India's Citizenship Act: Lessons from Israel

"Comparing the Citizenship Amendment Act: Drawing Lessons from Israel's Immigration Policy for Jews"

In today's world, the intersection of immigration, citizenship, and religious identity has become a topic of intense scrutiny and debate. The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA) in India, with its seemingly exclusionary provisions and the ensuing controversy it sparked, provides a unique opportunity for us to examine the complexities surrounding these issues. As we delve into the CAA and its implications, it is worth exploring the case of Israel—a nation officially designated as secular, yet renowned for its fast-track immigration process and preferential treatment of Jews from around the globe. By examining the Israeli experience, we can gain valuable insights into the delicate balance between religious identity, statehood, and the treatment of minority communities, in a historical context.

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) is a piece of legislation passed by the Indian Parliament in December 2019. The Act amends the Citizenship Act of 1955 and introduces changes to the process of acquiring Indian citizenship.

The key provisions of the Citizenship Amendment Act are as follows:

Granting of Citizenship: The CAA grants citizenship to non-Muslim migrants from three neighboring countries—Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan—who entered India on or before December 31, 2014. It applies to Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians.

Exemption for Muslims: The Act does not include Muslims from these three countries as eligible for fast-tracked citizenship, which has led to criticism and accusations of religious discrimination.

The controversy surrounding the Citizenship Amendment Act primarily stems from concerns related to its implications for India's secular principles, constitutional guarantees of equality, and the treatment of religious minorities. Critics argue that the exclusion of Muslims from the CAA violates the principle of equality enshrined in the Indian Constitution, which prohibits discrimination on the grounds of religion. They view the Act as discriminatory and argue that it undermines the secular fabric of the country.

Nehru-Liaqat Pact: In examining the historical context of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in India, it is essential to delve into the Nehru-Liaqat Pact of 1950, as it provides a crucial backdrop to the necessity of the CAA. The Nehru-Liaqat Pact, signed on April 8, 1950, between India's Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan's Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, aimed to address the protection of religious minorities in the aftermath of the Partition of India in 1947.

The Nehru-Liaqat Pact was a significant diplomatic agreement that sought to ensure the welfare and security of minority communities in both India and Pakistan. It outlined various commitments, including the protection of minority rights, non-discrimination based on religion, and the prevention of forced conversions. The pact was intended to be a foundation for fostering harmonious coexistence between religious communities. Its key features include:

refugees were allowed to return unmolested to dispose of their property.

abducted women and looted property were to be returned.

forced conversions were unrecognized.

minority rights, as equal citizens, were confirmed or reaffirmed by both the countries.

However, over the years, it became evident that Pakistan had failed to fulfill its obligations under the Nehru-Liaqat Pact, particularly in safeguarding the rights of its minority communities. Reports of discrimination, persecution, and violence against religious minorities in Pakistan persisted, leading to an unfinished agenda in fulfilling the commitments made in the pact.

It is in this context that the CAA emerges as India’s response to address not merely the shortcomings of the Nehru-Liaqat Pact, as Pakistan's failure to protect its minority communities, but also as a compelling need for India to take proactive measures, in view of the extant geo-political realities not only in Pakistan but also in the wake of the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan. By offering a fast-track citizenship path to Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, and Christians from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh, the CAA aims to provide refuge and protection to those who have been subjected to persecution and discrimination in their home countries.

Viewed from this perspective, the CAA can be seen as serving as a means to rectify the gaps in the implementation of the Nehru-Liaqat Pact and uphold the principles of equality and justice for religious minorities. While it has generated debates and discussions, it is crucial to recognize the historical impetus behind its enactment and the pressing need to address the challenges faced by minority communities in neighboring countries.

By acknowledging the historical context of the Nehru-Liaqat Pact (signed in 1950) and the shortcomings in its implementation, and the ensuing necessity of the CAA, a comprehensive understanding of India's approach towards protecting and providing refuge to persecuted religious minorities can be developed.

No doubt, he CAA initially sparked widespread protests across India, with critics voicing their concerns about religious discrimination and the erosion of India's secular principles, but things have since settled own without much damage to life and property. Supporters of the Act argue that, keeping in view the historical context of India and its neighbouring nations since 1947, it is a necessary measure to protect religious minorities facing persecution in their respective countries, without in any way discriminating against its own Muslim citizens.

