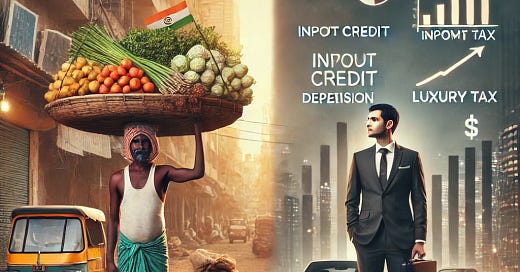

Introduction: The Unequal Tax Burden

The recent Oxfam report highlights a startling figure—50% of India's population, primarily from the bottom half, pays a staggering 65% of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Although the accuracy of this statistic has been contested by the government and several think tanks, it underscores an essential truth: the GST impacts every citizen, making all Indians indirect taxpayers. This article delves into the structural inequities within India's tax system, exploring how concessions, loopholes, and corporate structures overwhelmingly favour the wealthy, leaving the poorer half to bear a disproportionate share of the tax burden.

1. The Double Edge of GST: Input Credit Benefit and Inequality

One critical element in the GST system is the input credit mechanism, which allows businesses to claim tax credits at various stages of the value chain. Wealthier individuals and corporations, benefiting from input credits, ultimately face a lower effective GST rate. In contrast, the poor and middle class, who are the end consumers, lack this advantage and therefore pay the full rate. Thus, while GST is uniformly applied, its effective burden disproportionately affects those who cannot claim input credits.

