Dr MS Gill—a Commemoration, not an Obituary

I share nuggets of my conversation with him— his views about important political events, including Rahul Gandhi's ordinance-tearing incident of 2013 & what the PM Dr Manmohan Singh ought to have done.

Early Encounters with a Legend

From our initiation into the Punjab cadre of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), the name Dr Manohar Singh Gill resonated as that of a legendary senior colleague. However, his commitments on Central deputation, including overseas assignments, meant that we didn't cross paths until he returned to serve actively in the state of Punjab. My technical initiation into the IAS was on 21st August 1984 at the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie. This period was during the aftermath of the highly unfortunate and condemnable Operation Blue Star. My first regular posting began as Sub-Divisional Magistrate (SDM) in Samrala, Ludhiana district, in August 1986, following an 8-month district training stint in Patiala.

A Shift in Governance and Gill's Return

In June 1987, the Government led by Surjit Singh Barnala was dismissed after a tenure of just two years. This came after the elections of 1985, which were conducted in the aftermath of the Rajiv-Longowal Accord. The dismissal led to the imposition of President's Rule, which remained in effect until 1992. During this politically tumultuous period, significant bureaucratic changes occurred, including the return of Dr MS Gill to the Punjab cadre. He was appointed as Financial Commissioner (Development) by Siddharth Shankar Ray, who was serving as the Governor of Punjab at the time.

Pioneering Development Initiatives

Dr Gill's innovative and pragmatic approach had a far-reaching impact on Punjab's infrastructure and agricultural sectors. He undertook extensive initiatives to revamp the rural road network, not just conducting repairs but also overseeing the expansion and construction of village link roads using modern, pre-mixed bitumen pavers. In the agricultural domain, Dr Gill was a vocal advocate for crop diversification, pushing for the introduction of oilseed cultivation as a viable alternative to traditional staples.

These initiatives were in line with the broader technology missions helmed by Sam Pitroda, a close associate of then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. Furthermore, Dr Gill initiated significant reforms in the cooperatives sector, aiming to improve efficiency and productivity. In the forest department, his reforms focused on sustainable forest management, promoting both conservation and commercial interests. Within the realm of Panchayati Raj institutions, Dr Gill worked to strengthen local governance, emphasizing transparency, accountability, and community involvement. Together, these varied efforts solidified his reputation as a dynamic and effective administrator.

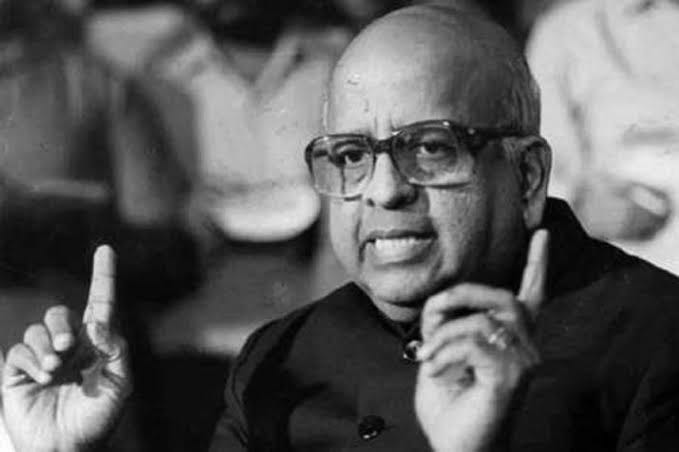

The Dilemma of Charisma

In retrospect, Dr Gill's towering public persona added another dimension to his influence. Not only was he a tall and handsome Jat Sikh officer with truly secular credentials, but his eloquence in both Punjabi and English also won him considerable acclaim. This growing profile, however, led to some unexpected consequences. Even esteemed superiors like Governor Siddharth Shankar Ray, colloquially known as 'Lord Sahib' among bureaucrats, seemed to grow somewhat insecure. There was a perception that Dr Gill's rising prominence was overshadowing even the Governor in both local and national media.

