India's Rice Export Dominance Internationally: A Delicate Balance of Production, Procurement and Policy

India’s rice export policies must evolve to better reflect both domestic needs and global demand and put the farmers' welfare as its top priority, followed by food security.

Delicate Debate on Paddy Production and Export Policy

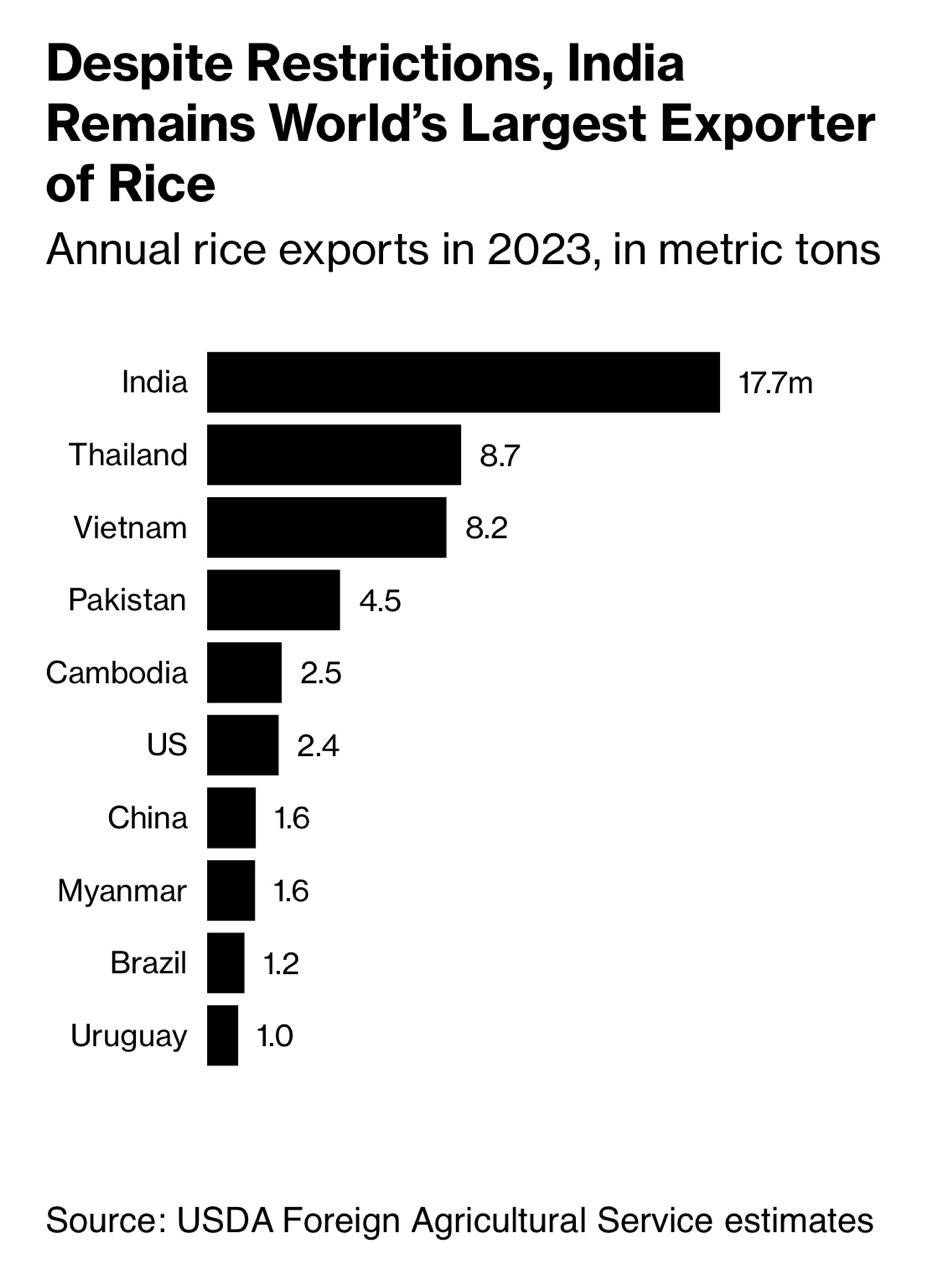

India continues to dominate global rice exports, despite intermittent government-imposed restrictions aimed at managing domestic supply and stabilising prices. These measures, often criticised as disruptive and irrational by pro-farmer lobbies and independent think tanks, are officially justified as efforts to safeguard the domestic market and strengthen nation’s food security. However, these have sparked widespread debates among policymakers, farmers, and economists alike. As India continues to maintain its status as the world’s leading rice exporter, critical questions emerge about the broader implications of these policies—both on global rice markets and on the livelihoods of Indian farmers, particularly in traditional paddy-growing states like Punjab and Haryana, as well as less prosperous agricultural regions such as West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh.

