Plotted Queen Elizabeth II's Assassination with a Crossbow: "To Avenge Jallianwala Bagh Massacre"

21-year-old British Sikh influenced by AI chatbot plotted to assassinate the British Monarch with a crossbow over Jallianwala Bagh massacre—sentenced to nine years by a London court.

Jallianwala's Shadows and the Perils of AI

On Christmas Day 2021, the UK was jolted by a startling act. Jaswant Singh Chail, a 21-year-old UK-born Sikh, swayed by an AI chatbot, entered Windsor Castle brandishing a crossbow. His bold intent: to assassinate Queen Elizabeth II as retribution for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Royal protection officers promptly apprehended him. While this incident underscores the lingering pain from historic tragedies like Jallianwala Bagh, it also highlights the unforeseen hazards and perils associated with the use of modern AI technology.

Inspired by Shaheed Udham Singh?

Last week, in a consequential ruling, a London court sentenced Jaswant Singh Chail to nine years in prison for his brazen act committed on the Christmas Day. While the circumstances of his arrest were already incriminating, the case was further solidified when the prosecution presented transcripts of Chail's deep interactions with a feminine AI bot, "Sarai". These exchanges not only established the unsettling sway the AI had over him but also revealed the depth of his motivations. Upon assessing his mental state, the judge branded Chail as a troubled Star Wars fanatic who frequently identified himself as "Darth Chailus" and decreed that he undergo psychiatric evaluation and treatment before beginning his prison term.

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre: “The Butcher of Amritsar”

