake with the Himalayas,” he declared, as the test rakes crossed the world’s highest railway arch. This final 63-kilometre link of the Udhampur–Srinagar–Baramulla Rail Line (USBRL) was the last piece in a 272-km puzzle that had tested engineers, governments, and generations of public will.

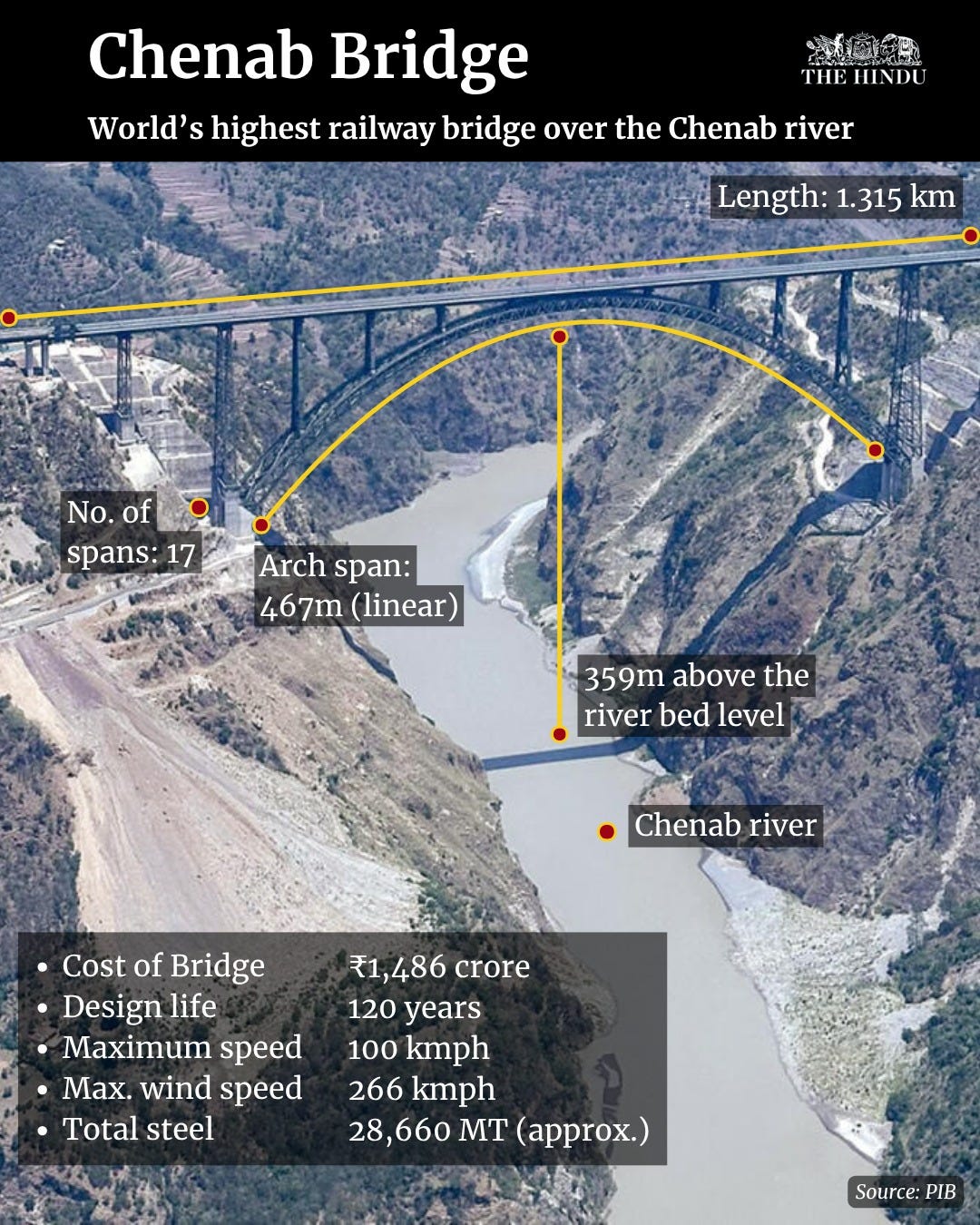

Engineering Wonder of the Chenab: More than a Pretty Arch

At 359 metres above the Chenab River—thirty-five taller than the Eiffel Tower—the eponymous bridge is an engineering marvel that now graces the covers of engineering journals and patriotic posters alike. Its 467-metre twin-rib arch, joined mid-air after precision cantilevering from both banks, supports a kilometre-long deck built to withstand seismic shocks, wind speeds of 266 km/h, and even 40 kg TNT blasts.