Birth of Israel: After World War II, the establishment of the State of Israel came as a result of various historical and political factors. Here's a brief overview:

1. Zionist Movement: The Zionist movement, which advocated for the establishment of a Jewish homeland, gained momentum in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Jewish communities worldwide supported the idea of creating a Jewish state in Palestine, which was under British control at the time.

2. Balfour Declaration (1917): The British government issued the Balfour Declaration, expressing support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine. This declaration provided political momentum for Jewish settlement and immigration.

3. British Mandate (1920-1948): After World War I, the League of Nations granted Britain a mandate to administer Palestine. During this period, Jewish immigration increased, and Jewish institutions, infrastructure, and settlements developed. However, tensions between Jewish and Arab communities escalated.

4. Holocaust and Jewish Displacement: The horrors of the Holocaust during World War II, in which millions of Jews were systematically persecuted and killed by Nazi Germany, highlighted the urgency of finding a safe haven for Jewish survivors and displaced persons.

5. United Nations Partition Plan (1947): The United Nations proposed a partition plan for Palestine, suggesting the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states with an internationally administered Jerusalem. The plan was accepted by Jewish leaders but rejected by Arab states and Palestinian Arab leaders.

6. Israeli Declaration of Independence (1948): On May 14, 1948, the British mandate expired, and David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, declared the establishment of the State of Israel. The declaration asserted Israel's independence, outlined democratic principles, and extended an invitation to Arab residents to participate in the country's development. Arab states, however, rejected the declaration and initiated military interventions.

7. Arab-Israeli War (1948-1949): Following the declaration, neighboring Arab states, including Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, attacked Israel. The war resulted in an armistice agreement, with Israel gaining control over more territory than initially outlined in the partition plan.

It's important to note that the creation of Israel has been a source of both celebration for Jewish communities and a point of contention with Palestinian and Arab communities, leading to ongoing conflicts and challenges in the region. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains a significant issue in the Middle East.

Is Israel a Jewish State or a Secular State? The nature of Israel's identity and character is a complex and debated topic. Israel describes itself as both a Jewish and democratic state. This duality reflects the aspirations to maintain a Jewish national homeland while upholding democratic values and protecting the rights of all its citizens. Israel has a predominantly Jewish population, and Jewish heritage, culture, and religion have played significant roles in shaping the country. The Israeli flag, national anthem, and some aspects of the legal system reflect Jewish symbolism and traditions.

However, Israel also guarantees freedom of religion and conscience to its citizens through its Basic Laws. It recognizes and protects the rights of religious minorities, including Christians, Muslims, Druze, and others. Israel has non-Jewish citizens who practice various religions, and they have the right to worship, establish religious institutions, and participate in public life. Approximately 17.7% of the population of Israel consists of Muslim citizens. The Muslim population in Israel includes various ethnic and linguistic groups, such as Arab Muslims, Bedouin Muslims, and Druze Muslims. Arab Muslims constitute the largest portion of the Muslim population in Israel.

Separation of Religion and State? While Israel does not have a formal separation of religion and state, there are ongoing discussions and debates within Israeli society regarding the appropriate balance between Jewish identity and democratic principles. Some advocate for a more secular approach, while others argue for maintaining a strong Jewish character. In summary, Israel can be characterized as a Jewish state due to its historical and cultural ties to Judaism, but it also strives to uphold democratic principles and provide equal rights to all its citizens, regardless of their religious affiliation.

However, it’s important to underscore that in Israel, all citizens, regardless of their religious affiliation, are entitled to the same legal rights and protections under the law. The Basic Laws of Israel guarantee equal rights and prohibit discrimination based on religion, race, or ethnicity.

However, it is worth mentioning that there are certain aspects of Israeli law that differentiate between Jewish and non-Jewish citizens. For instance, matters of personal status, such as marriage and divorce, for Jewish citizens are governed by Jewish religious law (Halakha) and administered by religious courts. Non-Jewish citizens, including Muslim citizens, have their personal status matters handled by their respective religious courts, such as Islamic courts for Muslims.

There have been ongoing discussions and debates within Israeli society about the need to promote full equality for all citizens, regardless of religious or ethnic background, and to address any perceived inequalities that may exist. The topic of equality and the rights of various communities in Israel is an evolving and sometimes contentious issue that is subject to ongoing debate and discussion.