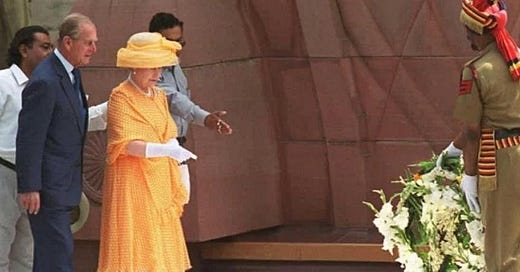

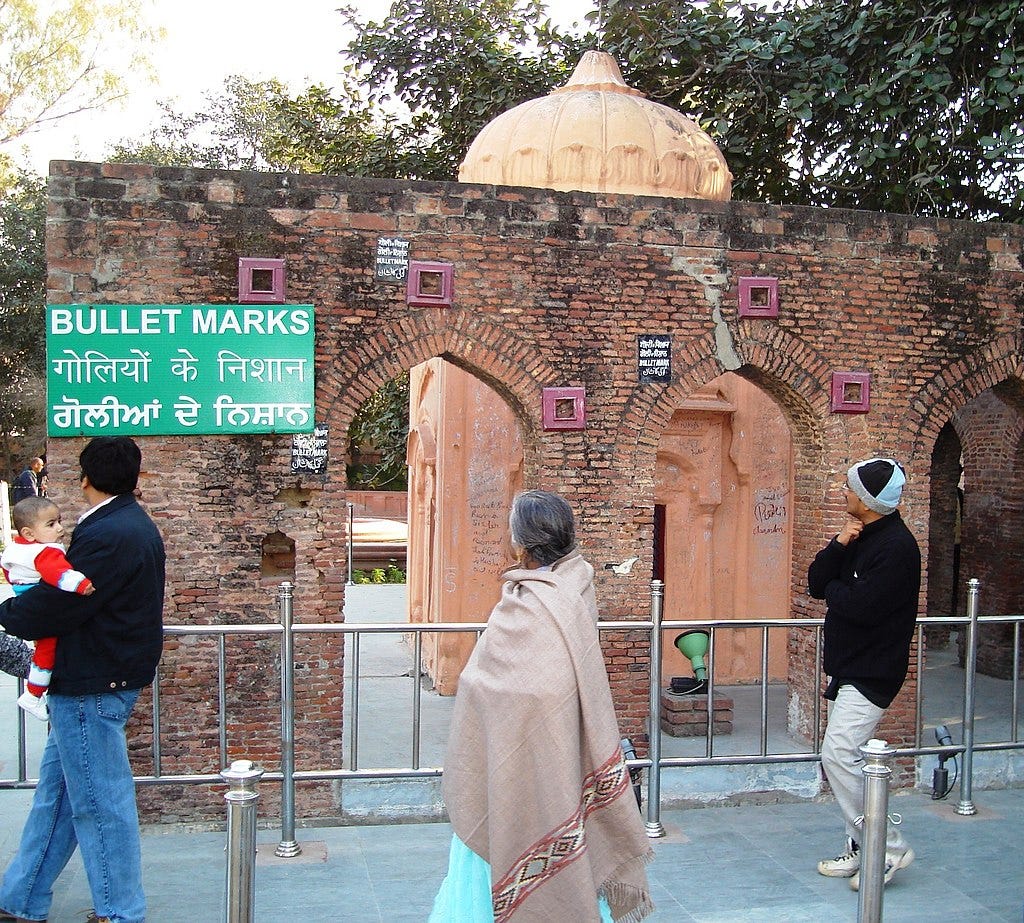

The shadow of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre on 13 April 1919 still looms large, influencing individuals like Chail even today. Orchestrated by Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, infamously dubbed “the Butcher of Amritsar”, this harrowing incident saw troops ruthlessly firing upon a peaceful gathering, killing at least 379 and injuring over a thousand. Dyer's role in this dark epoch of India's colonial past led him to live out his life in relative obscurity until his death in Somerset in 1927, at the age of 62. Significantly, while Queen Elizabeth II and various British Prime Ministers have acknowledged the tragedy, expressing deep regret and paying homage to the martyrs of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, an official apology continues to be elusive, casting a persistent shadow over the chronicles of British-Indian relations.

The Young Udham Singh

Udham Singh, born on 26 December 1899 into a Kamboj Sikh family in Sunam, Punjab, was nurtured by the Chief Khalsa Diwan Orphanage in Amritsar. Showing early patriotic fervour, he persuaded the authorities to let him serve in the British Indian Army during World War I. Despite initial service with the 32nd Sikh Pioneers on rail restoration projects up to Basra, his youth and disputes with superiors brought him back to Punjab. Resolute, he re-enlisted in 1918, contributing his carpentry and machinery maintenance skills in Basra and Baghdad. By early 1919, destiny led him back to Amritsar, where, at the age of 19, he was serving water to Baisakhi festival-goers at Jallianwala Bagh. Bearing witness to the harrowing massacre profoundly impacted his psyche, sowing seeds of revenge that would determine his future path.

Assassination of Michael O'Dwyer: Shaheed Udham Singh and his Legacy

The haunting legacy of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre saw one of its most dramatic chapters unfold when Michael O'Dwyer, the Governor of Punjab at the time of the massacre, was assassinated. On 13 March 1940, at the age of 75, O'Dwyer was targeted at Caxton Hall, Westminster, London by Udham Singh, an Indian revolutionary. Singh had harboured his vengeful intent for 21 long years before fulfilling his life’s mission, emblematic of the profound scars the Amritsar tragedy had etched on the Indian psyche.

At his trial, Singh did not deny his actions. Asserting that O'Dwyer deserved his fate, he proclaimed he acted for his country and expressed no fear of death. Unwavering in his convictions, Singh did not seek clemency, further showcasing his indomitable spirit. British justice, however, was swift and unyielding; he was executed on 31 July 1940 in England. Yet, his martyrdom ignited a spark. Later in 1974, in a tribute to his enduring legacy, his remains were exhumed and returned to India, and received by Prime Minister Mrs Indira Gandhi and President Giani Zail Singh. Cremated in his hometown, Sunam, with full state honours, Singh's memory continues to inspire and resonate with generations.

AI-Questions of Ethics and Perils

Amidst these historical burdens, the rise of AI technology adds a novel layer of challenges. While AI has immense potential, it can, at times, intensify dangerous emotions and intentions. Chail's alarming bond with "Sarai", his chatbot from the Replika app, is a glaring example of how unchecked AI interactions can go awry, especially when devoid of human monitoring and discernment.

As we steer into the future, we are presented with dual challenges: reconciling with our profound historical wounds and ensuring that the march of AI is responsible and ethically grounded. Both trajectories demand vigilance, public awareness, and robust safeguarding mechanisms within AI platforms.

Looking ahead, in India and Abroad

For the Indian diaspora, especially in the UK, this unsettling event serves as a poignant reminder. It underscores the importance of understanding our rich history while also being cautious and discerning in an AI-dominated era.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, an indelible blot on our historical canvas, will forever remind us of the past's scars. As we tread forward, our embrace of technology must be anchored in ethics, responsibility, and an unwavering commitment to the greater good of humanity.

EPILOGUE

During my tenure from 1990 to 1996, I had the profound honour of serving in Amritsar, taking on the mantle of Deputy Commissioner in the latter four years and fulfilling the role of second in command for the initial two. Throughout this period, it became a deeply personal mission for me to pay respects to the martyrs of Jallianwala Bagh every 13th of April. This included a particularly poignant moment in 1994 which marked the 75th anniversary of that fateful event.

Our training as civil servants equips us to remain composed, even in tumultuous situations, and my personal upbringing too reinforced this stoic discipline. However, I must candidly confess that during those years, especially as a young man in my late 20s and early 30s, the profound sorrow and solemnity of the Jallianwala tragedy were occasionally interspersed with an underlying sentiment of retribution