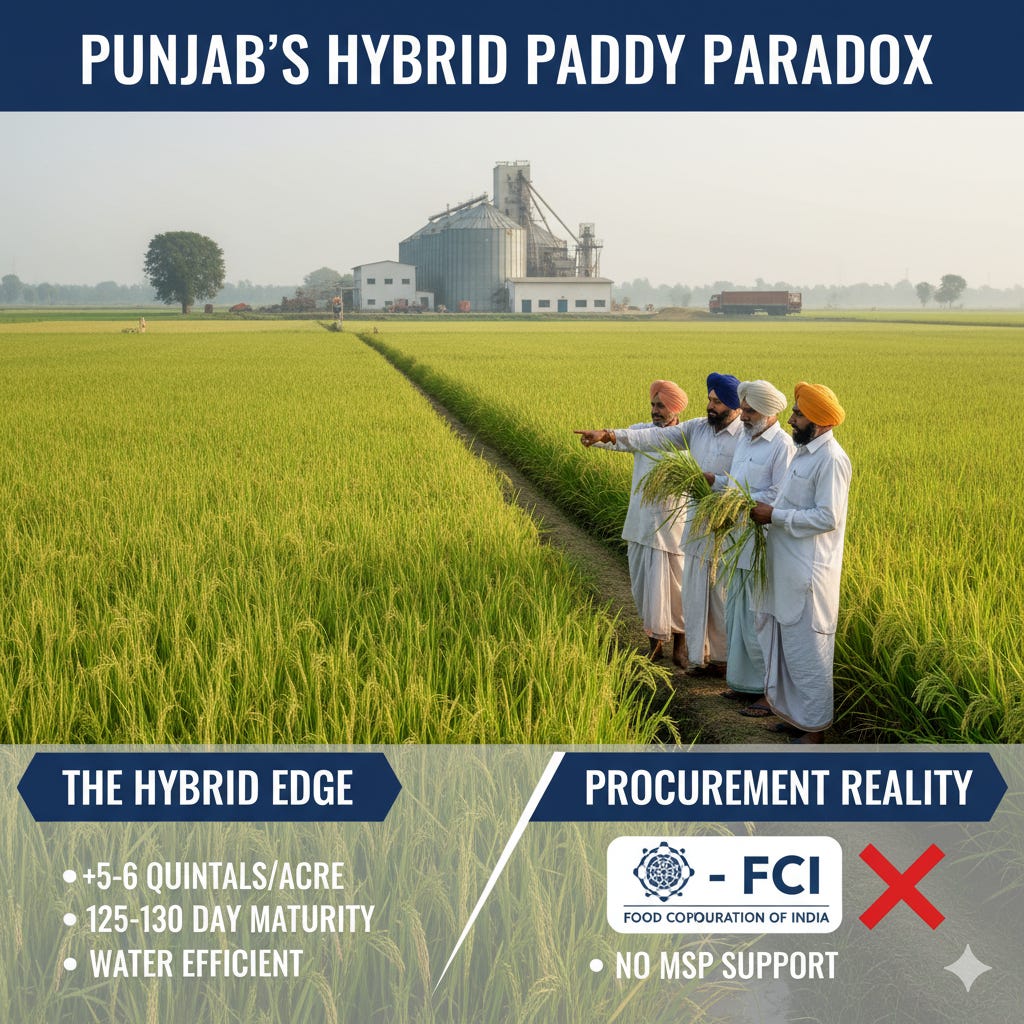

Punjab’s Hybrid Paddy Paradox: When Government Seed Approval Confronts FCI's Procurement Reality

Why farmers sow hybrid paddy in Punjab and Haryana, yet government procurement policies refuse to adapt — is the rice millers’ lobby to blame?

Karan Bir Singh Sidhu, retired IAS and former Special Chief Secretary, Punjab, examines the paradox between nationally approved hybrid paddy seeds and the FCI’s refusal to procure them—despite these varieties being economically, environmentally, and agronomically superior.

Punjab’s Hybrid Paddy Paradox

Punjab’s paddy fields this season tell a fascinating story of innovation clashing with policy paralysis. Just a year after being rejected by rice millers and banned by the State Government, hybrid paddy seeds are back in the fields — now legally validated by the courts and grudgingly accepted by private millers out of economic necessity. Yet, despite their proven yields and central certification, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) still refuses to procure them, revealing the enduring contradictions in India’s agricultural governance.

