Pakeezah of Sher-e-Punjab: The Untold Chronicle of Moran Sarkar and Maharaja Ranjit Singh

The tale of Moran Sarkar and Maharaja Ranjit Singh defies easy moral judgments. Was she an opportunist or a remarkable woman of substance? A courtesan or a queen?

About the Author:

Karan Bir Singh Sidhu, IAS (Retd.), is a former Special Chief Secretary, Government of Punjab, and a senior officer of the Punjab cadre. A keen student of Sikh history and cultural narratives, he is committed to presenting historically grounded yet sensitively written accounts that aim to correct distortions and foster greater understanding. His work often focuses on themes of religious harmony, pluralism, and the unifying forces that have shaped Punjab’s rich heritage.

Origins of an Enchantress

Moran Sarkar (c. 1781–1862), a name that still evokes intrigue, was born into a Barakzai Pashtun Muslim family in the small village of Makhan Windi near Amritsar. Some later accounts suggest Kashmiri origins. Before fate intervened, Moran earned her living as a nautch girl—a dancer skilled in the art of music and movement, performing for nobility and merchants alike. It was a profession held in low social regard, but one that paradoxically afforded access to royal circles.

A Fateful Encounter

It was during one such performance—either at the Baradari of Dhanoa Kalan or amid the exuberant Basant festivities in Lahore’s Shalimar Gardens—that young Maharaja Ranjit Singh, already the ruler of Lahore at just 21, first saw Moran. Her graceful dance, compared to the elegance of a peacock, captivated him. The ruler, known for his valour and equally for his affections, bestowed upon her the title “Moran” — meaning “peacock.”

The Controversial Marriage

In 1802, the sovereign of the Sikh Empire married Moran. Some sources claim a nikah was performed; others simply note a grand ceremonial procession. The Sikh ruler never required Moran to renounce her faith—a remarkable gesture of tolerance. The wedding, funded by the wealthy nobleman Samad Joo Kashmiri, took place at his haveli in Amritsar, amid much fanfare.

For all its romanticism, the marriage shocked the orthodox Sikh clergy. How could Sher-e-Punjab, the Lion of Punjab, wed a Muslim dancer?

Summons from the Akal Takht

The Akal Takht, the supreme seat of Sikh temporal authority, swiftly summoned Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Declared Tankhaiyya—guilty of religious misconduct—he was sentenced to be flogged 100 lashes by none other than Akali Phula Singh, the formidable Jathedar.

The episode that followed remains etched in Sikh lore. The powerful king arrived humbly, bared his back before the sacred assembly, prepared to accept the sentence. Moved by his humility and sincerity, Akali Phula Singh sought the congregation’s counsel—should the Maharaja not be forgiven? A single symbolic lash was ultimately administered, reaffirming the supremacy of Sikh religious authority, and the Maharaja’s enduring respect for it.

Pul Moran—A Bridge of Love

Near today’s Indo-Pak border, in a modest village called Pul Kanjri, stands a simple bridge—once Pul Moran. Legend recounts that when Moran lost her silver slipper while crossing a canal en route to a performance, she refused to dance again until a proper bridge was built. The smitten Maharaja ordered its construction without delay. Though later renamed with a derogatory tone (kanjri meaning courtesan), the structure still stands—a Punjabi Taj Mahal of sorts.

A Palace of Her Own

Following their union, Ranjit Singh gifted Moran a grand haveli within Lahore’s Papar Mandi, near Shah Almi Gate. Here, Moran established her own court, where she heard public petitions and advised the Maharaja. Locals began to refer to her with affection and respect as Moran Sarkar.

An Enigmatic Legacy—Children and Coins

Historical records are silent on whether Moran bore the Maharaja any children. Yet, her influence was evident. Between 1802 and 1827, coins known as Moranshahi—adorned with a peacock feather—were issued from the royal mint. This bold tribute to a former nautch girl scandalised religious orthodoxy. Under pressure, the Maharaja withdrew the coins, relocating minting back to Amritsar.

Philanthropy and Religious Harmony

Moran’s contributions extended beyond courtly charms. At her behest, in 1824, Ranjit Singh commissioned the construction of Masjid-e-Tawaifan in Lahore—a rare mosque built at the request of a Sikh ruler’s Muslim consort. Now called Mai Moran Masjid, it stands today as a testament to religious harmony. She also funded a madrasa, the Shivala temple in Lahore Fort, and Persian and Punjabi language schools.

