Baba Sri Chand Ji, Baba Gurditta Ji, and the Evolution of Sikhism: A Historical Perspective

The Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925, provides a clear definition of Sikh identity but does not prevent Sikhs from acknowledging the role of historical figures like Baba Sri Chand Ji and Baba Gurditta Ji.

Baba Sri Chand Ji, Baba Gurditta Ji: A Historical Perspective

1. Introduction: The Legacy of Guru Nanak’s Eldest Son

Baba Sri Chand Ji, the eldest son of Guru Nanak Dev Ji, holds a unique and complex place in Sikh history. His ascetic path, his reverence for Guru Nanak, and his role in preserving Sikh teachings through the Udasi tradition are often viewed through varying lenses. His relationship with the Sikh Gurus and the evolution of his order have shaped the broader understanding of Sikh identity.

2. Baba Sri Chand Ji’s Spiritual Connection to Guru Nanak

Bani as Evidence of Devotion

Baba Sri Chand Ji’s compositions, particularly Aartha Sahib and Guru Nanak Sahansar Nama, explicitly venerate Guru Nanak Dev Ji. He writes, “I bow again and again at the feet of Siri Guru Nanak”, demonstrating his deep reverence. While he pursued an ascetic path, the Udasi tradition he founded played a significant role in spreading Guru Nanak’s teachings across India.

Divergent Paths, Shared Values

Despite his choice of celibacy and renunciation, which contrasted with Guru Nanak’s emphasis on the householder’s life (gristi jeevan), Baba Sri Chand Ji upheld the core Sikh values of meditation (Naam Simran), service (seva), and inclusivity. His role in disseminating Sikh teachings ensured that the nascent Sikh faith gained a wider audience beyond Punjab.

3. Historical Accounts of Respect from Sikh Gurus

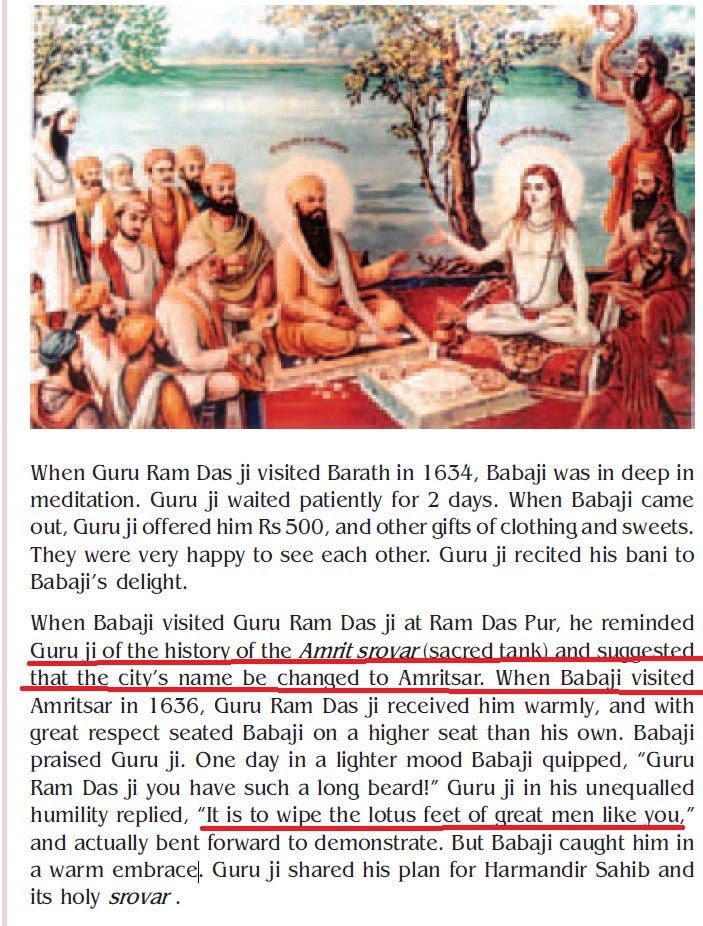

Guru Ram Das Ji and the Test of Humility

One of the most well-known encounters between a Sikh Guru and Baba Sri Chand Ji occurred when he met Guru Ram Das Ji, the fourth Sikh Guru. When Baba Sri Chand questioned the length of the Guru’s beard, Guru Ram Das Ji humbly replied that it was meant to wipe the feet of saints like him. This act of humility moved Baba Sri Chand Ji to acknowledge Guru Ram Das’s spiritual eminence.