The Hybrid Edge: Yield, Speed, and Resilience

Hybrid paddy varieties have long appealed to Punjabi farmers because of their superior productivity and adaptability. On average, hybrids produce 5 to 6 quintals more per acre than traditional high-yielding types, reaching up to 35–40 quintals under favorable conditions. This results in additional earnings of ₹13,000–₹14,000 per acre — a vital boost at a time when farm profitability is shrinking.

Hybrids also mature faster — within 125–130 days, nearly three weeks earlier than conventional varieties like PR-126 or Pusa-44. Earlier maturity means lower water consumption, faster field turnover for wheat sowing, and fewer stubble-related issues contributing to air pollution. Their deeper root systems and better stress tolerance also make hybrids well-suited for challenging conditions such as heat stress, intermittent flooding, or saline soils common in regions like Fazilka, Muktsar, and Mansa.

Despite slightly higher seed prices (₹550–₹650 per kg versus ₹250–₹400 for conventional varieties), farmers view hybrids as an investment rather than a cost — the higher yields, time savings, and water efficiency more than make up the difference. Hybrid paddy, in essence, aligns with Punjab’s shifting environmental reality, where groundwater is depleting and weather patterns have become increasingly erratic.

Certified by Science and Law

Hybrid paddy seeds are not experimental— they are officially approved by the Government of India and scientifically validated through years of testing. Under the All India Coordinated Rice Improvement Project (AICRIP) led by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), every hybrid variety is field-tested for three years across multiple agro-climatic zones before being notified under the Seeds Act, 1966 by the Ministry of Agriculture.

Once notified, a seed variety gains nationwide validity, meaning no state government can prohibit its sale or use. These varieties meet all national milling and grain-quality standards: ICAR and Punjab Agricultural University (PAU) trials show that hybrids often achieve 70–72.5% total milling recovery and 60–62% head rice yield, comfortably meeting FCI’s 67 percent out-turn ratio (OTR) requirement.

The Federation of Seed Industry of India has repeatedly emphasized that these hybrids meet every parameter required under national standards. Under the Seed Control Order of 1983, states can monitor seed quality but cannot ban centrally notified varieties. Nonetheless, in April 2025, the Punjab government prohibited all hybrid seeds — a decision that was swiftly overturned by the judiciary.

The High Court Steps In

On 19 August 2025, the Punjab and Haryana High Court struck down the Punjab government’s blanket ban on hybrid paddy seeds issued that April. In a landmark ruling, Justice Kuldeep Tiwari clarified that states cannot prohibit “notified” hybrid varieties listed under the central Seeds Act, 1966. The court restored farmers’ and seed companies’ legal right to use and sell such hybrids across Punjab.

Importantly, the ruling upheld the earlier 2019 bar only on non-notified hybrid seeds, maintaining that seeds not cleared by central authorities could still be restricted for quality reasons. The judgment distinguished between legally notified hybrids — those rigorously tested and approved by national institutions — and unregulated or locally developed hybrids lacking statutory clearance.

This judicial intervention provided much-needed legal certainty, effectively reframing the debate. The hybrid controversy was no longer about legality of cultivation, but about the more practical challenges of milling yields, recovery ratios, and market acceptance. The courts, in essence, cleared the way for hybrid adoption while leaving economic and technical adaptation to the market players.

Last Year’s Rejection: The Milling Backlash

The fiercest opposition to hybrid paddy last year came not from regulators but from the rice millers. Their objection centered on the out-turn ratio (OTR) — the percentage of rice recovered after milling. Under FCI norms, millers must yield at least 67 percent rice per 100 kg of paddy. Millers claimed hybrids fell short, producing only 60–63 percent OTR with excessive breakage that left them unable to meet delivery contracts to FCI without losing money.

Facing heavy losses, Punjab’s millers collectively refused to accept hybrid paddy in 2024. This led to administrative disarray and prompted the state to impose its now-overturned ban. From the millers’ perspective, FCI procurement rules were non-negotiable; any grain with lower recovery meant extra costs, as they would need to purchase additional rice to fulfill quota obligations.

However, according to PAU agronomists and seed industry experts, most of the OTR shortfall stemmed from inadequate post-harvest handling — premature harvesting, improper drying, and the use of outdated milling machinery. Hybrid grains, they note, often have slightly different composition and moisture dynamics that require adjusted milling settings — something many millers have been reluctant to adopt.

This Year’s Reversal: Economic Necessity

The 2025 season forced a re-evaluation. Devastating rainfall and heat fluctuations slashed yields for conventional paddy. In many areas, output dropped to 22–23 quintals per acre instead of the usual 28–30. Some flood-affected districts recorded as little as 5 quintals per two acres.

