Bodh Poornima Reflections: Parallels Between Buddha’s Dhamma and Communism

As we commemorate Bodh Poornima, let us renew our quest for truth, equity, and inner liberation—not through dogma or political absolutism, but through compassionate inquiry and fearless dialogue.

Bodh Poornima: A Global Salute to the Light of Enlightenment

Today, on the auspicious occasion of Bodh Poornima, celebrated across the world as the day of Buddha's enlightenment, we extend our heartfelt felicitations to all. Regarded by hundreds of millions as a leading and lasting apostle of peace, Gautama Buddha (circa 563 BCE – 483 BCE) remains inextricably woven into the Indian psyche. While only around 1.5% of Indians formally identify as Buddhists today, the cultural and philosophical legacy of Buddha transcends religious boundaries. His life story and teachings continue to inspire philosophers, reformers, revolutionaries, and the common person alike, cutting across lines of caste, class, religion, and ideology.

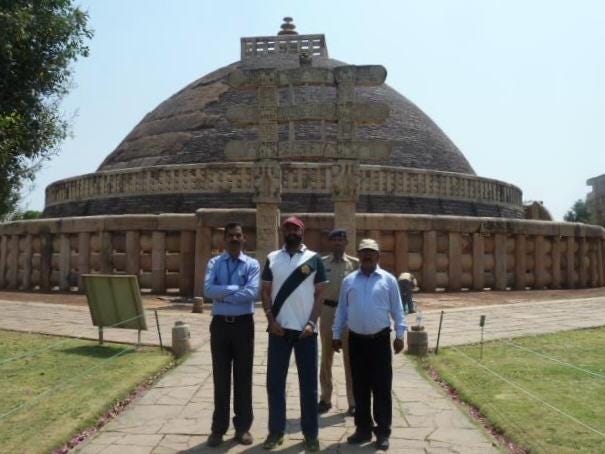

It was under the Bodhi Tree—a sacred fig tree in Bodh Gaya, located in modern-day Bihar—that Prince Siddhartha attained supreme enlightenment around 528 BCE, becoming the Buddha, or "the awakened one." The Mahabodhi Temple, which stands there today, is one of the most revered sites of pilgrimage in the Buddhist world. However, Buddha did not begin preaching immediately. It was only later, in Sarnath (near modern-day Varanasi), that he delivered his first sermon, known as the “Dharma Chakra Parivartana”—the Turning of the Wheel of the Law. This foundational act of expounding the Dhamma marked the beginning of the Buddhist Sangha and formal dissemination of his teachings.

From Ashoka to Ambedkar: The Dharma Chakra and India's Constitutional Soul

The symbol of that turning wheel—the Dharma Chakra—was later embraced by Emperor Ashoka (reigned circa 268–232 BCE), India’s most famous Mauryan ruler and one of history’s earliest examples of a sovereign who governed by moral conviction rather than force. After his conversion to Buddhism, Ashoka propagated the teachings of Buddha across Asia and beyond through edicts, stupas, and missionary efforts. It is from this period that the Ashokan Lion Capital and the Dharma Chakra were adopted into the official iconography of India.

Indeed, the Ashoka Chakra—with its 24 spokes symbolising righteous action and universal moral order—now adorns the centre of the Indian National Flag, and the Ashokan Emblem has been enshrined as the official emblem of the Republic of India. These are not mere decorative artefacts—they represent a conscious embrace of Buddha’s values into the modern Indian national psyche and constitutional identity.

The influence of Buddha’s egalitarian ethos extended far beyond symbolism. The values of equity, equality, fraternity, and social justice—enshrined in the Preamble and core articles of the Indian Constitution—bear unmistakable traces of Buddhist moral philosophy. This resonance is especially evident in the life and thought of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the principal architect of the Indian Constitution. A lifelong admirer of Buddha's teachings and their rejection of caste hierarchy, Ambedkar embedded these humanist values into the very fabric of the Indian Republic.

Although Dr. Ambedkar did not formally convert to Buddhism until October 14, 1956, just two months before his passing, and well after the Constitution had been adopted in 1950 and his resignation as Law Minister in 1951, the intellectual and ethical framework he brought to the Constituent Assembly was deeply inspired by Buddhist ideals. For him, the Dhamma was not merely a religious path but a radical instrument of social transformation—precisely the kind of foundation he envisioned for an independent, democratic, and just India.

Buddha Invented Communism? Introduction

The assertion that "Buddha Invented Communism" might strike many as anachronistic or even sacrilegious. Yet, a closer examination of the principles and practices initiated by Siddhartha Gautama and the ideologies underpinning communism reveals intriguing parallels. This succinct essay seeks not to conflate Buddhism with communism but to provoke thought on the similarities between Buddha's teachings and communist doctrines. The aim is to understand how both sought to challenge entrenched hierarchies, propose egalitarian ideals, and reimagine human relations beyond the material.

1.) Renunciation of Wealth

Buddha famously renounced his princely riches and luxurious life in search of enlightenment, preaching detachment from material wealth as a path to spiritual liberation. This fundamental tenet mirrors the communist critique of wealth accumulation and capitalist excess, advocating for a society where wealth does not dictate one's value or power. Buddha’s rejection of caste-based privilege and economic inequality echoes in modern critiques of class divisions and exploitative systems that communism sought to dismantle.