Guru Arjan Dev Ji and the Preservation of Sikh Scriptures

Guru Arjan Dev Ji, the fifth Sikh Guru, approached Baba Sri Chand Ji for assistance in compiling Guru Nanak’s compositions. Baba Sri Chand Ji readily provided access to these invaluable writings, ensuring their inclusion in the Adi Granth. His direct contribution toa verse in Sukhmani Sahib further emphasizes his role in Sikh theological history.

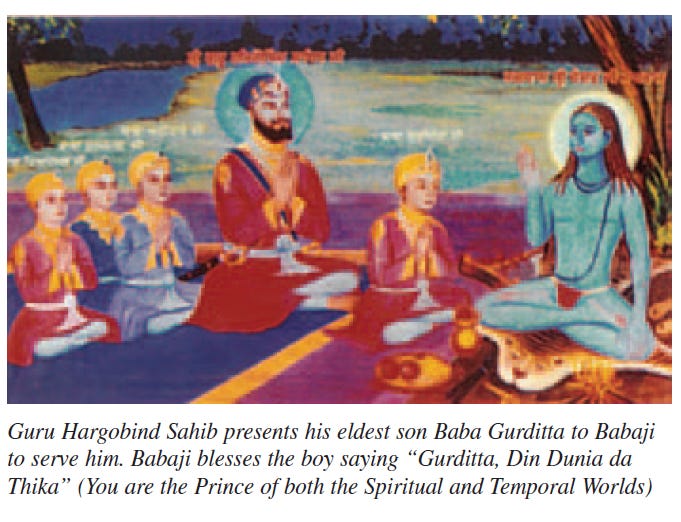

Guru Hargobind Ji and the Udasi Succession

The relationship between Baba Sri Chand Ji and Guru Hargobind Sahib Ji was particularly profound. Guru Hargobind Sahib Ji’s eldest son, Baba Gurditta Ji, was chosen to succeed Baba Sri Chand Ji as the head of the Udasi order. This decision underscored the Sikh Gurus’ recognition of the Udasi sect as an important missionary arm of Sikhism.

4. Reconciling Historical Contradictions

Early Tensions and Later Reconciliation

After Guru Nanak’s passing, Baba Sri Chand Ji and his younger brother Lakhmi Das initially contested Guru Angad Dev Ji’s succession, citing ancestral rights to Kartarpur. However, over time, Baba Sri Chand Ji and the later Sikh Gurus bridged this divide, reinforcing their mutual respect and spiritual continuity.

Fact vs. Fiction: Addressing Misconceptions

Some historical accounts downplay Baba Sri Chand Ji’s role in Sikhism, painting him as an outsider. However, numerous sources indicate that the Sikh Gurus not only respected him but also sought his wisdom in preserving Guru Nanak’s teachings. The Udasi sect, while evolving differently over time, played a critical role in spreading Sikhism across the subcontinent.

5. Baba Gurditta Ji and the Udasi Order

Leadership and Expansion of the Udasi Sect

Baba Gurditta Ji was formally initiated as the successor of Baba Sri Chand Ji, marking a significant step in integrating the Udasis with mainstream Sikhism. He established four major preaching centers (dhūāṅs), which helped in spreading Sikh teachings far and wide. His leadership ensured that the Udasis remained aligned with Guru Nanak’s philosophy, even as they retained elements of asceticism.

Householder Life and Sikh Norms

Unlike most Udasi leaders who embraced celibacy, Baba Gurditta Ji led a married life. He married Mata Nihal Kaur Ji and fathered Guru Har Rai Ji, the seventh Sikh Guru. His marriage posed an apparent contradiction with Udasi ideals, yet it was a strategic reconciliation between ascetic and householder traditions, reinforcing the Gurus’ pragmatic approach to leadership.

Addressing Doctrinal Differences

Baba Gurditta Ji’s appointment as Udasi head while maintaining a householder’s life challenges rigid notions of asceticism. This phase of Sikh history saw the Udasis functioning as missionaries who complemented mainstream Sikh efforts without conflicting with the core values of the Sikh Gurus.