An Early Start to a Stellar Career

Dr Gill embarked on his career in the Indian Administrative Service in 1958, joining the Punjab cadre at the young age of 22—well before the state underwent its significant reorganisation in 1966. In his early years, he served as Principal Secretary to Sardar Parkash Singh Badal during his first, albeit brief, tenure as Chief Minister of Punjab. Intriguingly, despite being the most senior and seemingly the most suitable candidate, Dr Gill was not appointed as the Chief Secretary of Punjab between 1987-89. This could perhaps be attributed to Governor Siddharth Shankar Ray's cautious approach, as discussed earlier; it's conceivable that even the Governor was somewhat in awe of Dr Gill's capabilities. Regardless, both at that time and in retrospect, I remain convinced that he would have been the most fitting individual for the role, especially considering the turbulent circumstances Punjab was navigating.

National Roles with a Punjab Focus

Although passed over for the position of Chief Secretary of Punjab, Dr Gill transitioned to a Central deputation, taking on the role of Secretary of Chemicals and Petrochemicals. Yet, his enduring connection and deep-seated commitment to Punjab were never far from the surface. His initiatives included bringing the Central Institute of Plastic Engineering and Technology to Amritsar and laying the foundation for what would become the National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER) in Chandigarh. Owing to his high all-India seniority, he was also on the cusp of being appointed as the Cabinet Secretary to the Government of India—a position he more than deserved, and arguably, no one else was better suited for.

Navigating Political Waters

Though Dr Gill was a strong contender for the post of Cabinet Secretary, the political currents flowed in a different direction. Influences within the Muslim lobby managed to convince Prime Minister Narasimha Rao that appointing Zafar Saifullah could bring significant electoral dividends in the upcoming Lok Sabha elections. Saifullah had not even been empanelled to serve as an additional secretary to the Government of India, yet he was considered for this elevated role.

The Election Commission Interlude

As a consolation prize, Dr Gill was appointed as an Election Commissioner in the Election Commission of India (ECI), a role that seemed more symbolic than substantial given the indomitable presence of TN Seshan as the Chief Election Commissioner. Indeed, Seshan's overpowering style of functioning meant that Dr Gill barely saw any action initially. Disappointed and idle, Dr Gill took a sabbatical to his family farm in Shivpuri district, Madhya Pradesh. A candid photograph of him in shorts, riding a tractor, made its way to the national media. Ironically, this episode highlighted what was increasingly viewed as the non-consultative, if not dictatorial, governance style of TN Seshan.

A Personal Connection to Amritsar

Dr Gill's ancestral roots in Aladinpur near Tarn Taran, once part of Amritsar district, forged a personal connection between us during my tenure as Deputy Commissioner in Amritsar. He would occasionally consult with me about development projects in his home village and updates on the Central Institute of Plastic Engineering and Technology (CIPET), an institution he essentially founded. These interactions were not just professional; they underscored his deep-seated attachment to his ancestral land.

Preparation for an Electoral Foray, Under the Radar

As India approached the general elections of 1996 and the Narasimha Rao Government was nearing its end, Dr Gill expressed a desire to register as a voter in his ancestral village. Given his ownership of immovable property in the area, and his commitment to have his existing New Delhi vote annulled, the process was straightforward. Yet Dr Gill wished to keep this decision low-profile to avoid media attention. To honour his request, we managed a discreet operation. He made an unpublicised visit to Amritsar, stayed at the Guru Nanak Dev University guesthouse, and had his photo taken for the voter ID card after sunset. By morning, he was on a train back to Delhi, new voter ID in hand, but away from the media spotlight.

Rumours of a Political Foray

Given Dr Gill's historical association with Parkash Singh Badal and his somewhat sidelined role as an Election Commissioner under TN Seshan, speculation began to circulate that he might contest the Lok Sabha elections from Tarn Taran on a Shiromani Akali Dal ticket. The buzz gained traction, especially in the wake of the underwhelming performance by the Congress government led by Harcharan Singh Brar and the Shiromani Akali Dal's by-election win in Ajnala Vidhan Sabha in 1994.

Changing Political Winds in Punjab

The political climate in Punjab was showing signs of transformation, particularly in the Majha region. With the Punjab Vidhan Sabha elections scheduled for February 1997 still on the horizon, a Lok Sabha victory in the predominantly rural constituency of Tarn Taran in 1996 would be a strong indicator of rural Punjab's leanings. And who could better represent this change than Dr Manohar Singh Gill, a native son with deep roots in the area?

