Restoring the Say of Sehajdhari Sikhs: A Constitutional and Religious Imperative for Inclusive Gurdwara Governance

A newly elected General House—one that includes the voices and votes of Sehajdhari Sikhs—can take decisions that are fair, just, and rooted in the collective conscience of the Panth.

Hearing on Sehajdhari Sikh Petition Adjourned in Punjab and Haryana High Court

The Civil Writ Petition filed by the Sehajdhari Sikh Party challenging the constitutional validity of the 2016 amendment to the Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925, came up for hearing before the Punjab and Haryana High Court but was adjourned to 26 May, 2025. The hearing was deferred as the Chief Justice was away in New Delhi, serving as a member of the Supreme Court-appointed committee probing the high-profile burnt currency incident involving a sitting judge of the Delhi High Court.

Speaking exclusively to ‘The KBS Chronicle’, the National President of the Party and lead petitioner, Dr Paramjeet Singh Ranu, asserted that his Party, which is duly registered with the Election Commission of India, would press for an early decision. He emphasised that the SGPC elections—last held in 2011—are now imminent, yet over 70 lakh Sehajdhari Sikhs remain disenfranchised owing to the retrospective amendment pushed through Parliament in 2016 at the behest of the then Punjab Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal. This amendment overturned a landmark ruling of the full bench of Punjab and Haryana High Court which had earlier quashed a Central Government notification and restored Sehajdhari voting rights—valuable rights that had existed since Independence. The amendment, Dr Ranu contended, undid the justice delivered by the Hon’ble High Court and compelled the petitioners to seek legal redressal yet again.

I. Jurisdictional Overreach: Parliament vs State Competence

The 2016 amendment raises a critical jurisdictional issue. In the context of the Supreme Court’s ruling upholding the constitutional validity of the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Management Act, 2014, it is now been authoritatively established by that management of religious institutions falls within the domain of state legislation under Entry 32 of the State List. The Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925—despite being a pre-Independence statute—is for all practical purposes a state law. Therefore, the retrospective amendment by Parliament appears to be ultra vires, breaching the federal structure enshrined in the Constitution.

II. The SGPC and Its Historical Evolution

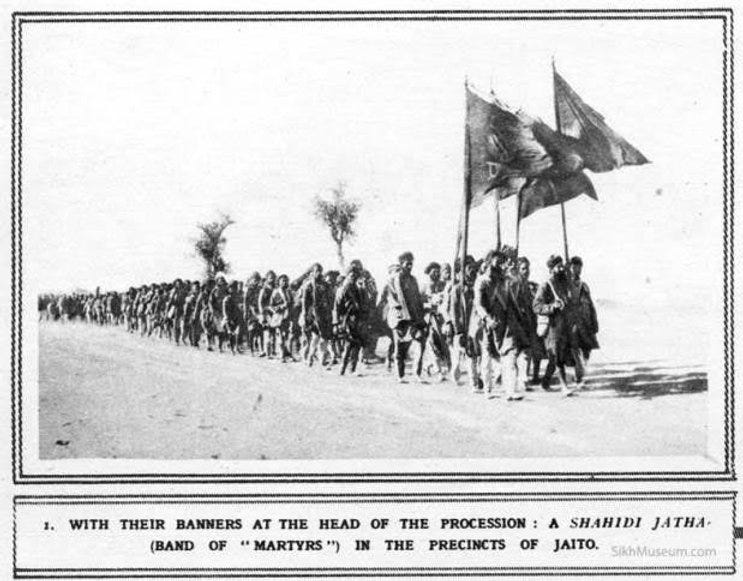

Emerging from the Gurdwara Reform Movement of the 1920s, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) was initially a voluntary society formed to reclaim gurdwaras from the clutches of corrupt mahants. The movement gained moral traction after the tragic Nankana Sahib massacre. In 1925, the Sikh Gurdwaras Act gave statutory recognition to the SGPC, marking a significant shift towards democratic religious governance, a very rare feature in the colonial era.

III. Definitional Framework of Sikh Identity

The Act carefully defines various categories of Sikhs—Sikh, Amritdhari Sikh, Sehajdhari Sikh, and Patit—thereby capturing the complex spectrum of Sikh identity. The Sehajdhari Sikh, in particular, is not a peripheral figure but a devout adherent who may be born within or outside the faith but follows its tenets, abstains from tobacco and halal meat, performs Sikh rituals, and can recite the Mul Manter. These are not casual identifiers; they denote deep religious commitment.