The bridge required 28,660 tonnes of steel and includes innovations such as Swiss spherical bearings, real-time health monitoring systems, and a five-layer corrosion-resistant coating designed to last 15 years per cycle. From the south, trains descend gracefully onto the arch, skim its span in under three minutes, and disappear into Tunnel T-3—an engineering ballet carved into a formerly inaccessible landscape.

Decades of Determination: The Long Road to USBRL

What began as a concept in 1983, got sanctioned in 1995, and was declared a national project in 2002, finally reached completion in 2025. This project has survived insurgency, war, geological uncertainty, and political change. Workers slept in CRPF camps, used helicopters to ferry steel, and fought against the unstable Murree rock formation.

Phase by phase, the dream progressed: Baramulla–Qazigund opened under Dr Manmohan Singh; Katra–Banihal was pushed under Vajpayee; and the final Sangaldan–Katra segment was completed under Prime Minister Modi. Costing over ₹44,000 crore, USBRL stands as the most expensive and ambitious mountain railway ever built in India.

Parallel Highways Beneath the Peaks

While rail engineers fought rock with rail, road builders attacked the Himalayas with asphalt. The Chenani–Nashri Tunnel (10.9 km) shortened NH-44 by forty kilometres. The Atal Tunnel (9.02 km) breached Rohtang’s winter barrier. The Z-Morh and Zojila tunnels, still underway, are set to bring all-weather connectivity to Ladakh. Together, these projects turn geography from a barrier into a bridge.

Strategic and Economic Winds of Change

A three-hour journey between Katra and Srinagar now unlocks tremendous strategic and civilian benefits:

Pilgrims can complete their yatra to Vaishno Devi and Amarnath in a single day.

Apple growers and artisans gain a refrigerated, efficient supply chain.

Students and job seekers have uninterrupted access to India’s educational and economic heartlands.

Defence logistics are now rapid, efficient and less dependent on vulnerable convoys.

Political Continuity, Credit of Completion

Prime Minister Modi’s flag-off marked the final, most visible achievement—but credit is due across the political spectrum. P. V. Narasimha Rao sanctioned the project, Vajpayee gave it national project status, Manmohan Singh opened key phases, and Modi brought it home. It is rare that a public project embodies true political continuity; USBRL is one of those rarest of success stories.

Connectivity Beyond Concrete

If the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 consummated the constitutional integration of Jammu and Kashmir with the Union of India, the seamless broad-gauge railway line now delivers its physical, commercial, and emotional integration. The symbolism is as profound as the steel is strong.

We no longer need to qualify Jammu and Kashmir as an “integral part” of India. What is already a part and parcel of the Republic does not need an adjective to validate its belonging. Trains now carry people, produce, and possibilities—collapsing old distances, not only geographic but psychological. This isn’t just about connectivity—it is about cohesion forged in iron and will.

Conclusion: Tracks Through Time

The Chenab arch will grace textbooks and tourist posters, but the real story is the soft hum of wheels on broad-gauge rail echoing through once-silent gorges. In under four hours, a traveller can now leave the plains and arrive in Srinagar—an astonishing testament to India’s capacity to mine, weld, and tunnel through granite, geopolitics and generations of doubt.

Kudos to Prime Minister Modi for turning blueprint into bridge, and a measured salute to those who kept the dream alive across four decades. From idea to iron, from aspiration to acceleration—the journey has been long. But the lifeline it laid is built to last.

The Chenab Bridge is more than a structure of steel and stone; it is a bridge that unites, integrates, and connects—in more ways than one, both literally and metaphorically. It binds regions, hearts, and horizons. It carries not just trains, but the weight of history, the movement of commerce, and the momentum of a shared future. And in doing so, it affirms—quietly yet powerfully—that Jammu and Kashmir is not at the periphery of the Republic, but firmly on its path, platform and pulse.

From a security and maintenance standpoint, it could be one of the most expensive piece of infrastructure. However, this bridge stands tall to meet the economic needs of people in the valley, on economic, social and political fronts. Hope in near future, Railways launch direct trains from Srinagar to all major metros like Chennai, Bangalore, Mumbai, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Delhi and connect all important business and economic locations.

Timely completion of projects has been a big challenge in India, although current govt in Centre is doing well on this front. It will be of great help if data related to costs by important variables, like labour, materials (imported vs local), time overruns, etc is shared.