Change in the Election Commission of India

This, however, was not to be. Soon after, the Supreme Court rendered its judgement, making it clear that the Chief Election Commissioner was merely 'first among equals' and not a supremo within the three-member Election Commission of India. After TN Seshan vacated his office in 1996, Dr Gill was elevated to the role of Chief Election Commissioner due to his seniority, while Mr GVG Krishnamurthy served as the other Election Commissioner.

My Career Transition and Overseas Training

By August 1996, I had moved on from my post as the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar. Subsequently, I was selected for a one-year overseas training programme at the University of Manchester. I was slated to pursue an MA in Economics, with a focus on Development Administration and Management, sponsored by the Government of India.

Political Changes in Punjab

During my time at Manchester, I learned that Sardar Harcharan Singh Brar was removed from his position as the Chief Minister of Punjab. He was replaced by Mrs Rajinder Kaur Bhattal by the Congress high command. She had only a few months in office to make her mark before the impending Vidhan Sabha elections, scheduled for February 1997.

Model Code of Conduct and Political Reactions

Mrs Bhattal was enacting a series of bold and innovative measures, causing apprehension within the Shiromani Akali Dal that she might actually turn the political tide in her favour. As a response, they strongly urged Dr MS Gill, who was now the Chief Election Commissioner, to promptly impose the Model Code of Conduct, alleging misuse of official position by the Bhattal Government for electoral gains. In response to this request, the Election Commission activated the code shortly after Christmas in 1996. This effectively halted the decision-making momentum of the Bhattal Government, prompting strong objections from the Congress Party.

A Personal Encounter with Dr MS Gill

In 2013, I had the opportunity to meet Dr MS Gill at a family wedding function in New Delhi. By then, he had completed his term as a Union Minister in the Manmohan Singh Government, having been asked to step down in July 2011, in my opinion, as a scapegoat. It's important to clarify that the controversies surrounding the 2010 New Delhi Commonwealth Games primarily concerned construction work relating to various stadiums, tasks carried executed by agencies under the aegis of the Urban Development Ministry, such as the DDA, NBCC, CPWD, and NDMC. Dr Gill, in his role as Sports Minister, was not even remotely concerned. Even after his resignation as a Union Minister, he, of course, continued as a Congress Rajya Sabha member from Punjab until 2016, rounding off a 12-year tenure (2002-2016) in the Upper House.

Fully cognisant that he was under no obligation to respond, I seized the moment to directly inquire, despite him still being a sitting Rajya Sabha MP for the ruling Congress Party, "Did you initiate the code of conduct a month in advance in Punjab ahead of the 1997 Vidhan Sabha elections?"

Dr Gill's Candid Response

Having imbibed a couple of goblets of red wine, a drink he was then quite fond of, Dr Gill spoke with refreshing candour. He explained that he aimed for an unbiased decision and did not wish his past relationship with Parkash Singh Badal to fuel any allegations of partisanship from the Congress Party. Consequently, he requested Mr GVG Krishnamurthy, the only other Election Commissioner at the time, to undertake an extensive tour of Punjab and consult with all relevant political stakeholders. Acting on Mr Krishnamurthy's comprehensive on-ground report, which recommended the immediate enforcement of the code, Dr Gill took the necessary steps. He also mentioned that delaying the imposition of the code of conduct by about a fortnight wouldn't have made a significant difference, adding that he believed the Congress was already on course for a defeat in the forthcoming elections.

Dr Gill's View on Rahul Gandhi's Ordinance-Tearing Drama

During the same meeting, the conversation shifted to Rahul Gandhi's later controversial act of tearing up an ordinance. This ordinance had been approved by a Cabinet meeting led by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on 24 September 2013, and it would have allowed convicted politicians to contest elections. Dr Gill didn't mince words; he described the act as "immature" or words to that effect. He used this incident to emphasise the level of dignity, decency and decorum expected in public office, even for a Member of Parliament.