IV. Historical Voting Rights of Sehajdharis

Since 1947, Sehajdhari Sikhs had the right to vote in SGPC elections, although only Amritdharis could contest. This arrangement ensured broad-based participation in the management of Sikh institutions, while the actual governance was in the hands of the Amritdhari leadership. Their disenfranchisement—first attempted via a 2003 executive notification and later cemented by the 2016 legislative amendment—has disrupted this long-standing inclusive model, based not only on the inclusive and long-established practice but also the core principles of Sikhism and the timeless teachings of the Sikh Gurus.

V. The 2003 Notification and the High Court's Intervention

The Centre’s 2003 notification, issued under Section 72 of the Punjab Reorganisation Act, 1966 sought to remove Sehajdhari voting rights. However, in December 2011, a full bench of the Punjab and Haryana High Court quashed the notification as legally untenable. The Bench noted that a valuable legal right could not be taken away by executive fiat, even if the notification was ostensibly a statutory one. This judgment briefly restored the franchise to Sehajdhari Sikhs—only to be annulled by the 2016 amendment.

VI. The 2016 Amendment: Hasty and Unjust

The Sikh Gurdwaras (Amendment) Act, 2016, passed retrospectively and without adequate parliamentary debate, effectively reversed the High Court’s decision. Bunched with unrelated legislation and overshadowed by the Aadhaar Bill, the amendment deprived millions Sehajdhari Sikhs of their right to participate in SGPC elections. Its retrospective nature, dating back to 8 October 2003, raises serious questions about its legality and fairness.

VII. Shrinking Electorate and Crisis of Representation

The consequences are visible: voter registration has declined from 52 lakh in 2011 reportedly to approximately 45 lakh now, despite natural population growth. The SGPC, once representative of the diverse Sikh community, is increasingly seen as a body dominated by a narrow orthodoxy, that acts in in accordance with narrow personal, political and parochial considerations. This undermines its legitimacy in the eyes of many practising Sikhs, especially among the youth who have reached voting age since 2011.

VIII. Article 25 and Minority Rights

The amendment also violates Article 25 of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of religion, and Articles 29 and 30, which protect minority rights, especially those of the religious and linguistic minorities. Denying Sehajdhari Sikhs—who follow the Sikh religion and have no other religious affiliation—the right to vote in their religious body's elections is a clear infringement of their Fundamental Rights, enshrined in inviolable constitutional provisions.

IX. The Question of Jathedar Appointments

The fallout of this disenfranchisement is most evident in the contentious appointments of the Jathedars, including that of the Sri Akal Takht Sahib. The current SGPC Executive Committee, drawn from a 2011 General House, lacks the moral and democratic authority to make decisions that affect the global Sikh community. A newly constituted General House, inclusive of Sehajdhari voters, could restore credibility and fairness to these appointments.

X. Sehajdhari Sikhs: Sikhs in Faith, Not Form Alone

The principal distinction of Sehajdhari Sikhs lies in their non-observance of certain external symbols, particularly unshorn hair. Yet in belief, daily practice, and moral commitment, they remain deeply embedded within the Sikh tradition. It is argued on their behalf that neither Sri Guru Granth Sahib nor the teachings of the Sikh Gurus explicitly mandate the maintenance of uncut hair as a strict precondition for religious legitimacy. At most, this requirement appears to be a construct of the colonial era or a codification under the Rehat Maryada later framed by the SGPC—one which, significantly, remains in draft form and has not been formally adopted by the General House of the SGPC in consultation with the wider Sikh community, including institutions, scholars, and religious organisations. Their exclusion from Gurdwara governance, therefore, lacks both scriptural sanction and theological justification.

XI. Safeguarding Sikh Autonomy from Political Overreach

Unchecked parliamentary intervention in religious matters, as seen in the 2016 amendment, threatens the autonomy of Sikh institutions. The SGPC, a hard-won legacy of the Akali movement and the Gurdwara Reform Movement, must be protected from becoming a political pawn. Ensuring the legitimate rights of all practising Sikhs—Sehajdhari or otherwise—is essential for preserving its sanctity and relevance.

XII. Historical and Emotional Significance: A Covenant Forged in Sacrifice

The Sikh Gurdwaras Act holds profound historical and emotional significance for the Sikh community. In the tumultuous years leading up to Partition, the Sikh leadership—under the stewardship of Master Tara Singh—rejected Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s offer to join Pakistan and chose instead to remain with India. This was not a decision taken lightly, as it came at the cost of incalculable loss of lives, land, and property during one of the most painful upheavals in the subcontinent’s history. Yet this choice was anchored in a firm belief that an independent India would safeguard the religious identity, institutional autonomy, and democratic traditions of the Sikh Panth. The Sikh Gurdwaras Act of 1925 stood at the heart of this assurance. More than just a piece of legislation, it symbolised a solemn covenant between the Sikh community and the Indian state—a promise that the community’s sacred institutions would be governed by its own elected representatives, free from external interference. Enacted after decades of struggle, sacrifice, and negotiation, the Act remains a living testament to the Sikh community’s faith in constitutional governance and its willingness to pay the highest price for principled co-existence within a pluralistic India.