Later Years—A Life in Shadows

Accounts diverge on Moran’s later life. Some say she fell from favour and was sent to Pathankot in 1811. Others cite her continued influence, evidenced by the mosque’s construction a decade later. After Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839, Moran lived quietly in Lahore on a British pension, outliving the Maharaja by 23 years. She passed away in 1862. Her grave, said to lie near Miani Sahib Graveyard, remains unverified.

Reassessing the Pakeezah of Punjab

The tale of Moran Sarkar and Maharaja Ranjit Singh defies easy moral judgments. Was she an opportunist or a remarkable woman of substance? A courtesan or a queen? In Pakistan, Mai Moran is revered for her charity and wisdom. In Indian Punjab, orthodoxy still casts her in a controversial light.

Yet her story illuminates an age of unexpected tolerance and cultural fluidity. The Lion of Punjab, though chastened by the Akal Takht, never disowned his affection for the dancer who became a queen. Their legend—part love story, part political scandal—continues to evoke fascination.

Even today, Moran Sarkar’s life forces us to re-examine questions of love, faith, class, and power in the richly textured history of Punjab.

Post-script: The Maharaja’s Many Queens and Heirs

The story of Moran Sarkar is but one fascinating thread in the vast and colourful tapestry of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s life. The Sher-e-Punjab was no ascetic—he married no fewer than twenty wives by formal ceremony (Sikh, Hindu, and Muslim), and maintained a harem that court chroniclers claim swelled at times to forty-six women.

His first marriage, a political alliance with Maharani Mehtab Kaur of the Kanhaiya Misl, was fraught with tension. It was his union with Maharani Datar Kaur (Mai Nakain) that brought the Maharaja both personal happiness and a strong queenly partner in governance. Of his wives, Moran stands apart—not by royal lineage or political stature, but by sheer personal magnetism and the controversy she stirred.

In total, Ranjit Singh fathered eight sons, though, according to some accounts, he formally acknowledged only Kharak Singh (by Datar Kaur) and Duleep Singh (by Maharani Jind Kaur, his last wife) as his biological heirs. His children—some born of queens, others of lesser wives—would go on to inherit a fractious and declining empire after his death in 1839.

In this crowded royal landscape, Moran’s place is singular. Neither empress nor mother of a future king, she remains remembered not for dynastic influence but for her bold defiance of social taboos, her charitable works, and her hold over the Lion of Punjab’s heart. Her legend lingers—bridging the realms of history and folklore—as the Pakeezah of Sher-e-Punjab.

Princess Bamba Duleep Singh— the enigmatic heiress.

Princess Bamba Duleep Singh: The Last Torchbearer of the Legacy of “Sher-e-Punjab”.

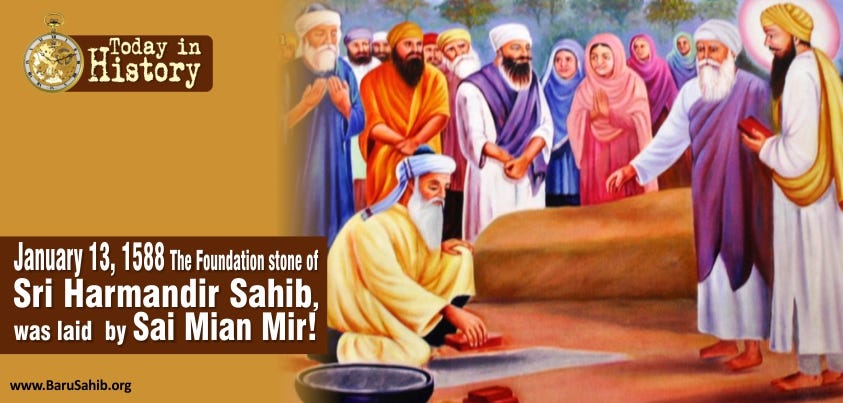

Beyond Divisions: Chronicling Sikh-Muslim Instances of Amity in History

Introduction— history of hostilities: Throughout history, narratives have perpetuated the notion of animosity between Sikhs and Muslims. Tragic events, especially the martyrdom of the two Sikh Gurus, Guru Arjan Dev Ji and Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, and the unparalleled sacrifice of the four "