A Written Constitution? No, Israel does not have a formal written constitution. Instead, it has what is called "Basic Laws" that serve as constitutional principles and form the legal foundation of the country. These Basic Laws cover various aspects of governance, human rights, and the relationship between the state and its citizens.

While Israel does not have a constitution that explicitly declares the country as secular, it does provide for freedom of religion and conscience in its Basic Laws. The Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty protects the rights of individuals to practice their religion or hold no religious belief, and the Basic Law: Freedom of Occupation guarantees freedom of employment and access to public office regardless of religion.

However, it is important to note that Israel has a unique relationship between religion and state. Jewish religious law, known as Halakha, has some influence over certain aspects of personal status law, such as marriage and divorce, which are administered by religious courts. This arrangement reflects Israel's historical and cultural ties to Judaism as a predominantly Jewish state.

Preference to Jews in Immigration? Yes, under the Law of Return, which was passed in 1950, Jews have the right to immigrate to Israel and gain Israeli citizenship more easily than non-Jews. The Law of Return states that every Jew has the right to come to Israel as an oleh (immigrant) and become an Israeli citizen. This preferential treatment for Jewish immigrants is based on the historical context of Israel as a haven for Jews and the desire to provide a safe haven for Jews around the world. It reflects the notion of Israel as a Jewish homeland.

Non-Jews who wish to immigrate to Israel can do so through other avenues, such as family reunification, work permits, or seeking asylum. However, the process for non-Jewish immigrants is generally more complex and may involve meeting specific criteria and going through a longer naturalization process.

It's important to note that while the Law of Return gives preference to Jewish immigrants, it does not mean that Jews are the only individuals who can become Israeli citizens. Non-Jews who meet the legal requirements can also acquire Israeli citizenship through naturalization processes. The Israeli government has implemented policies to facilitate the naturalization process for non-Jews, but it generally remains more streamlined for Jewish immigrants.