Confronted with severe paddy shortages, millers turned to hybrid stocks to keep their facilities operational. This season, they privately procured about 1.5–2 lakh metric tonnes of hybrid paddy, paying farmers between ₹1,800–₹2,000 per quintal. Although this represents only about 1 percent of Punjab’s overall paddy output, it reflects a pragmatic shift — millers are learning that even with perceived milling losses, limited hybrid procurement is preferable to idle mills.

Why FCI Still Excludes Hybrids

Despite national certification, FCI does not procure hybrid paddy. The reasons are bureaucratic rather than scientific. FCI procurement operations adhere rigidly to Fair Average Quality (FAQ) norms, which currently recognize only “common” and “Grade A” varieties historically used across states. Hybrids, though valid under the Seeds Act, are missing from this procurement glossary and thus remain outside the MSP mechanism.

The Ministry of Food and Public Distribution, which oversees FCI, has argued that procurement standards must remain uniform nationwide to avoid administrative complexity. It has commissioned studies (including one by IIT Kharagpur) to assess hybrid milling performance but has yet to release findings or amend policy. This leaves hybrid farmers excluded from MSP assurance — a contradiction given the government’s parallel promotion of hybrid rice under national agricultural programs.

The Machinery Gap: Stuck in the Past

Another barrier lies inside the mills themselves. Many rice mills in Punjab and Haryana are decades old, designed for processing traditional long-grain varieties under predictably stable milling conditions. Upgrading equipment to handle hybrids — which have denser grain structures and moisture-sensitive husks — requires multimillion-rupee investments.

Millers operating under tight profit margins and government-controlled pricing see little incentive to modernize without policy clarity. Most rely on Cash Credit Limits (CCL) from state banks tied to government procurement contracts, not private trade. Since hybrids are outside FCI operations, mills processing them must self-finance, raising financial risks. As a result, the milling infrastructure has not evolved to accommodate hybrids, even when research institutions confirm that modern machines can easily meet FCI’s 67 percent OTR requirement for these varieties.

What Punjab Agricultural University Found

Punjab Agricultural University’s tests and multi-location trials have shown that hybrid varieties — when harvested at the proper maturity and milled under appropriate drying and pressure conditions — meet or exceed the standard OTR required by FCI. The university attributes reported milling inefficiencies mainly to suboptimal field and post-harvest management rather than genetic flaws in the hybrids.

PAU researchers further note that problems reported by some millers likely resulted from seed contamination. Unscrupulous local sellers allegedly mixed unregistered or non-notified hybrids with certified stock, undermining both performance and perception. PAU emphasized that it had not released any hybrid version of popular local cultivars like PR-126 and that properly notified hybrids perform consistently with approved benchmarks.

A System Working in Silos

The hybrid paddy debate exposes a broader policy failure — India’s agricultural system operating in silos. On one side, the Ministry of Agriculture and ICAR promote hybrid rice as essential to enhancing yields, conserving water, and increasing farmer income. On the other, the Ministry of Food and Public Distribution refuses to align procurement policy with these scientific advancements, keeping hybrids outside MSP coverage.

This institutional disconnect undermines the very innovation the government funds and encourages. Farmers adopting hybrids face market uncertainty; millers hesitate to modernize; and FCI, the central procurement arm, continues to base decisions on outdated assumptions. The result is a policy triangle where science, economics, and administration point in different directions.

Conclusion: A Pattern of Confusion and Contradictions

Punjab’s hybrid paddy episode embodies a recurring theme in India’s agricultural administration — progress throttled by fragmentation. Despite higher yields, water efficiency, and scientific approval, hybrids remain marginal in procurement. Even after judicial clarity confirming their legality, farmers still depend on private millers operating outside the government system, while outdated procurement definitions and rigid norms block mainstream adoption.

What remains quite surprising is the reticence of the Punjab Government, which consistently champions farmers’ rights and welfare, has not yet forcefully taken up this issue with the Union Government—even in a year when paddy farmers have suffered devastating flood losses. Unless the FCI updates its procurement norms and state rice mills modernize their ageing infrastructure, hybrid paddy will remain trapped in a paradox: endorsed by one ministry, obstructed by another, and only partially accepted by the marketplace.

The Punjab and Haryana High Court ruling may have settled the legal question of whether hybrids can be sown or sold, but it has not resolved the operational impasse. The real challenge now is to align government practice with government science — bridging the gap between legal clarity and systemic inertia, while keeping farmers’ welfare at the centre.

Double Whammy for Punjab Farmers: Unsold Paddy and DAP Fertilizer Shortage

Double Whammy for Punjab Farmers