ED Attaches Properties Worth Rs 751.9 crore in National Herald Money Laundering Case

We answer some of the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) regarding attachment of movable and immovable property during the course of ED investigation under the PMLA, 2002.

ED's Decisive Action in the National Herald Case

In a significant development in the National Herald case, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) on Tuesday (November 21, 2023) provisionally attached properties valued at Rs. 751.9 crore, marking a pivotal moment in its money laundering investigation under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002. The ED, in an official tweet, stated: "ED has issued an order to provisionally attach properties worth Rs. 751.9 Crore in a money-laundering case investigated under the PMLA, 2002. Investigation revealed that M/s. Associated Journals Ltd. (AJL) is in possession of proceeds of crime in the form of immovable properties spread across many cities of India such as Delhi, Mumbai and Lucknow to the tune of Rs. 661.69 Crore and M/s. Young Indian (YI) is in possession of proceeds of crime to the tune of Rs. 90.21 Crore in the form of investment in equity shares of AJL."

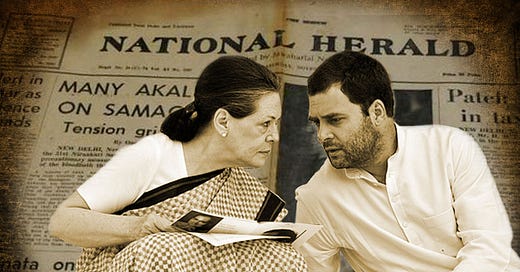

This significant step by the ED applies to properties associated with Associated Journals and Young Indian, implicating key figures such as Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi. The development has intensified public interest in the ED's authority under the PMLA to attach assets, including immovable property, during ongoing investigations or trial phases. Legal experts opine that this attachment signals an imminent filing of the formal complaint (chargesheet) by the ED in the Special PMLA Court.

Background and Legal Implications of ED's Investigation: FAQs Answered

The groundwork for the ED's money laundering investigation traces back to the proceedings initiated by the Metropolitan Magistrate of Delhi, who took cognizance of a private complaint on 26.06.2014. The Court held that seven accused persons including M/s Young India, prima facie committed offences of criminal breach of trust u/s 406 of IPC, cheating and dishonestly inducing delivery of property u/s 420 of IPC, dishonest misappropriation of property u/s 403 and criminal conspiracy u/s 120B of IPC. The revelation in the ED's tweet underscores the alleged possession of crime proceeds by M/s Associated Journals Ltd. and M/s Young Indian in the form of properties and equity investments, respectively.

ED's Findings: Alleged Misuse of AJL Assets and Acquisition by Young Indian

The court prima facie established that the accused in the National Herald case orchestrated a criminal scheme to acquire the valuable properties of Associated Journals Ltd. (AJL) through the company Young Indian (YI). AJL, originally allocated land at concessional rates for newspaper publication in various Indian cities, ceased its publishing activities in 2008 and shifted to commercial use of these properties. A critical point in the case was AJL’s obligation to repay a Rs. 90.21 Crore loan to the All India Congress Committee (AICC). However, in a controversial move, AICC wrote off this substantial loan as uncollectable and sold it to YI, a newly formed company with no apparent income, for a mere Rs. 50 lakh. This transaction was deemed as cheating towards AJL's shareholders and Congress Party donors, involving high-level office bearers of AJL and the Congress Party.

The Modus Operandi

The ED’s investigation further revealed that following the acquisition of AJL's debt, YI pressed for either repayment or conversion into equity shares in AJL. This demand led to an Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) of AJL, where a resolution to hike share capital and issue new shares worth Rs. 90.21 Crore to YI was passed. This resulted in the dilution of over 1000 shareholders' stakes to just 1%, effectively turning AJL into a subsidiary of YI and granting YI control over AJL's properties. The ED continues its investigation to unravel further details in this complex case.

Attachment of Property by ED: FAQs

These developments and the proactive measures taken by the ED have triggered extensive debates about the legal frameworks and the extent of powers granted to the ED, especially regarding the attachment of assets under the PMLA. In an effort to clarify these intricate legal aspects, we will explore 12 frequently asked questions, aiming to dilate upon the intricacies of this legal situation. It's important to acknowledge that while our intention is to provide thorough insights, our analysis should not be seen as a replacement for professional legal counsel. We advise those seeking a more in-depth legal understanding to consult with legal specialists. We also recognize that some repetition may occur in our answers, but our goal is to address each question comprehensively and independently, without the necessity of cross-referencing other responses.