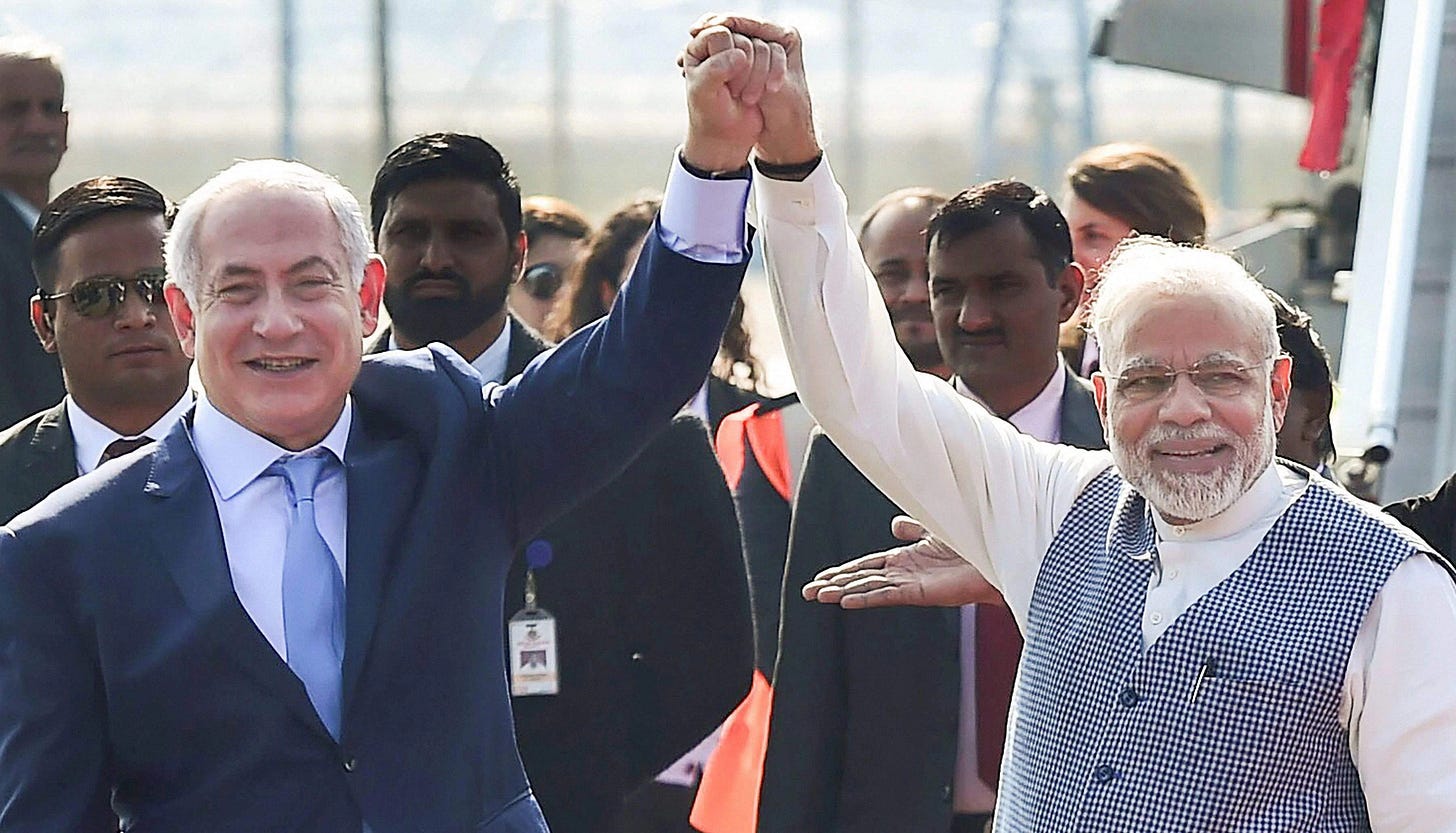

Comparative Analysis: In analysing the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in India and its implications, it is crucial to consider the broader global context and draw insights from the experiences of other nations. Israel, often hailed as a secular state, offers a relevant case study with its fast-track immigration process and preferential treatment of Jews worldwide. By examining this parallel, we can steer along a path towards a comprehensive and wholistic understanding and appreciation of India's approach.

The historical context plays a significant role in comprehending the fast-track citizenship provisions for Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis and Buddhists from the neighboring countries. The partition riots of 1947 resulted in immense human suffering and mass displacement. Acknowledging this historical backdrop reminds us of the immense importance of providing a safe haven and a permanent home for those who have, in the decades after our Independence, faced persecution in the counties of their citizenship, owing to changed and evolving circumstances therein.

Israel's policy of fast-track immigration for Jews, despite being designated a secular state, offers a very pertinent lesson. It highlights the recognition of historical ties, cultural affinity, and the need to protect and accommodate minority communities who face persecution in their countries of origin. This approach aligns with India's aim to safeguard the interests of religious minorities and provide them with a secure environment.

Critics may argue that these policies violate the secular principles enshrined in the Indian Constitution. However, it is important to emphasize that providing refuge and expedited citizenship to specific religious communities does not undermine the secular nature of the state. It is a targeted response aimed at addressing the unique challenges faced by these communities in the neighbouring Muslim countries.

In conclusion, the Citizenship Amendment Act in India, when juxtaposed vis-a-vis Israel's immigration policy, exemplifies a historical context-driven approach to ensure the safety and well-being of religious minorities, without in any way, directly or indirectly, discriminating against its Muslim citizens. By contextualizing its provisions within a broader understanding of historical injustices, India aspires to provide a secure haven and a permanent home for those genuinely in need. This approach, far from undermining our secular principles, serves as a testament to India's commitment to upholding its constitutional values, while safeguarding the interests of religiously persecuted communities. It is through a nuanced perspective and a balanced discourse that we can strive to forge a harmonious society that embraces diversity and safeguards the rights of all its citizens.

As the most populous country in the world and one of the most influential emerging voices in the comity of nations today, India could not but respond to this challenge even from a purely human rights and humanitarian perspective. That it did so in spite of a cacophony of orchestrated protests at home speaks volumes for the courage, sagacity and statesmanship of political leadership.

__________________________________________________________________

Author: KBS Sidhu, retired in 2021 after 37 years of service as a Punjab cadre IAS officer.

Graphics have been generated by the author using “Dream Studio” #AI software.

kbs.sidhu@gmail.com