2.) Sanghas as Communes

The establishment of Sanghas by Buddha, communities where monks live and practise together, can be likened to communist "communes." These Sanghas operated on principles of collective living and mutual support, with lay followers encouraged to support these communities through donations and bequests, embodying a form of economic redistribution. Sanghas promoted simplicity, cooperation, and the idea that no one should hoard more than necessary—values that resonate deeply with Marxist visions of shared resources and collective well-being.

3.) Centralised Authority

In the Sangha, Buddha's word was paramount, akin to the General Secretary of the Communist Party whose directives are undisputed. This centralisation of authority under a single figure or ideology is a common feature in both systems, guiding the moral and practical life of the community. In both cases, this authority was not merely administrative but deeply philosophical—anchored in a belief system that promised liberation, whether from suffering or exploitation.

4.) Ambivalence Towards Deities

Buddhism emphasises personal enlightenment over deity worship, aligning with communism's secular focus. Both prioritise human agency in achieving societal or spiritual goals, with communism under Lenin and Stalin advocating state atheism to consolidate ideological authority. This parallel showcases a shared emphasis on self-reliance and rationalism in shaping human destiny. The Buddha’s silence on metaphysical speculation mirrors communism’s materialist stance, redirecting focus from the divine to the human condition.

5.) Supremacy of the Dhamma

Just as the Communist Manifesto is held as the ideological blueprint for a communist society, Buddha's Dhamma serves as the ultimate guide for achieving enlightenment and liberation from suffering. Both texts provide a comprehensive worldview and a path forward for adherents. They are not passive readings but active blueprints—meant to reshape minds, institutions, and collective futures with unwavering commitment.

6.) Absence of Democracy

Neither early Buddhist Sanghas nor communist regimes emphasised democratic decision-making, often favouring a hierarchical or centralised model of governance. This approach reflects a belief in the infallibility of the enlightened or ideologically pure leader(s). In both, the authority of the doctrine or leader was viewed as superior to the will of the majority—a trade-off between moral clarity and democratic consultation.

7.) State Religion and Ideology

Emperor Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism effectively made it a state religion in ancient India, similar to how communist ideologies became the sole political doctrine in countries like the Soviet Union. This state endorsement propelled the spread and institutional support for each system. Ashoka’s patronage allowed Buddhism to flourish beyond India, just as state machinery helped communism expand across continents—both proving that ideas, when coupled with power, can transcend borders.

8.) Military Defence

Buddhism initially lacked formal defence mechanisms for its monasteries, unlike the militarised approaches of communist states. Yet, the existence of Japan's warrior monks (sohei) illustrates that Buddhism was not entirely passive against external threats, reflecting complexities similar to those in the defence policies of communist states. The Buddhist commitment to non-violence was challenged in turbulent times, much as communist regimes justified militarisation as a means to protect revolution and ideology. The absence of a defence strategy may have played a role in Buddhism's decline in its birthplace, while the Soviet Union's collapse was partly due to excessive military expenditure.

9.) Idolisation and Legacy

Despite Buddha's stance against idol worship, his statues and images proliferate worldwide. Similarly, figures like Lenin and Mao remain revered icons in countries that have moved towards market economies, symbolising the enduring power of ideology beyond the lives of its founders. The idols survive, while their ideals have been quietly buried. In both traditions, iconography became a tool of memory, reverence, and at times, political propaganda—underscoring the paradox between doctrine and devotion.

Ideologies in Exile: From Bodh Gaya to Berlin and Beyond

One of the most intriguing parallels between Buddhism and communism lies in the trajectory of their global influence. Both systems of thought, though born in specific cultural and political settings, spread far beyond their geographic origins. Buddhism, while rooted in ancient India, flourished across East and Southeast Asia, becoming deeply entrenched in countries like Sri Lanka, China, Japan, Thailand, and Myanmar. Ironically, its presence in India—the land of its birth—diminished significantly over the centuries, even as its influence reshaped civilisations abroad.

The story of communism follows a similar arc. Though its theoretical foundations were laid by Karl Marx, a German philosopher and economist, communism never found deep roots in Germany itself. Marx wrote his magnum opus, Das Kapital, while in exile in London in 1867, far from his native Rhineland and his ideology never found favour in the UK. The practical and revolutionary expressions of communism would instead take shape in Russia, China, Cuba, Vietnam, and elsewhere. In both cases, the motherlands of the ideology became marginal, even resistant, to the doctrines they birthed—while distant lands adopted, adapted, and sometimes even transformed those visions into formidable sociopolitical forces.

Summing Up

While the analogy between Buddha's teachings and communism may not align perfectly, the comparison invites a deeper reflection on how ideologies shape societies. Both Buddhism and communism sought in their ways to redefine the relationship between individuals, their societies, and the material world. Each questioned the status quo—be it through renunciation or revolution—and sought liberation from deeply entrenched suffering, whether spiritual or socio-economic.

And today, as we mark Bodh Poornima, the full moon night that commemorates the enlightenment of the Buddha, let us renew our quest for truth, equity, and inner liberation—not through dogma or political absolutism, but through compassionate inquiry and fearless dialogue. In remembering the Buddha’s light on this sacred night, we are reminded that ideas endure beyond empires, and that peace—like revolution—begins within.