1. What are the General Provisions Regarding Attachment of Property Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, the attachment of property is a crucial mechanism to combat money laundering. The general provisions regarding this can be primarily found in Sections 5, 8, and 17 of the Act. Here's a simplified explanation:

Provisional Attachment (Section 5): This section allows the Enforcement Directorate (ED) to provisionally attach any property believed to be "proceeds of crime". This attachment is temporary and is done to prevent any dealing, transfer, or disposal of the property. It can be done based on the report of an investigating officer but requires confirmation from an independent Adjudicating Authority within a specific period.

Confirmation of Attachment and Adjudication (Section 8): Once the property is provisionally attached, the matter goes before the Adjudicating Authority. This Authority, after considering the evidence and hearing the parties involved, decides whether the attachment should be confirmed or released. This process involves a careful assessment of whether the property in question indeed represents the proceeds of crime.

Powers to Search and Seize (Section 17): This section grants the authority to conduct searches of premises and seize records and property deemed to be involved in money laundering. The search and seizure are subject to certain conditions and procedures to ensure legal compliance and protect the rights of the persons involved.

The process of attachment under the PMLA is designed to ensure that properties acquired through illegal means are not disposed of or concealed while the investigation is ongoing. It's a measure to secure the property so that, if required, it can be confiscated after the completion of the trial. This process is closely monitored and regulated to safeguard the interests of all parties involved and to uphold the principles of justice.

2. Who Can Effect Attachment of Property Under the PMLA, and at What Stage?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, the authority and stage at which property can be attached are specifically outlined. Here's a detailed explanation:

Authority for Attachment: The power to provisionally attach property under the PMLA is vested in the Enforcement Directorate (ED), specifically with its officers not below the rank of Deputy Director. This is stipulated in Section 5 of the Act.

Stage of Attachment:

Initial Stage: The attachment of property can occur at the early stages of an investigation into money laundering. The ED, upon having reason to believe (based on material in their possession) that any person is in possession of proceeds of crime and such proceeds are likely to be concealed, transferred, or dealt with in a manner that may frustrate any proceedings relating to confiscation of such proceeds, can provisionally attach such property.

Duration of Provisional Attachment: This provisional attachment is initially valid for 180 days, as per the Act. Within this period, the matter must be presented before an independent Adjudicating Authority.

Confirmation Stage: The Adjudicating Authority, after considering the evidence presented, decides whether to confirm or revoke the attachment. If the Authority confirms the attachment, the property remains attached during the pendency of the trial related to the scheduled offence or the money laundering case.

This framework ensures that the attachment process is not arbitrary and is subject to oversight and judicial review. The idea is to prevent the disposal of assets acquired through illicit means while ensuring that the rights of the individuals are protected through a judicial process. The ED's power to attach property is a critical tool in the fight against money laundering, helping to ensure that assets involved in such activities are appropriately dealt with in accordance with the law.

3. How Long Does the Attachment Effected by the Officers of the Enforcement Directorate Last?

The duration of the attachment of property effected by officers of the Enforcement Directorate (ED) under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, follows a specific timeline:

Provisional Attachment Period: When the ED initially attaches property under Section 5 of the PMLA, this provisional attachment is valid for a period of 180 days.

Adjudication and Confirmation: Within these 180 days, the matter must be taken to the Adjudicating Authority. The Adjudicating Authority then assesses the case to determine whether the provisional attachment should be confirmed or released.

Post-Confirmation Duration: If the Adjudicating Authority confirms the attachment, the property remains attached until the conclusion of the trial for the related money laundering case. The duration of this period can vary based on the complexity of the case, the legal proceedings involved, and the judicial process.

Possibility of Extension: Under certain circumstances, the Special Court, upon request from the ED, may extend the provisional attachment period beyond 180 days. However, this is not a common occurrence and is subject to the discretion of the court based on the specifics of the case.

This structure of provisional attachment followed by adjudication and potential confirmation ensures that the attachment of property is not indefinite without judicial oversight. The process is designed to balance the need to prevent the disposal or concealment of illicitly obtained assets with the legal rights and interests of the individuals involved.

4. Is the Attachment Effected by the Officers of the ED Required to be Confirmed by a Judicial or Quasi-Judicial Authority, and Within What Time-Frame?