India’s Consistent Position as a Leading Rice Exporter

Despite various export restrictions, including bans on non-basmati rice and limits on parboiled varieties, India remains the world’s largest rice exporter. In 2023, India exported 17.7 million metric tonnes of rice, reinforcing its dominance in the global rice trade. This achievement is significant, given that these restrictions are often imposed to control inflation and ensure sufficient domestic supply, thus maintaining price stability.

However, these restrictions come with considerable consequences. International rice prices have surged due to uncertainty surrounding India’s export policies, affecting key markets across Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. The Thai benchmark price, for example, has risen by 26% over the past decade. While these restrictions may have helped ease domestic consumer prices or reduced the strain on the Indian government’s budget to fund its flagship food security programme, they have come at a significant cost to the Indian farmers, who are now grappling with virtually stagnating crop prices and rising production costs.

The Paddy Glut and Export Restrictions: An Unresolved Paradox

After a successful monsoon season, the Modi government relaxed some of the rice export restrictions in September, most notably lifting the total export ban on non-basmati white rice imposed in July 2023. Yet, the narrative of a domestic surplus persists, with reports of vast rice stockpiles lying unused in storage facilities across India. In Chhattisgarh, for example, millions of tonnes of rice have been reported as rotting due to inadequate infrastructure and missed export opportunities. Meanwhile, the Food Corporation of India (FCI), which procures grain at guaranteed prices to distribute to the poor, held 32 million tonnes of rice stock as of September 2024—a 39% increase from the previous year. This situation raises a crucial question: if India produces more rice than it needs, why maintain restrictive export policies?

Problem of Plenty?

This paradox is particularly glaring in Punjab and Haryana, where farmers are often vilified for over-cultivating water-intensive paddy. As anti-paddy sentiment gains ground, it is essential to recognise that the domestic surplus could be channelled into exports, benefiting farmers. In a country where Prime Minister Modi proudly touts the achievement of feeding 80 crore people through one of the world’s largest food security programmes, rice plays a critical role. Given the substantial budget allocated to this programme, and with rice stocks often deteriorating in FCI warehouses, the export restrictions seem contradictory. Exporting the surplus could stabilise domestic prices while also enabling farmers to earn a fair income through global sales.

Feeding India: The Role of Rice in the Food Security Programme

As noted before, India’s public distribution system, which feeds over 800 million people, is heavily reliant on rice. The FCI plays a pivotal role in this system by procuring rice at the Minimum Support Price (MSP) and distributing it nationwide through ration shops. By September 2024, the FCI held 32 million tonnes of rice, a 39% increase from the previous year, reflecting India’s agricultural strength but also exposing inefficiencies in managing food stocks. With hindsight, the export ban imposed ahead of the Lok Sabha elections appears overly cautious, creating a double burden: unmanageable rice stocks at FCI and minimal private procurement of paddy by millers and exporters during the last season.

Rice: A Pillar of India’s Food Security Efforts

With an ever-growing food security budget, rice remains central to India’s fight against hunger. However, there is a growing narrative that North-West Indian farmers, particularly in Punjab and Haryana, are over-exploiting water resources while draining the national exchequer. This perspective overlooks the critical role these farmers play in ensuring food security for millions. It also ignores the systemic challenges they face, such as inadequate infrastructure, unpredictable rainfall, and fluctuating market prices driven by export restrictions.