On Dr Manmohan Singh's Response

Dr Gill continued by remarking that if he were in Dr Manmohan Singh's shoes, he would have quietly faxed his resignation to the Rashtrapati Bhavan and returned to India as a private passenger, in an ordinary commercial flight. He expressed that Dr Manmohan Singh lacked the moral courage to take such a bold step. According to him, whether it was a matter of the man clinging to power, or power clinging to the man, was uncertain. However, resigning at that juncture would have solidified Dr Manmohan Singh's legacy, he opined.

Responsibility to Mrs Sonia Gandhi

When I questioned him on whether such a move wouldn't be unfair to Mrs Sonia Gandhi, who had appointed Dr Manmohan Singh as the Prime Minister in 2004, Dr Gill conceded the point. He acknowledged that Dr Manmohan Singh had fulfilled diligently the responsibilities entrusted to him by Sonia Gandhi and had remained loyal. Nonetheless, he pointed out that the ordinance-tearing episode did not just humiliate Dr Manmohan Singh personally while he was abroad on official duty, but also brought disgrace to the position of the Prime Minister of India in the eyes of the international media.

Dr Gill's Future Plans and Aspirations

Before the conversation could turn to his own exit from the Union Council of Ministers, other guests began to gather, diverting his attention. I did manage to ask him about his future plans. Dr Gill's answer was succinct: "Write occasionally, travel, and enjoy my drink, and of course, write my memoirs." Whether he ever got around to penning his autobiography remains unknown to me, but it would undoubtedly make for a compelling read.

A Glimpse into His Past and Longevity Goals

About a year ago, I happened to watch Dr MS Gill's interview on a local Punjabi YouTube channel. He fondly reminisced about his time as Deputy Commissioner of Lahaul-Spiti in undivided Punjab. He also shared tales of how Sardar Partap Singh Kairon, the legendary Punjab Chief Minister, used to keep IAS officers on their toes by scheduling meetings in remote locations. During this interview, Dr Gill confirmed that he was in excellent health. Inspired by individuals like the late Khushwant Singh, who almost lived to a hundred, Dr Gill, born in 1936, mentioned his own aspiration to reach that milestone. Like a seasoned batsman, he said he was aiming to steadily advance towards his 90s.

