Detained without trial: Examining the Evolution of Preventive Detention in India

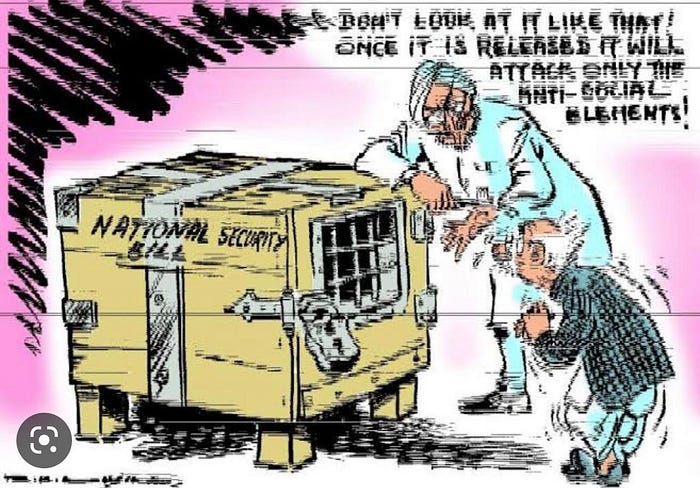

National Security Act, 1980 is often seen as a tool to detain persons without trial with no provision of bail, for an offence they have NOT committed.

Preventive Detention — the basic concept

Preventive detention is a highly contested, if not a controversial legal provision, placed ironically in the Part III of the Constitution of India that deals with the Fundamental Rights. It allows the government to detain a person without a trial or formal charges, on the basis of suspicion or apprehension that they may engage in illegal or dangerous activities prejudicial to the integrity of India or to public order, in the future. Unlike punitive detention, which is used to punish a person for a specific offence that they have committed, preventive detention is used to prevent future offences or activities or threats to public safety.

In India, preventive detention is allowed under certain circumstances, including those under the National Security Act (NSA), 1980. Its previous avatar was the draconian Maintenance of Internal Security Act, which was enacted in India in 1971, during the time of Indira Gandhi’s emergency regime and repealed in 1977 after she was voted out of power.

Draconian measures in the British Raj

During the British Rule in India, the law used for preventive detention was the Defence of India Act, 1915 and its amendments. The act was originally passed to deal with the exigencies arising from World War I, but was later used by the colonial government to suppress political dissent and to maintain law and order in the country.

Under the Defence of India Act, the colonial government had the power to detain individuals without trial for a period of up to two years, if they were deemed to be a threat to public safety or security. The act was widely used to arrest and detain Indian freedom fighters and other political activists who were campaigning for independence from British rule.

The act was amended several times during its existence, with the most significant amendments being made during the period of the Quit India Movement in 1942. The act was finally repealed in 1947, following India’s independence from British rule.

Why is it in news now?

Following Punjab Government’s recent decision to invoke NSA to detain the self-styled pro-Khalistan idolgue, Amritpal Singh, who is still at large, the curiosity as well as interest of the general reader as regards the basic framework of this statute has suddenly increased. Hence, this article.

National Security Act, 1980

NSA is a law that empowers the government to detain a person without trial for up to 12 months if they are deemed to be a threat to national security or public order. The law has been criticized by human rights organizations and legal experts for its potential misuse and for being a violation of the right to liberty and due process. However, the government has argued that the law is necessary to protect the integrity and sovereignty of India, particularly in the face of threats such as terrorism, insurgency, and communal violence.

The circumstances in which the NSA can be invoked include, preventing any person from acting in any manner prejudicial to the defence of India, the relations of India with foreign powers, or the security of India. Other grounds include the maintenance of Public order or the maintenance of supplies and services essential to the community The law has been used in various instances, including against separatist leaders in Jammu and Kashmir and against activists and so-called journalists who have tried to illegally incite or instigate the people against the government’s policies.

NSA case is NOT an FIR: It should be understood that a detention order under the NSA is not equivalent either to an arrest made by the police, with or without a warrant, following an FIR or the remand order of a judicial magistrate. Since, these proceedings are preventive in nature, the normal provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) such as bail, including anticipatory bail, do not apply. An NSA case does NOT lead to framing of formal charges by a competent jurisdictional court, leading to a trial, which can have only two possible outcomes — conviction or acquittal. Once the NSA term has been served or the detention order revoked earlier, no stigma of either a pending criminal case or conviction remains.

ADM Jabalpur Case

The ADM Jabalpur case, also known as the Habeas Corpus case, was a landmark judgment of the Supreme Court of India delivered on April 28, 1976, during the period of Emergency declared by the government in 1975. The case arose from a writ petition filed by four detenus challenging their detention under the then Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA).

The central question before the Supreme Court was whether a person’s right to life and personal liberty, guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution, could be suspended during an Emergency. The government argued that during an Emergency, the President could suspend the right to move the courts for the enforcement of Article 21, effectively taking away a person’s right to seek release from detention through a writ of habeas corpus.