Yes, the attachment of property effected by the officers of the Enforcement Directorate (ED) under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, must be confirmed by a quasi-judicial authority, specifically, the Adjudicating Authority established under the PMLA. The timeframe for this confirmation process is defined in the Act:

Time-Frame for Confirmation: The provisional attachment order issued by the ED is valid for 180 days. Within this period, the matter must be brought before the Adjudicating Authority for confirmation.

Role of the Adjudicating Authority: The Adjudicating Authority, after reviewing the case and hearing the involved parties, decides whether to confirm, modify, or release the provisional attachment. This Authority is quasi-judicial in nature, meaning it has powers and procedures resembling those of a court of law or judge, and is empowered to make legal decisions and judgments.

Necessity of Confirmation: If the Adjudicating Authority does not confirm the attachment within these 180 days, the provisional attachment order lapses. The property then cannot remain attached under that specific order, ensuring a time-bound process and protection against indefinite attachment without proper review.

This provision ensures that the enforcement action initiated by the ED is subject to review and confirmation by an independent authority, providing a check and balance to the powers of the ED and safeguarding the rights of individuals and entities involved.

5. What Happens if the Attachment Effected by the ED Officers is Not Confirmed by the Adjudicating Authority Within the Stipulated Period?

If the provisional attachment of property effected by the officers of the Enforcement Directorate (ED) under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, is not confirmed by the Adjudicating Authority within the stipulated period, the following occurs:

Lapse of Provisional Attachment: The provisional attachment order automatically lapses if it is not confirmed by the Adjudicating Authority within the prescribed 180 days. This means the attachment of the property is no longer valid.

Release of Property: As a result of the lapse, the property that was provisionally attached is released and is no longer under the control or restriction placed by the ED under the PMLA.

No Further Restriction Without New Order: After the lapse of the provisional attachment, the ED cannot impose any further restrictions on the property unless a new provisional attachment order is issued, based on fresh evidence or circumstances.

Protection of Property Owner's Rights: This provision ensures that the property of an individual or entity is not indefinitely or unjustly attached without confirmation from an independent quasi-judicial authority. It serves to protect the rights of the property owner and ensures that the ED's powers are exercised with appropriate checks and balances.

The stipulation of a time-bound confirmation process by the Adjudicating Authority underscores the balance the PMLA seeks to achieve between effective enforcement against money laundering and protection of individual rights.

6. Does the Attachment Last During the Period of the Trial if the ED Files a Formal Criminal Complaint and the Special Court Takes Cognizance After the Attachment is Effected?

When the Enforcement Directorate (ED) files a formal criminal complaint (charge sheet) related to a money laundering case and the Special Court takes cognizance of it, the status of the attachment of property effected by the ED under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, is as follows:

Continuation of Attachment: Once the Special Court takes cognizance of the charge sheet filed by the ED, the attachment of the property continues for the duration of the trial. This means the property remains attached while the trial is ongoing.

Confirmation by Adjudicating Authority: Before this stage, the provisional attachment must have been confirmed by the Adjudicating Authority within the stipulated 10-day period. Once confirmed, the continuation of the attachment through the trial is a standard procedure.

Purpose of Continued Attachment: The rationale behind keeping the property attached during the trial is to ensure that assets deemed to be “proceeds of crime” are not dissipated, disposed of, or otherwise dealt with in a manner that could hinder the legal process and potential recovery or confiscation at the conclusion of the trial.

Conclusion of the Trial: Depending on the outcome of the trial, if the accused is found guilty, the attached property may be confiscated as per the provisions of the PMLA. If the accused is acquitted, the attached property would generally be released, unless there are other legal grounds for its continued attachment or confiscation.

This procedure underscores the PMLA’s objective to prevent money laundering and ensure that properties involved in such crimes are dealt with according to law, while also ensuring due process and judicial oversight throughout the investigation and trial process.

7. In Case of Immovable Property, Does the ED Take Over Actual Physical Possession of the Premises in Question?

Under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, when the Enforcement Directorate (ED) attaches immovable property, the approach to taking physical possession of the premises varies:

Attachment vs. Possession: The attachment of property by the ED primarily restricts the transfer, conversion, disposition, or movement of the property. It does not always equate to taking physical possession of the property. The primary objective is to prevent the property from being sold, transferred, or dealt with in any manner that hinders the legal process.