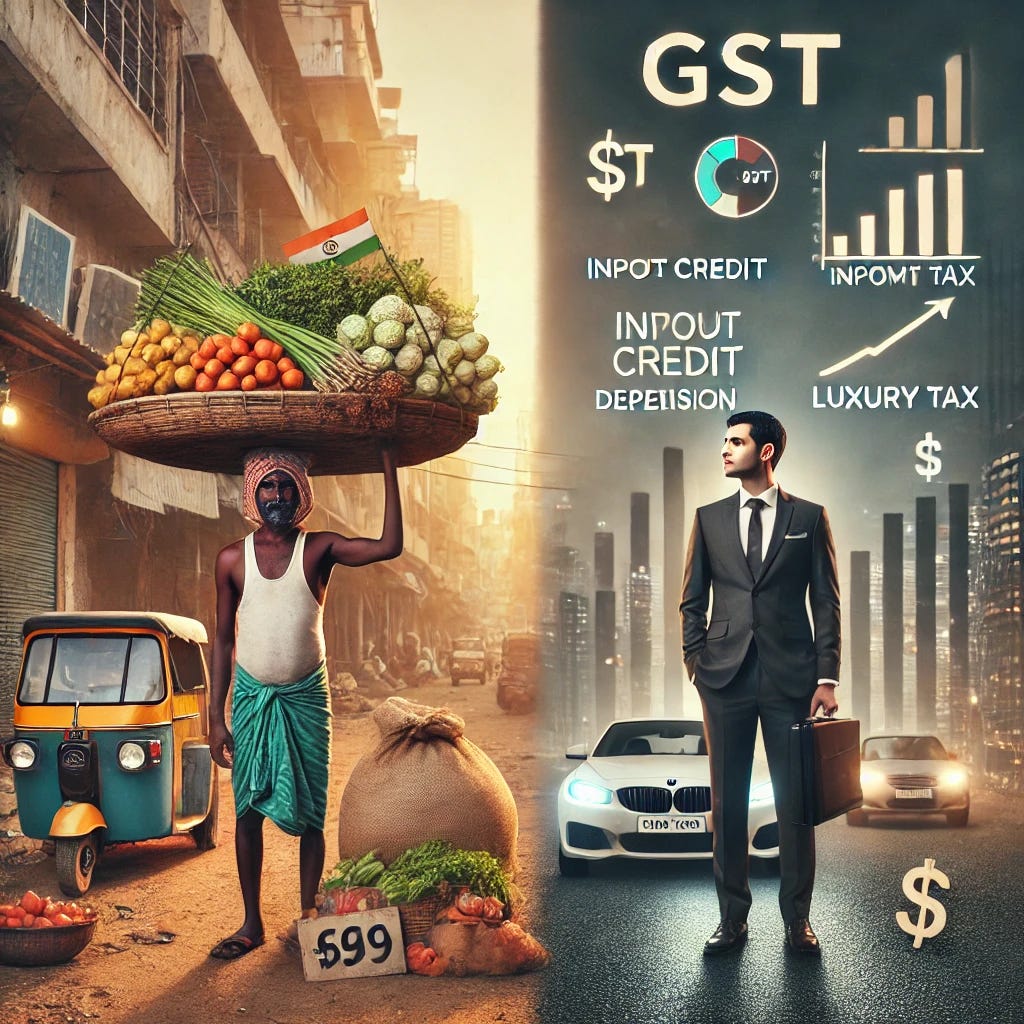

2. Corporate Tax Structures: Privileges for the Wealthy

A substantial portion of India’s high-income individuals conduct business through private or public limited companies. India’s corporate tax rates are among the lowest globally, which permits such entities to benefit from significantly reduced effective tax rates compared to individuals in the highest personal income tax brackets. Additionally, with numerous cesses applied to individual taxpayers but not to corporations, wealthy business owners effectively pay less tax than salaried middle-income earners.

3. Tax Benefits on Luxury Assets: Vehicles as Business Assets

It is common for high-net-worth individuals to use corporate structures to purchase luxury assets, such as vehicles, for ‘business purposes.’ These assets, often registered in company names, qualify for tax deductions on depreciation, reducing taxable income over several years. Additionally, the maintenance, insurance, and fuel costs for these vehicles are often debited as business expenses. To further lower their taxes, these individuals may finance these assets through bank loans, allowing them to claim interest expenses as tax deductions—an advantage out of reach for ordinary taxpayers.

4. Capital Gains Tax: Favouring High Net-Worth Individuals

Capital gains tax is another domain where high-net-worth individuals benefit disproportionately. The tax rate on long-term capital gains is around 20%, much lower than the highest income tax bracket. Furthermore, the holding period for listed equities to qualify as long-term capital assets is only one year, unlike other assets that require a three-year holding period. Until recently, long-term gains on listed Indian equities were nearly tax-free, save for a nominal Securities Transaction Tax (STT). Today, even with a 10% tax rate on long-term equity gains, the capital gains tax regime continues to favour high-net-worth individuals and creates a distinct advantage over regular income.

5. The Misconception of Agricultural Income Exemptions

While there is an enduring perception that rich farmers are evading taxes by declaring agricultural income, the reality is more nuanced. Landholding ceilings, such as Punjab’s 18-acre limit, and substantial input costs mean that agricultural income for large landholders is not as high as it appears. Even if a farmer achieves a gross yield between ₹50,000 to ₹1 lakh per acre, net income is minimal once expenses like interest, equipment depreciation, and input costs are accounted for. Therefore, claims that agricultural income tax exemptions benefit wealthy landowners often overlook the realities of agricultural economics.

Yet, it is also true that certain high-net-worth individuals misuse these agricultural exemptions as a front for money laundering. With some showing enormous agricultural incomes generated from minor activities, such as flower pots on their balconies, it is evident that this is not legitimate agricultural income but rather a money-laundering tactic. Such instances should undergo rigorous scrutiny, with any misrepresented income classified and taxed at the highest rate, along with penalties, penal interest, and possibly legal proceedings under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA).

Calling out these abuses is crucial, especially as the perception that farmers enjoy significant tax breaks persists. This issue diverts focus from the real problem: the misuse of agricultural income exemptions by non-farming high-income individuals.

Summing Up: Towards a Fairer Tax System

Income tax, by design, is progressive, meaning that those who earn more should contribute more. However, as illustrated by the Oxfam report, the GST burden falls disproportionately on the poor, challenging the notion of equitable taxation in India. As the Finance Ministry looks to introduce a new Income Tax Code, it is a fitting time to consider removing outdated deductions that disproportionately benefit the wealthy. Only by establishing a balanced tax structure, where the rich bear their fair share, can India advance toward its public investment goals, economic growth, and the $4 trillion economy envisioned for 2047—a vision clearly outlined by Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a pathway to a prosperous Bharat.

………The vision of our great leaders who fought for independence of India, seems to have shattered as the wealthy people have gripped the entire systems to their advantage. A balanced tax structure is a big dream for the common people who have almost lost hope for their economic advancement whatever the size of our economy is envisioned for 2047 or beyond……..

Fundamental flaw in the report is that it is looking at bottom 50%, which is a huge chunk. Inequalities can never be fully eradicated. There are many income levels in the bottom 50%. If the objective of the report is to see if any poor are burdened by taxes, then probably we should look at tax contribution by the bottom 10 or 15%. Similarly, how much privileged are the rich, we should look at top 5% and include all - direct and indirect taxes to see the contributions in taxes. The inequalities, that way, may not be far out of balance. Further, world has tested all models, from Adam Smith to Karl Marx to Keynes, nothing has worked to make people equal. I think a variation study by excluding top 5% and bottom 10%, could give some meaningful insights.