An Unexpected Turn and Reflections

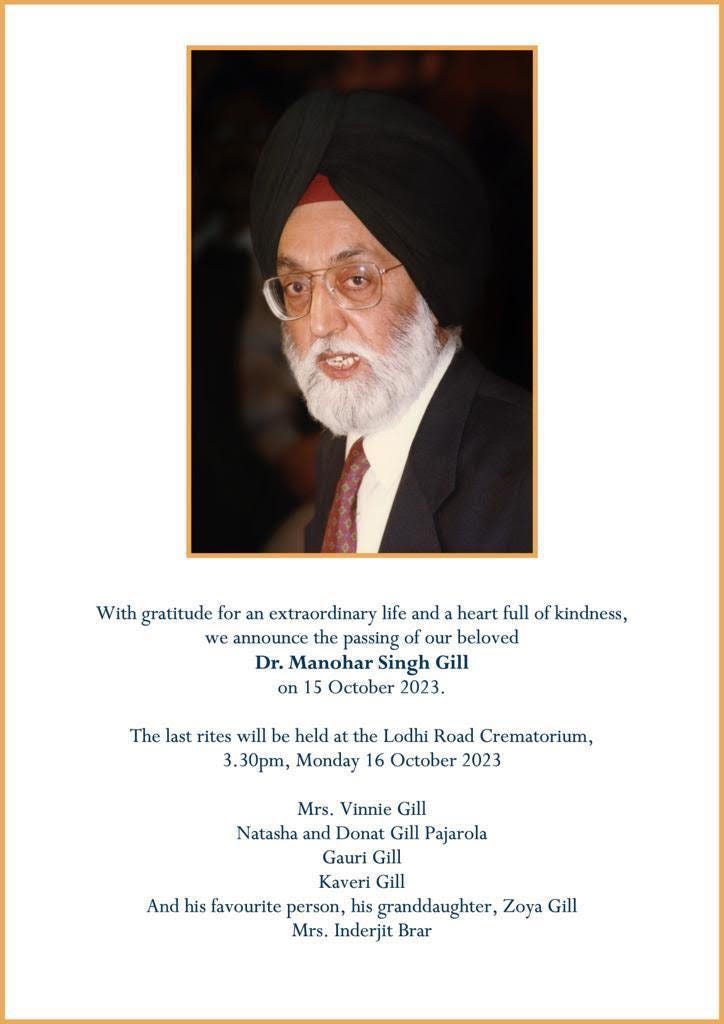

Sadly, the hopeful vision of longevity was not to be realised for Dr MS Gill. Family sources suggest that incorrect medication led to his hospitalisation, and though he was discharged, his health took a turn for the worse. His peaceful demise on 15th October 2023 triggered the thoughts and reflections that I've set down here, albeit without perfect chronological order and without malice towards anyone.

A Lasting Legacy in Electoral Democracy

While Dr Gill's contributions to Punjab's development are often cited and undoubtedly significant, in my view, his most impactful work lies in the realm of Indian electoral democracy.

The Festive Nature of Elections

TN Seshan's tenure as the Chief Election Commissioner had rendered Indian elections so restrictive that even a small flag hanging from a tree could be deemed a violation of the election code of conduct, punishable under Section 188 of the IPC. When Dr Mahohar Singh Gill took over the role, he made it clear that India's general elections should be seen as the country's greatest festival, celebrated by citizens of all communities. He insisted that while the role of money, muscle power, and alcohol would be strictly curtailed by election observers and field machinery, the enthusiastic canvassing and sloganeering that are part of vibrant democracy should not be suppressed.

Decentralising the Election Commission's Role

Dr Gill also emphasised that it's not solely the Chief Election Commissioner in Nirvachan Sadan at Delhi that conducts general elections, but rather a massive collective effort involving lakhs of polling officers, presiding officers, and security personnel. These officers, supported by Election Observers, Chief Electoral Officers of the states, District Collectors and the Election Commission's headquarters, carry out the complex process. In one notable meeting, he remarked, "After the issue of the election notification, the Election Commission can go to sleep. Our laws and systems are so robust that the entire process will proceed smoothly. The three wise men can then wake from their slumber to sign the notification of the elected or 'returned' candidates to b forwarded to the President or the Governor of the State."

The Unsung Hero: The Voter

Dr Gill consistently emphasized that the true heroes of this dramatic and vibrant democratic spectacle are not the politicians or the officers but the humble voters. These electors, who brave various elements like rain, sun, snow, and dust storms to stand in long queues, are the backbone and soul of our democracy. Dr Gill believed that the Election Commission's primary role should be to encourage these voters to participate actively and in large numbers, without succumbing to fear, undue pressure or inducement.

A Lasting Legacy

Dr MS Gill lived a life of utmost dignity, whether he was serving in a high public office or simply as an ordinary citizen. A true son of Punjab and of India, he never minced words and always spoke his mind. He doesn't need any posthumous honours for his legacy to be remembered. His impact is imprinted on the hearts and minds of all those whose lives he touched, both directly and indirectly.

Dr Manohar Singh Gill, RIP.

I have shared my autobiography with you via email. Surjit Singh Puri had created the post of Deputy Secretary ( Coordination) and he appointed me on that post. It included the charge of Vigilance. Vigilance Bureau sent two cases for sanction of prosecution. I wrote notes opposing the sanction because of lack of proof. The Chief Secretary agreed with my notes and forwarded the files to the Chief Minister. Manohar Singh Gill was the Principal Secretary to the CM. He called me to his room and rebuked me. I told him that my view on the cases was endorsed by the CS and he should talk to him. I also told him that I was not a sycophant or a subservient to a politician. He was surprised by my reply. My ACR was graded Outstanding by my Minister but Manohar Singh Gill got it downgraded as Very Good by Chief Minister, Prakash Singh Badal.

Towering personality. Many years ago , I saw and heard him being interviewed by Najam Sethi on Pakistani show , where he extensively spoke about new voting machine India had just introduced and about independence of election commision. Najam was demonstrating the stark contrast of Pakistan and Indian electoral system. A great loss for Punjab and India. I am sure you will always want to own and proud association you had with him through your professional and personal interactions. May waheguru provide peace to his soul which he so richly deserves.