In a majority decision, the Supreme Court held that during an Emergency, a person’s right to life and personal liberty could be suspended, and that the President’s order suspending the right to move the courts for the enforcement of Article 21 was valid. The majority judgment held that in the absence of the right to move the courts for the enforcement of Article 21, there was no remedy available to a person who was detained unlawfully.

This judgment was widely criticized and considered a low point in the history of Indian democracy, in particular for the higher judiciary. It led to protests and widespread condemnation from civil society and the legal fraternity, who saw it as a betrayal of the principles of the Constitution and the rule of law. The judgment was eventually undone in the year 1978 by the 44th Constitutional amendment, under the Janata Government lead by the Prime Minister Morarji Desai.

Constitutional safeguards re-introduced in 1978

The 44th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1978 made several significant changes to the Constitution of India with regards to preventive detention, Article 21, and its suspension during emergencies. The main features of the 44th Amendment Act in this regard are as follows:

Preventive detention: The 44th Amendment Act made significant changes to Article 22 of the Constitution, which deals with preventive detention. It provides that a person who is detained under a preventive detention law must be informed of the grounds of detention, and has the right to make a representation against the detention. The law also provides for the constitution of an advisory board to review the detention and make recommendations to the government.

Article 21: The 44th Amendment Act expanded the scope of Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to life and personal liberty. The amendment provided that no person shall be deprived of their life or personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law. This means that any law that deprives a person of their life or personal liberty must be fair, just, and reasonable.

Emergency provisions: The 44th Amendment Act placed certain restrictions on the power of the President to declare a state of emergency. It provided that the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 cannot be suspended even during a state of emergency. The amendment also placed restrictions on the power of the government to suspend the fundamental rights of citizens during an emergency.

Overall, the 44th Constitutional Amendment Act strengthened the safeguards against arbitrary detention and expanded the protection of the right to life and personal liberty. It placed limitations on the power of the government to suspend fundamental rights during emergencies, thereby ensuring that the basic rights of citizens are protected even in times of crisis.

Return of MISA in a new avatar?

The National Security Act, 1980 was enacted by the Indian government, when Mrs Indira Gandhi returned to power, with the stated objective of dealing with threats to national security and public order. The law allows for the detention of individuals who pose a threat to national security or public order, without trial or conviction.

The basic framework of the NSA includes the following provisions:

Grounds for detention: The government can detain a person under the NSA if it has reason to believe that the person is a threat to national security or public order. The grounds for detention must be specific and clear.

Detention order: The detention order must be issued by an officer of the government authorized by the state or central government. The order must be communicated to the detained person, ordinarily with five days and the detained person must be informed of the grounds for detention.

Advisory Board: The detained person has the right to make a representation against the detention before an advisory board, which is constituted by the government. The advisory board has the power to examine the grounds of detention and make recommendations to the government.

Period of detention: The initial period of detention under the NSA is up to 12 months, and the detention can be extended for up to two years if the government believes that the detained person continues to be a threat to national security or public order.

Review: The detention order and the extension of detention can be reviewed by the state government or central government at regular intervals.

Judicial review: Any person detained under the NSA has the right to challenge the detention before a constitutional court. The court can order the release of the detained person if it finds that the detention is not justified.

Remedies available to the detenu

A person who has been detained under the National Security Act (NSA) has several remedies available to challenge their detention. These include:

Making a representation before an Advisory Board: Under the NSA, a detained person has the right to make a representation before an Advisory Board, which is constituted by the government. The Advisory Board has the power to examine the grounds of detention and make recommendations to the government.

Filing a writ of habeas corpus: A detained person can file a writ of habeas corpus before the High Court or the Supreme Court challenging the legality of their detention. The court can order the release of the detained person if it finds that the detention is not justified.

Seeking a review of the detention order: The detention order and the extension of detention can be reviewed by the state government or central government at regular intervals. A detained person can request a review of their detention order and present evidence to support their release.

Filing a writ of certiorari: A detained person can also file a writ of certiorari before the High Court or the Supreme Court to challenge the legality of the detention order.

It is important to note that while these remedies are available, the process can be lengthy and complex, and the detained person may remain in custody during the pendency of the proceedings. Additionally, the burden of proof is on the detained person to prove that their detention is not justified, which can be challenging in cases involving national security or public order.

Summing up — Preventive detention, a necessary evil?

In summary, preventive detention is a legal tool that allows the government to detain a person without trial or conviction in order to prevent him or her from committing a future offence. The Constitution of India and the National Security Act, 1980 no doubt provide for preventive detention under certain circumstances, but the detention must adhere to the statutory procedural safeguards and is also subject to judicial review.

In conclusion, preventive detention under the NSA is a necessary evil that must be used with caution and with strict adherence to the safeguards provided under the law. While it may be necessary to protect national security and public order under certain extenuating circumstances, it must not be used as a tool to suppress dissent or silence political opponents. The use of preventive detention must be balanced against the protection of individual liberties and the right to due process, which are fundamental to a democratic society. This is a difficult balance to maintain, even during the best of the times.

_________________________________________________________________

The author superannuated as Special Chief Secretary, Punjab in July, 2021, after nearly 37 years of service in the IAS.

He can be reached on kbs.sidhu@gmail.com .