Firefighting in the Paddy Procurement Season: Punjab's Concerns

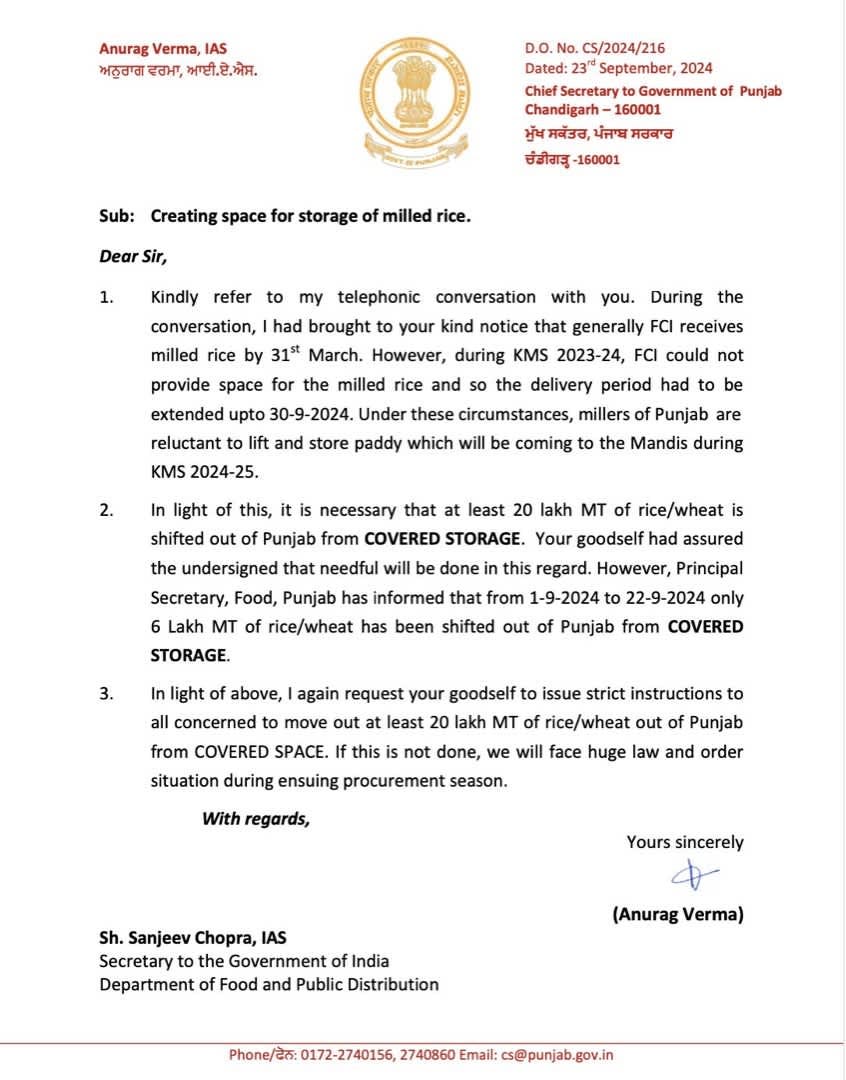

Recent communications between the Chief Secretary of Punjab and the Government of India highlight an urgent storage crisis that could disrupt the paddy procurement process for the 2024-25 Kharif Marketing Season (KMS). Punjab’s Chief Secretary raised several crucial concerns, primarily the shortage of storage space. The FCI was unable to provide adequate space for milled rice from KMS 2023-24, forcing an extension of the delivery period to 30th September 2024. As a result, Punjab millers have become hesitant to lift and store paddy for the upcoming season, fearing storage bottlenecks. Additionally, there is an urgent need to shift 20 lakh metric tonnes (MT) of rice or wheat out of Punjab to create space for the new crop.

As of 22nd September 2024, only 6 lakh MT had been shifted, well short of the 20 lakh MT target. This slow progress not only exacerbates the storage crisis but also raises concerns about potential unrest during the procurement season, as delays could frustrate farmers if the issue remains unresolved.