Physical Possession in Certain Cases: In some instances, depending on the specifics of the case and the nature of the property, the ED may take physical possession of the immovable property. This could be due to reasons like the risk of property damage, illegal activities being conducted on the premises, or to preserve the property's value. However, this is not an automatic consequence of attachment.

Legal Provisions and Orders: Whether physical possession is taken can depend on the orders of the Adjudicating Authority or the court. Specific conditions or situations might warrant such an action, and these would typically be outlined in the legal orders pertaining to the case.

Practical Considerations: Taking physical possession of immovable property can involve additional legal and administrative processes. The ED would need to ensure that all actions are compliant with legal requirements and are justified in the context of the investigation and the prevention of money laundering.

The decision to take physical possession of immovable property is not taken lightly and is usually accompanied by sufficient legal justification and compliance with procedural requirements. The primary goal remains the prevention of illegal transactions or disposal of the property during the course of the legal proceedings.

8. In the Event of an Acquittal, Does the Attachment Automatically Lapse?

If a trial under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, results in the acquittal of the accused, the status of the attachment of property by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) is as follows:

Release of Attachment: Typically, if the accused is acquitted in a PMLA case, the attachment of the property related to that case would lapse. This is because the attachment is premised on the property being the proceeds of crime. An acquittal generally implies that the prosecution was unable to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the property was indeed involved in or represents the proceeds of money laundering.

Judicial Orders: The release of the attached property is usually formalized through a judicial order. This order may come from the court that acquitted the accused or from another competent authority, as appropriate under the circumstances of the case.

Exceptional Circumstances: There can be exceptional circumstances where the attachment may not automatically lapse upon acquittal. For instance, if there are other ongoing investigations or cases related to the same property, or if there are specific legal provisions or court orders stating otherwise.

Right to Appeal: It is also important to note that the prosecution has the right to appeal the acquittal. During the pendency of such an appeal, the status of the attachment might be subject to the decisions of the appellate court.

The principle behind this is to align the outcome of the attachment process with the outcome of the judicial process, ensuring that property is not unjustly retained under attachment if the basis for such attachment (i.e., the criminal charge of money laundering) is not legally upheld.

9. In the Event of a Conviction, What Happens to the Attached Property? Is it Confiscated or Forfeited to the Central Government?

When a trial under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, results in a conviction, the fate of the property attached by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) is as follows:

Confiscation of Property: Upon conviction for an offence under the PMLA, the attached property, which is deemed to be the proceeds of crime, is liable to be confiscated. This means the property is legally taken over by the government.

Process of Confiscation: The process of confiscation is governed by the PMLA, where the court that convicts the accused has the authority to order the confiscation of the attached property. This is typically done through a judicial order following the conviction.

Forfeiture to the Central Government: Once confiscated, the property effectively becomes the property of the Central Government. The Act provides for the transfer of the rights and title of such confiscated property to the government.

Management of Confiscated Property: Post-confiscation, the management and disposal of the property are handled as per the rules and procedures laid down under the PMLA. The government may decide to manage, use, or dispose of the property in accordance with the legal provisions and in the manner deemed appropriate.

Rights of Legitimate Claimants: It is also important to note that the PMLA makes provisions to protect the rights of third parties who may have a legitimate claim or interest in the attached property. Such parties can approach the court to establish their claims.

The confiscation of property upon conviction serves the dual purpose of penalizing the offender and ensuring that the proceeds of crime are not retained by the offender or their associates. It's an essential component of the enforcement mechanism under the PMLA aimed at deterring money laundering activities.

10. In the Case of an Individual, Where His Property is Attached, What Happens to the Attachment in the Event He Dies During the Course of the Investigation or Trial?

If an individual whose property has been attached under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, dies during the course of the investigation or trial, the following occurs with respect to the attachment of the property:

Continuation of Proceedings: The proceedings under the PMLA, including the attachment of property, generally do not automatically cease upon the death of the individual. The legal process may continue against the estate or legal heirs of the deceased.

Attachment on the Estate: The attached property, as part of the deceased's estate, continues to be subject to the same legal restrictions that applied before the individual's death. This means the attachment remains effective against the property in question.

Legal Heirs as Representatives: The legal heirs or representatives of the deceased may be brought into the case as necessary parties. They represent the interests of the deceased's estate in the ongoing legal proceedings.

Adjudication and Confiscation: The Adjudicating Authority or the court will continue to assess the case based on its merits. If the property is found to be proceeds of crime, it may still be subject to confiscation or other legal actions as per the PMLA.