6. The Singh Sabha Movement and Its Impact on Udasi Influence

The 19th-century Singh Sabha Movement sought to standardize Sikh practices and revive Sikh identity in response to colonial-era distortions. While the movement was crucial in eliminating Hindu influences from Sikh institutions, it also led to the marginalization of sects like the Udasis, who had historically been caretakers of gurdwaras.

Standardization of Sikh Identity

The Singh Sabha emphasized the Khalsa identity, reinforcing the Five Ks (kesh, kara, kachera, kirpan, kangha). This strict delineation led to the progressive exclusion of groups like the Udasis, who did not fully conform to the Khalsa discipline.

Gurdwara Reform Movement and the End of Udasi Control

The passage of the Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925 transferred gurdwara management from Udasi mahants to elected Sikh committees under the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC). This marked a significant institutional shift, ensuring that Sikh places of worship adhered to established Sikh norms.

7. The Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925: Defining a Sikh

Legal Definition of a Sikh: The Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925

The Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925, was enacted to provide a legal framework for the management and administration of Sikh gurdwaras. One of its key provisions was the definition of a Sikh, which was necessary to ensure clarity in matters concerning Sikh religious institutions. The definition is provided in Section 2(9) of the Act, as follows:

“Sikh” means a person who professes the Sikh religion or, in the case of a deceased person, who professed the Sikh religion or was known to be a Sikh during his lifetime.”

Additionally, the Act addresses situations where a person’s Sikh identity may be questioned. In such cases, a living individual is deemed to be a Sikh if they make the following formal declaration:

“I solemnly affirm that I am a Sikh, that I believe in the Guru Granth Sahib, that I believe in the Ten Gurus, and that I have no other religion.”

This definition highlights three essential aspects of Sikh identity:

Profession of the Sikh religion – An individual must self-identify as a Sikh.

Belief in Guru Granth Sahib Ji – Recognizing Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji as the eternal Guru.

Belief in the Ten Gurus – Acknowledging the spiritual lineage from Guru Nanak Dev Ji to Guru Gobind Singh Ji.

The declaration requirement ensures that Sikh identity is grounded in both faith and self-affirmation, particularly in legal and administrative matters concerning gurdwara governance. While the Act provides a precise criterion for Sikh identity, it does not prohibit Sikhs from honouring revered historical figures such as Baba Sri Chand Ji and Baba Gurditta Ji. Their contributions to the preservation and propagation of Sikhism remain undeniable; however, the ultimate spiritual authority and the eternal embodiment of the living Guru in Sikhism are solely vested in Guru Granth Sahib Ji, as ordained by Guru Gobind Singh Ji.

Implications of the Definition

This definition served to distinguish Sikh identity from Hinduism and other religious traditions. While it does not explicitly prohibit Sikhs from respecting revered historical figures like Baba Sri Chand Ji or Baba Gurditta Ji, it firmly establishes Guru Granth Sahib Ji as the sole spiritual authority, as discussed above.

Reverence vs. Worship

Sikhism, rooted in monotheism and Guru Nanak’s teachings, allows for reverence of historical figures without elevating them to a divine status. Baba Sri Chand Ji and Baba Gurditta Ji are deeply respected by many Sikhs for their contributions to the Sikh faith, but they are not worshiped as living Gurus. Their role in preserving and propagating Sikhism is immense, and their legacy remains an integral part of Sikh history.

8. Summing Up: A Legacy of Coexistence

The relationship between Baba Sri Chand Ji, Baba Gurditta Ji, and the Sikh Gurus reflects the early diversity within Sikhism. While the Udasis later evolved in ways that distanced them from mainstream Sikh practice, their foundational contributions to Sikh history are undeniable. The balance between asceticism and the householder’s life, the preservation of Guru Nanak’s bani, and the missionary expansion of Sikhism all owe much to these revered figures.

The Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925, provides a clear definition of Sikh identity but does not prevent Sikhs from acknowledging the role of historical figures like Baba Sri Chand Ji and Baba Gurditta Ji. Their contributions to the faith, while distinct, remain vital in the grand tapestry of Sikh history.

Citations

(Click on the links to access the sources)

[1] Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925

[2] Baba Sri Chand’s Contributions

[3] Baba Gurditta and Udasi Order

[4] Singh Sabha Movement

[5] History of Sikhism