A Time for Reconciliation and Inclusivity

The Sikh faith, rooted in the enduring principles of equality, universality, and sewa (selfless service), must once again embrace its inherently inclusive ethos. At a time when Christian missionary activity is reportedly making inroads among Scheduled Caste Sikhs—many of whom are now establishing separate gurdwaras in their villages—the urgency to heal internal divisions cannot be overstated. An early and affirmative ruling by the High Court will not only reaffirm constitutional values but also lay the foundation for a more representative and legitimate SGPC. A newly elected General House—one that includes the voices and votes of Sehajdhari Sikhs—can take decisions that are fair, just, and rooted in the collective conscience of the Panth. Without such reform, calls for the much-invoked but elusive Panthic unity will remain empty rhetoric—fuel for fractious political discourse, and a source of incalculable damage to the Sikh community, the Sikh faith, and revered institutions such as Sri Akal Takht Sahib.

By Karan Bir Singh Sidhu

Retired IAS officer, Punjab cadre & Former Special Chief Secretary

Sehajdhari Sikhs's Voting Rights in SGPC: Punjab and Haryana High Court Issues Notice

Renewed Legal Challenge Over Sehajdhari Sikh Voting Rights

Great point there. The way you’ve put it across is notably articulate and merits contemplation at the most esteemed echelons of authority. It is imperative that the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) convenes with its foremost officeholders and engages the erudite minds of Sikh scholars to deliberate upon this matter with the gravity it demands. In my considered view, authentic Sehajdhari Sikhs—those who embody the spirit of gradual devotion—ought to be granted the privilege of voting rights, contingent upon a meticulous and thorough evaluation. This process of discernment should encompass a comprehensive examination of the claimant’s way of life, their deeply held convictions, the rituals observed in marriage and death, and other such practices that reflect their commitment, alongside the enduring traditions followed. Such rigorous scrutiny is not merely prudent but essential, serving as a bulwark against insidious attempts to usurp control of Sikh shrines and institutions through conspiratorial machinations. These efforts, if unchecked, could be wielded by those harboring a deliberate agenda to erode the distinct Sikh identity, undermine the sanctity of the Sikh way of life, and weaken the very school of thought that has long defined Sikhs.

ਕੇਸ ਸਿਰਫ ਸਾਡੀ ਪਹਿਚਾਣ ਹੀ ਨਹੀਂ ਬਲਕਿ ਸਾਡੀ ਬੁਨਿਆਦ ਵੀ ਹੈ। ਪਹਿਲੇ ਪਾਤਿਸ਼ਾਹ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਭਾਈ ਮਰਦਾਨਾ ਜੀ ਨੂੰ ਆਪਣੇ ਨਾਲ ਚੱਲਣ ਤੋਂ ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਇਹ ਸਪਸ਼ਟ ਹੁਕਮ ਕੀਤਾ ਸੀ ਕਿ ਭਾਈ ਜੀ ਜੇ ਅਸਾਂ ਦਾ ਸਾਥੀ ਬਣਨਾ ਹੈ ਤਾਂ ਤਿੰਨ ਸਿਧਾਂਤਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਆਪਣੀ ਜ਼ਿੰਦਗੀ ਦਾ ਅਨਿੱਖੜਵਾਂ ਅੰਗ ਬਣਾਉਣਾ ਹੋਵੇਗਾ।

1 ਕੇਸਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਅਕਾਲ ਪੁਰਖ ਦੀ ਦਾਤ ਸਮਝਦੇ ਹੋਏ ਇਹਨਾਂ ਦੀ।