Rights and Obligations: The legal heirs inherit not only the property but also the liabilities and legal obligations associated with it. Therefore, any legal decisions regarding the attachment or confiscation of the property will affect the estate.

Settlement of Claims: If there are other claimants or creditors of the deceased's estate, their claims may also need to be settled as per the applicable legal framework, taking into consideration the attached property.

The continuation of the legal process after the death of the individual ensures that the objectives of the PMLA, particularly the prevention and penalization of money laundering, are upheld, while also considering the rights and interests of the legal heirs and other affected parties.

11. What are the Remedies Available Under the Law to a Person Who Wants to Challenge the Attachment Effected by the Enforcement Directorate?

A person who wishes to challenge the attachment of property effected by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, has several legal remedies available:

Appeal to the Adjudicating Authority:

The first step is to approach the Adjudicating Authority established under the PMLA.

This Authority is responsible for confirming the provisional attachment order issued by the ED.

An individual can present their case and evidence to contest the attachment during the hearing before the Adjudicating Authority.

Appeal to the Appellate Tribunal:

If the person is dissatisfied with the decision of the Adjudicating Authority, they have the right to appeal to the Appellate Tribunal for Money Laundering.

The Appellate Tribunal reviews the case and has the power to overturn or modify the decision of the Adjudicating Authority.

High Court Petition:

After the Appellate Tribunal, the next level of appeal is to the High Court.

A petition can be filed under the appropriate jurisdiction challenging the decisions of the lower authorities.

Supreme Court Appeal:

As a final recourse, an appeal can be made to the Supreme Court of India.

This is generally in cases where there are substantial questions of law involved.

Writ Petition:

In exceptional circumstances, where there are concerns regarding the violation of fundamental rights or other legal issues, a writ petition can be filed directly in the High Court or the Supreme Court.

Interim Relief:

At any stage of these proceedings, the person can apply for interim relief, seeking a stay on the attachment order until the final resolution of the legal challenge.

These remedies provide a comprehensive legal framework for individuals to challenge the attachment of their property, ensuring that their rights are safeguarded and that there is an opportunity for redressal in case of any grievance against the actions of the ED under the PMLA. The multi-tiered appeal process is designed to ensure fairness and justice in the application of the law.

12. If a Person is Not Mentioned by Name in the ECIR, Can His Property be Attached During the Course of Investigation?

If a person is not explicitly mentioned by name in the Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR) – which is the document initiated by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) for money laundering investigations under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002 – the circumstances under which their property can be attached during the course of the investigation are as follows:

Attachment Based on Association with Proceeds of Crime:

The PMLA allows for the attachment of property that is considered to be “proceeds of crime”.

If a person’s property is identified as being directly or indirectly derived or obtained as a result of criminal activity related to a scheduled offense under the PMLA, it can be subject to attachment, regardless of whether the individual’s name is mentioned in the ECIR.

Link to the Offense:

The crucial factor for attachment is the connection of the property to the money laundering offense, rather than the named status of the individual in the ECIR.

The ED must have reasonable grounds to believe that the property in question is involved in money laundering.

Due Process:

The attachment, even in cases where a person is not named in the ECIR, must follow the due process as laid down in the PMLA.

This includes provisional attachment, followed by confirmation from the Adjudicating Authority.

Opportunity for Defense:

Persons whose property is attached (named or unnamed in the ECIR) have the right to present their case and defend their property against the attachment order in front of the Adjudicating Authority and higher appellate authorities.

Judicial Review and Oversight:

The entire process is subject to judicial review, ensuring that the attachment is not arbitrary and is based on evidence linking the property to money laundering activities.

The focus in such scenarios is on the nature and origins of the property rather than solely on the individual’s named status in the ECIR. This is in line with the overarching objective of the PMLA to combat money laundering and prevent the disposal of property derived from such illegal activities.

Conclusion: Understanding the Future Course of Legal Proceedings and Asset Attachment by ED

As we anticipate the Enforcement Directorate (ED) filing its chargesheet with the Special PMLA Court, the formal legal proceedings are set to commence. Although the completion of these proceedings might take considerable time due to the nature of our legal system, which allows for appeals and revisions at various stages, it is important to note that the properties in question will remain under attachment throughout the duration of the trial. Through this article, we sincerely hope to have provided clarity and understanding regarding the legal procedures and the underlying objectives of the ED's asset attachment during both the investigation and trial phases.