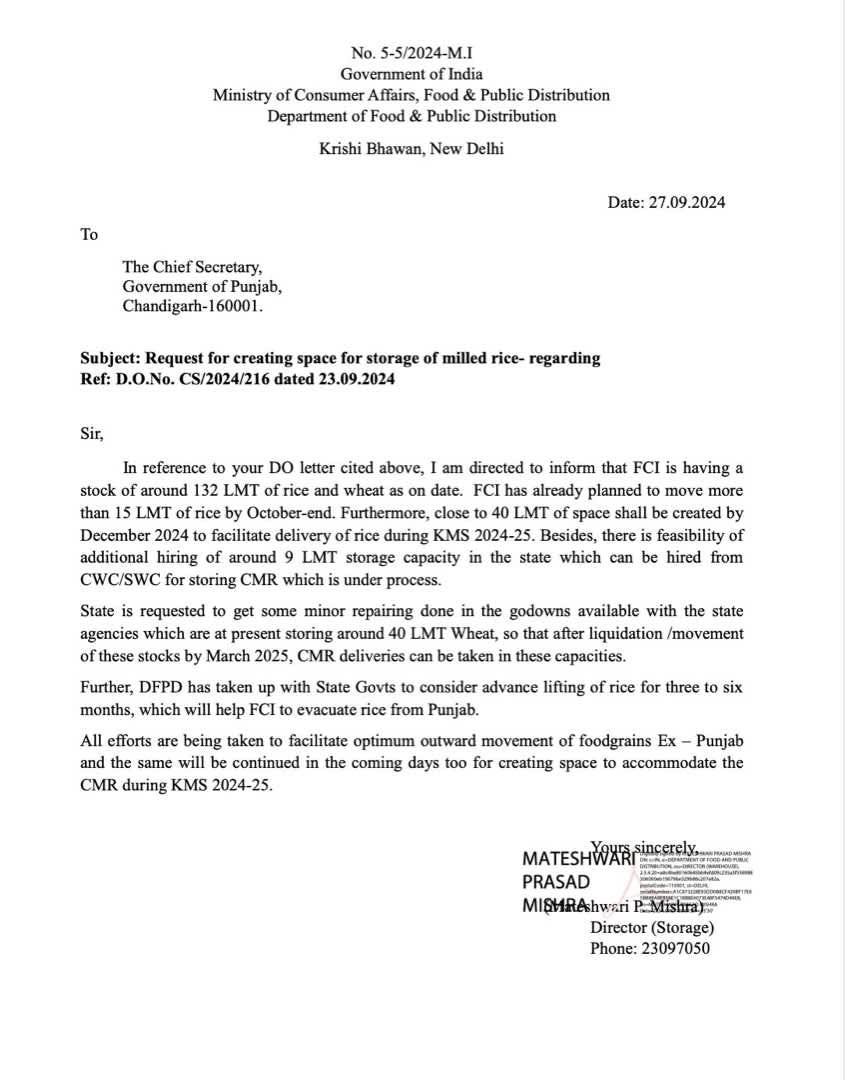

Government of India’s Response: Medium-Term Solutions, Immediate Concerns Unaddressed

In response, the Government of India outlined several measures to address the storage crisis. The FCI, holding 132 lakh metric tonnes (LMT) of rice and wheat, plans to move more than 15 LMT of rice out of Punjab by October-end. Additionally, it aims to create 40 LMT of storage space by December 2024, with another 9 LMT potentially available through hired storage from the Central and State Warehousing Corporations. The Central Government also requested state agencies to repair godowns storing 40 LMT of wheat and is considering advance rice lifting for 3-6 months to ease the burden.

While these steps show some commitment, they focus on medium-term solutions and fail to address the immediate crisis highlighted by Punjab. The proposed shifting of 15 LMT by October-end still leaves a shortfall of 5 LMT, and extending the timeline to December may not resolve the issue in time for the current season. Moreover, the reluctance of millers to lift paddy and the potential law and order disruptions are inadequately addressed.

Striking a Balance: Reforming Rice Policy for Farmers and the Nation

To address these issues, a more balanced policy framework is essential—one that combines an assured MSP with a transparent export mechanism. Empowering millers’ associations and cooperatives to play an active role in rice exports would give farmers greater control over their produce and ensure more efficient management of surplus stocks. Lifting restrictions on rice exports, particularly on parboiled varieties, would not only ease the domestic glut but also boost farmer incomes through global trade.

Encouraging the growth of farmers' cooperatives for rice exports would decentralise the process and provide farmers a stronger stake in the global market. At the same time, it is crucial to stop demonising paddy farmers as water-guzzlers and burdens on the national exchequer. The focus should instead be on improving agricultural practices and infrastructure to optimise water usage, while recognising the essential role these farmers play in feeding the nation.

A Call for Rational and Sustainable Policies

India’s rice export policies must evolve to better reflect both domestic needs and global demand. While securing food for millions remains a priority, it is equally important to support the farmers who ensure this security. The government should move toward policies that combine an MSP guarantee with cooperative export mechanisms, reduced export controls, and a more pragmatic approach to water management.

Paddy farmers, particularly in Punjab and Haryana, deserve recognition for their contributions to the nation’s food security. With the right reforms, India can continue to lead the world in rice exports while ensuring that its farmers thrive, its water resources are conserved, and its people remain well-fed1.

Export Bans on India's Agricultural Commodities: Humongous Losses to the Farmers

Main Agricultural Commodities Facing Export Bans