ਅਸਲ ਸਰੂਪ ਵਿੱਚ ਸੰਭਾਲ ਕਰਨੀ

ਭਾਵ ਕਿ ਕੱਟਣੇ,ਰੰਗਣੇ,ਸਾੜਨੇ, ਝਾੜਨੇ ਨਹੀਂ

2 ਗੀਤ ਸਿਰਫ ਤੇ ਸਿਰਫ ਇੱਕ ਅਕਾਲ ਪੁਰਖ ਦੇ ਗਾਉਂਣੇ ਹਨ

ਭਾਵ ਕਿ ਕੀਰਤੀ ਕੇਵਲ ਪ੍ਰਮੇਸ਼ਰ ਦੀ ਕਰਨੀਂ ਹੈ। ਕਿਸੇ

ਇਨਸਾਨ ਦੀ ਸਿਫਤ ਵਿੱਚ ਕੀਰਤਨ ਨਹੀਂ ਕਰਨਾਂ

3 ਅੰਮ੍ਰਿਤ ਵੇਲੇ ਦੀ ਸੰਭਾਲ ਕਰਨੀ

ਸਪਸ਼ਟ ਹੈ ਕਿ

ਕੇਸ ਕੱਟਣ ਵਾਲਾ ਸਿੱਖ ਪਤਿਤ ਅਤੇ ਤਨਖਾਹੀਆ ਹੁੰਦਾ ਹੈ ਨਾਂ

ਕਿ ਸਹਿਜਧਾਰੀ

ਜਦੋਂ ਕੋਈ ਪ੍ਰਾਣੀ ਕਿਸੇ ਹੋਰ ਧਰਮ ਨਾਲ ਸਬੰਧਿਤ ਹੋਵੇ ਪਰੰਤੂ

ਆਸਥਾ ਦਸ ਪਾਤਸ਼ਾਹੀਆਂ ਅਤੇ ਸ੍ਰੀ ਗੁਰੂ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ ਜੀ

ਵਿੱਚ ਰੱਖਦਾ ਹੋਵੇ ਨੂੰ ਸਹਿਜਧਾਰੀ ਸਿੱਖ ਕਿਹਾ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ।

ਰਾਣੂੰ ਕਿਸੇ ਡੂੰਘੀ ਸਾਜ਼ਿਸ਼ ਅਧੀਨ ਬਹੁਤ ਦੇਰ ਤੋਂ ਸਹਿਜਧਾਰੀ

ਸਿੱਖਾਂ ਦੀ ਪਰਿਭਾਸ਼ਾ ਨੂੰ ਬਦਲਣ ਲਈ ਯਤਨਸ਼ੀਲ

ਹੈ ਜਿਸ ਦੇ ਪਿਛੋਕੜ ਨੂੰ ਪੜਚੋਲਣ ਦੀ ਜ਼ਰੂਰਤ ਹੈ ।

ਪਰ ਅਫਸੋਸ ਕਿ ਸਾਡੇ ਧਰਮ ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧਨ ਅਤੇ ਸਿੱਖ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ

ਵਿੱਚ ਇਸ ਸਮੇਂ ਸਿੱਖੀ ਸਰੂਪ ਵਿੱਚ ਵਿਚਰ ਰਹੇ ਘੁਸਪੈਠੀਏ ਸਿਰਫ ਕੁਰਸੀ ਦੀ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਖਚਿਤ ਹਨ। ਨਾਂ ਤੇ ਇਹਨਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਸਿੱਖੀ ਸਿਧਾਂਤਾਂ ਦਾ ਕੋਈ ਗਿਆਨ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਨਾਂ ਹੀ ਕੁਝ ਸਿੱਖਣਾਂ ਅਤੇ ਕਰਨਾਂ ਚਾਹੁੰਦੇ ਹਨ। ਪਰ ਯਾਦ ਰੱਖਣਾ ਹੋਵੇਗਾ ਕਿ ਜਦੋਂ ਜਦੋਂ ਵੀ ਸਿੱਖ ਆਗੂਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਅਜਿਹੀਆ ਗਿਰਾਵਟਾਂ ਵੇਖੀਆਂ ਗਈਆਂ ਕੌਮ ਨੇ ਮੋਰਚੇ ਲਾਏ ਕੇ ਕੌਮ ਨੂੰ ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਤੋਂ ਵੀ ਵੱਧ ਮਜ਼ਬੂਤ ਕੀਤਾ ਅਤੇ ਇਹ ਭਵਿੱਖ ਵਿੱਚ ਵੀ ਅਜਿਹਾ ਹੁੰਦਾ ਰਹੇਗਾ ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਇਹ ਕੌਮ ਕੌਮੀ ਪ੍ਰਵਾਨਿਆਂ, ਯੋਧਿਆਂ ਅਤੇ ਆਪਾਂ ਵਾਰ ਕੇ ਧਰਮ ਦੀ ਰੱਖਿਆ ਕਰਨੀ ਜਾਂਣਦੀ ਹੈ। ਆਪਣੇ ਪਵਿੱਤਰ ਗੁਰਧਾਮਾਂ ਦਾ ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧ ਕਿਸੇ ਪਤਿਤ ਨੂੰ ਦਿੱਤਾ ਜਾਣਾਂ ਕਦੇ ਵੀ ਕੌਮ ਪ੍ਰਵਾਨ ਨਹੀਂ ਕਰੇਗੀ।

ਸਤਿਕਾਰ ਸਹਿਤ

ਨਿਸ਼ਾਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਕਾਹਲੋਂ