100 Years of the 'Jaito Da Morcha'

A significant chapter in the peaceful efforts of Sikhs to secure the right to manage their historical gurdwaras autonomously.

100 Years of the 'Jaito Da Morcha'

As we mark the centenary of the historic 'Jaito Da Morcha' today—coinciding with the centennial of the indiscriminate firing by British troops on unarmed Sikh Jathas exactly one hundred years ago—it is essential to reflect on and honour the bravery, resilience, and steadfast dedication of the Sikh community to their rights and religious freedom. This pivotal chapter in India's freedom struggle highlights the unparalleled contributions of the Sikh community to the national movement against colonial oppression, underscoring their pursuit of justice and the inalienable right to manage their sacred gurdwaras through a democratically elected body of their own.

The Catalyst: Abdication of Maharaja Ripudaman Singh

The agitation was sparked on July 9, 1923, by the forced abdication of Maharaja Ripudaman Singh of Nabha, a progressive and popular ruler from the Phulkian misl of the Sidhu-Brar clan. Known for his candid stance on Sikh issues and his unequivocal, open support for the Akali Dal and the Gurdwara Reform Movement, his ouster by the British Government ignited unrest among Sikhs, who perceived this as an infringement on their rights and sovereignty. This incident infused new energy into the movement led by the Akali Dal, which was being coordinated from Amritsar.

Gurdwara Reform Movement and SGPC's Role

During the Gurdwara Reform Movement (1920-1925), which sought to free Sikh gurdwaras from British-backed mahants (priests)—many of whom were morally and financially corrupt—the SGPC, initially a non-statutory body, played a pivotal role. This movement was not merely a battle for control over religious sites but also a wider struggle for the Sikh community's identity and rights. The SGPC, as their own democratically elected body, along with the political entity, the Akali Dal, articulated this fight against colonial dominance.

The Prelude to the Turning Point

In the buildup to a significant turning point, an Akhand Path (a 48-hour continuous recitation of the entire Sri Guru Granth Sahib) was initiated at Gurdwara Gangsar Sahib in Jaito, located within the Princely State of Nabha and overseen by a British-appointed administrator, specifically to pray for the reinstatement of Maharaja Ripudaman Singh. The arrest of Sikh priests by colonial authorities, in an attempt to disrupt this revered spiritual ceremony, only fortified the Sikh community's determination. In a defiant response, an indefinite Akhand Path was initiated, receiving backing from the SGPC, which at the time did not yet enjoy official legal status. The situation intensified when colonial officials disrupted the ceremony by removing the holy “beed” of Sri Guru Granth Sahb. They forcibly ended the Akhand Path on September 14, 1923, and seized control of the gurdwara. As a countermeasure, the SGPC started dispatching small contingents of 25 Sikhs from Amritsar to peacefully enter the gurdwara, though these efforts were met with arrest and aggression, further highlighting the escalating tensions. Such was the response of the Sikh Sangat that the size of the jatha had soon to increased to 500 persons daily.

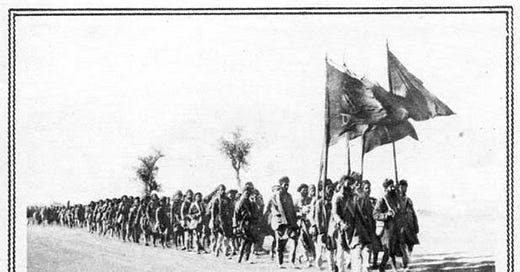

The Flash Point: Firing of February 21, 1924

The peaceful march towards Gurdwara Gangsar Sahib on February 21, 1924, became a watershed moment in the struggle. Ordered by the Nabha State administrator, British forces opened fire on unarmed Sikh protesters, leading to more than 150 deaths and 300 injuries, an act that drew widespread condemnation and bolstered support for the Sikh cause both nationally and internationally. The escalation culminated with a 500-member jatha being attacked by British forces, a brutal act that underscored the colonial regime's ruthlessness and marked a significant turning point in the movement for Sikh rights and sovereignty.

Jawaharlal Nehru and National Leaders' Involvement

The agitation caught the attention of national figures like Jawaharlal Nehru, whose imprisonment in Nabha jail for participating in the protests highlighted the movement's significance in the broader struggle for Indian independence. Despite being denied legal rights, Nehru's involvement underscored the interconnectedness of the Sikh struggle with the national freedom movement.

Mahatma Gandhi's Call and Support

At the urging of Mahatma Gandhi, the Congress had already passed a resolution on February 1, 1924, calling upon Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and Parsis to stand in solidarity with the Sikhs in their agitation against the British. Although specific statements from Mahatma Gandhi directly addressing the Jaito Da Morcha are not extensively documented, his steadfast commitment to non-violent resistance and the promotion of religious and civil liberties aligned closely with the spirit of the Sikh movement. Gandhi's advocacy for peaceful protest found a strong echo in the Sikh community's method of pursuing their cause.

SGPC: A Statutory Body

The relentless efforts of the Sikhs led to the formal recognition of the SGPC as a statutory body in 1925, through the Sikh Gurdwaras Act. This was a monumental achievement, granting the Sikh community the right to manage their gurdwaras democratically, without discrimination based on caste or gender—a testament to their commitment to equality and justice. The SGPC continues till date the inter-state statutory body to manage the sacred Sikh shrines and Gurdwaras within Punjab, UT Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh and till recently, Haryana. The contentious issue of nearly 70 lakh “Sehajdhari” Sikhs allegedly disenfranchised through an amendment to the Act, currently facing legal scrutiny, however, continues to stir debate among the Sikh community, which widely regards their faith as embracing inclusivity.

Legacy, Lessons and Reflection

The 'Jaito Da Morcha' transcends its historical confines, embodying the Sikh community's peaceful yet resolute stand against oppression. It highlights their readiness to sacrifice for deeply held beliefs, underscoring their vital contribution to India's independence movement.

Reflecting on the century since this critical juncture, it is crucial to acknowledge the Sikh community's persistent spirit in championing their rights and enriching India's diverse and pluralistic fabric. The 'Jaito Da Morcha' serves as a poignant reminder of the power of unity, peaceful resistance, and an unwavering quest for justice. As the agitating Punjab Farmers prepare for their “Delhi Chalo” march today, 100 years later, this moment in history resonates, emphasizing that the legitimate demands of the farming community should be met with empathy, dialogue, and compromise, not with barricades, barbed wire, and rubber bullets.

Your illuminating long post presses me to share the following portion from my book "Instant History: A Memoir (Bloomsbury 2021). It may be of interest to you.

Jaito Then, Jaito Now

One early October day in 1988, PM Rajiv Gandhi visited terrorism-infested Punjab and addressed three public meetings. With modest audiences of a few thousand people, there were no cheers and no clapping.

What greeted him instead was an unnerving silence, and that summed up the response of the people of the state—indifference and scepticism.

The rather bland and unimaginative fare that Rajiv dished out had failed to enthuse people at the public meetings at Goindwal in Amritsar district, Jaito in Faridkot district and Jalandhar. People had been ferried from other places after elaborate security checks to make up the audiences as Punjab

was reeling under violence. I was covering Jaito while my colleagues were covering Goindwal and Jalandhar. As usual, the public relations (PR) department took the press party from Chandigarh to Jaito in a cavalcade of cars. Packed breakfast from a reputed restaurant was served while travelling. The PR team had also put together a bunch of cyclostyled papers from a relevant book about the historical Jaito Morcha of 1923.

Rajiv Gandhi offered the same package to Punjab in all three meetings. The same speech was repeated everywhere. There was elaborate bandobust for the press at the Central Telegraph Office of the nearby

town Bathinda. Cups of steaming coffee were being served. Typewriters were lined up, and the teleprinter operators were waiting to transmit copies. We reported the speech. Inputs from all three places were summed up by newspapers to make a single comprehensive news item. But the Statesman stole the show. Its young

reporter Sanjeev Miglani filed an altogether different story. He compared Rajiv Gandhi’s Jaito visit to the visit of Jawahar Lal Nehru and other freedom fighters on 21 September 1923 to take part in the morcha of the gurdwara reforms movement. Jaito was the part of Nabha State, ruled by a feudal lord. The entire population had, with unprecedented enthusiasm, thronged the venue of the morcha in 1923. This time,

however, an undeclared curfew had forced residents of the town to remain confined to their houses. The town bore a deserted look. As mentioned earlier, the audience comprised people ferried from other places

in trucks and buses. He merely compared the two moods of the people. It was a hit. Despite having the relevant material, I failed to use it to make the news more interesting.

Bitter truth narrated with courage and wisdom 👍👍